Cognitive Impairment Precedes and Predicts Functional Impairment in Mild Alzheimer’s Disease

Abstract

Background: The temporal relationship of cognitive deficit and functional impairment in Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is not well characterized. Recent analyses suggest cognitive decline predicts subsequent functional decline throughout AD progression.

Objective: To better understand the relationship between cognitive and functional decline in mild AD using autoregressive cross-lagged (ARCL) panel analyses in several clinical trials.

Methods: Data included placebo patients with mild AD pooled from two multicenter, double-blind, Phase 3 solanezumab (EXPEDITION/2) or semagacestat (IDENTITY/2) studies, and from AD patients participating in the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI). Cognitive and functional outcomes were assessed using AD Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog), AD Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living instrumental subscale (ADCS-iADL), or Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ), respectively. ARCL panel analyses evaluated relationships between cognitive and functional impairment over time.

Results: In EXPEDITION, ARCL panel analyses demonstrated cognitive scores significantly predicted future functional impairment at 5 of 6 time points, while functional scores predicted subsequent cognitive scores in only 1 of 6 time points. Data from IDENTITY and ADNI programs yielded consistent results whereby cognition predicted subsequent function, but not vice-versa.

Conclusions: Analyses from three databases indicated cognitive decline precedes and predicts subsequent functional decline in mild AD dementia, consistent with previously proposed hypotheses, and corroborate recent publications using similar methodologies. Cognitive impairment may be used as a predictor of future functional impairment in mild AD dementia and can be considered a critical target for prevention strategies to limit future functional decline in the dementia process.

INTRODUCTION

Clinical trials of potential treatments for Alzheimer’s disease (AD) currently require co-primary endpoints of cognition and function or global clinical status to be assessed independently to satisfy regulatory requirements. Longitudinal studies of persons at risk for AD have demonstrated the initial clinical presentation of AD is one in which there are cognitive deficits measurable with performance-based tests, but with no evident loss of activities of daily living. This initial state is frequently referred to as mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or prodromal AD [1, 2]. The earliest functional deficits, as patients advance to mild dementia, are often difficult to characterize [3]. To enable more informative studies in MCI and mild AD dementia, a better understanding of the relationship between cognitive and functional progression in milder stages of dementia due to AD is needed.

Recent evidence has suggested that AD is a continuum, with the clinical symptoms of overt dementia becoming apparent a decade or more after the biomarker-associated pathophysiological process begins in sporadic AD [4–9] and autosomal dominant AD [10]. Biomarker studies investigating the early stages of neurodegeneration have postulated that, following pathophysiological changes, cognitive impairment occurs first followed by functional impairment [11]. Based on this biomarker evidence of AD pathology, recent academic workgroups have established new diagnostic criteria to span the AD continuum [1, 4, 12, 13].

The early stages of AD, from preclinical to MCI, are defined clinically by the level of cognitive impairment alone [1], as functional deficits are not apparent until later in the disease process. Consequently, demonstrating the benefits of disease-modifying treatments on function in patients in early stages of the disease is inherently difficult. There have been limited publications showing functional effects in mild AD patients. Few studies involving symptomatic drugs approved for mild to severe AD dementia patients temporarily showed improved cognition and stabilization of function with limited or no improvement above baseline in mild AD. One study by Potkin and colleagues (2002) supported the hypothesis that functional impairment differs across the AD continuum, and that treatment with rivastigmine, a cholinesterase inhibitor, produced modest improvement in function across all disease stages; however, the effects were dependent on level of impairment and frequency of functional activity [14]. In mild-moderate AD dementia populations, currently approved symptomatic treatments including rivastigmine, galantamine, memantine, and donepezil improve cognition and generally may preserve function only over longer periods [15–19].

Auto-regressive cross-lagged (ARCL) panel analysis is a classical structural equation model used to simultaneously analyze multiple outcomes that are measured repeatedly over time. It is designed to assess the strength of potential reciprocal causal relationships between the outcomes and explore inference of influence of one variable over another [20, 21]. Previous studies have used this model to investigate the temporal order and causal relationship between nicotine dependence and average smoking [22] and cognitive-behavioral interventions and chronic pain [23].

While few empirical data have been reported, a recent publication by Zahodne and colleagues (2013) explored the relationship between cognition and function using ARCL panel analysis in two longitudinal studies with non-demented and demented older adults [24]. The two studies included were the population-based Washington Heights/Hamilton Heights Inwood Columbia Aging Project (WHICAP) with non-demented older adults and the clinical trial Predictors Study with patients with probable AD dementia, which measured cognitive and functional abilities for 18 to 24 months and over 6 years, respectively. In these studies, cognitive impairment more consistently predicted subsequent functional impairment in non-demented older adults, a subset who eventually developed dementia, and in patients with prevalent AD. The authors stated these data support the theory that functional impairment may be a direct result of cognitive impairment [24].

The objective of this post-hoc analysis was to better understand the temporal relationship between cognitive and functional decline in mild AD dementia. Our previous publication found that cognitive impairment is more evident than functional impairment in mild AD dementia [25]. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that cognitive decline is the core symptom of AD and that functional impairment is primarily caused by and follows cognitive decline in the natural course of the disease progression. This post-hoc analysis explores this hypothesis more directly by utilizing ARCL analyses to investigate the potential reciprocal causal-effect between cognitive impairment and functional impairment and compares the relative strength of the two directions.

We hypothesize that the ARCL panel analyses will demonstrate that cognitive decline precedes and predicts functional decline during the natural disease progression of mild AD dementia, while the reciprocal direction is not supported.

METHODS

EXPEDITION program

EXPEDITION and EXPEDITION2 were two multicenter, double-blind, Phase 3 studies of solanezumab. Pooled placebo patients with mild AD dementia (Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] score 20 to 26, n = 663), were included in this post-hoc analysis. Solanezumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody designed to clear soluble amyloid-β (Aβ) from the brain, was studied as a potential disease-modifying agent for the treatment of AD, and the primary outcomes of the trials (EXPEDITION and EXPEDITION2) have been reported previously [26]. All patients provided informed consent before participation in the EXPEDITION study program, and the study protocols were approved by ethical review boards. Patient demographics are shown in Table 1.

Cognitive and functional outcome measures were assessed at baseline and at 6 post-baseline time points every 3 months for 18 months in the EXPEDITION studies. Cognitive ability was assessed using the 14-item AD Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog14) with a score range of 0 to 90 (with higher scores indicating greater disability) [27]. Function was measured with the AD Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living Scale instrumental subscale (ADCS-iADL), comprised of items 7 through 23 of the ADCS-ADL scale, with scores from 0 to 56 (lower score denoting greater functional loss).

IDENTITY program

A similar clinical trial dataset of pooled placebo-treated, mild AD dementia patients (MMSE score 20 to 26) from two multicenter, double-blind, Phase 3 semagacestat studies (IDENTITY and IDENTITY2, n = 629) was also included in the analyses. Semagacestat, a γ-secretase inhibitor, was studied as another putative disease-modifying agent for the treatment of AD. Treatment in both studies was terminated prematurely based on data that showed cognitive worsening in patients treated with semagacestat compared to placebo. Patients were then followed up for seven months to collect additional safety data. The results from the IDENTITY studies have been reported previously [28]. All patients provided informed consent before participation in the IDENTITY study program, and the study protocols were approved by ethical review boards. Additional patient demographics are included in Table 1.

Cognitive and functional outcome measures were the same as those of the EXPEDITION study program and were collected at baseline and at 6 post-baseline time points every 3 months for 18 months.

ADNI

A third dataset included mild AD patients from the AD Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (MMSE score 20 to 26, n = 336) [29]. Additional patient demographics are included in Table 1. ADNI is a natural history, longitudinal, non-treatment study that was launched in 2003 by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB), the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), private pharmaceutical companies, and non-profit organizations as a $60-million, 5-year public/private partnership. ADNI is structured like a clinical trial but does not provide an intervention. For up-to-date information, see http://www.adni-info.org.

Cognitive and functional outcome measures in ADNI included time points at baseline and after 6, 12, and 24 months. In the ADNI dataset, cognition was evaluated with the 11-item ADAS-Cognitive subscale (ADAS-Cog11) with score range of 0 to 70 [27, 30] and function was measured with the Functional Activities Questionnaire (FAQ) [31] with scores ranging from 0 to 30 (higher score representing more impairment).

Statistical analyses

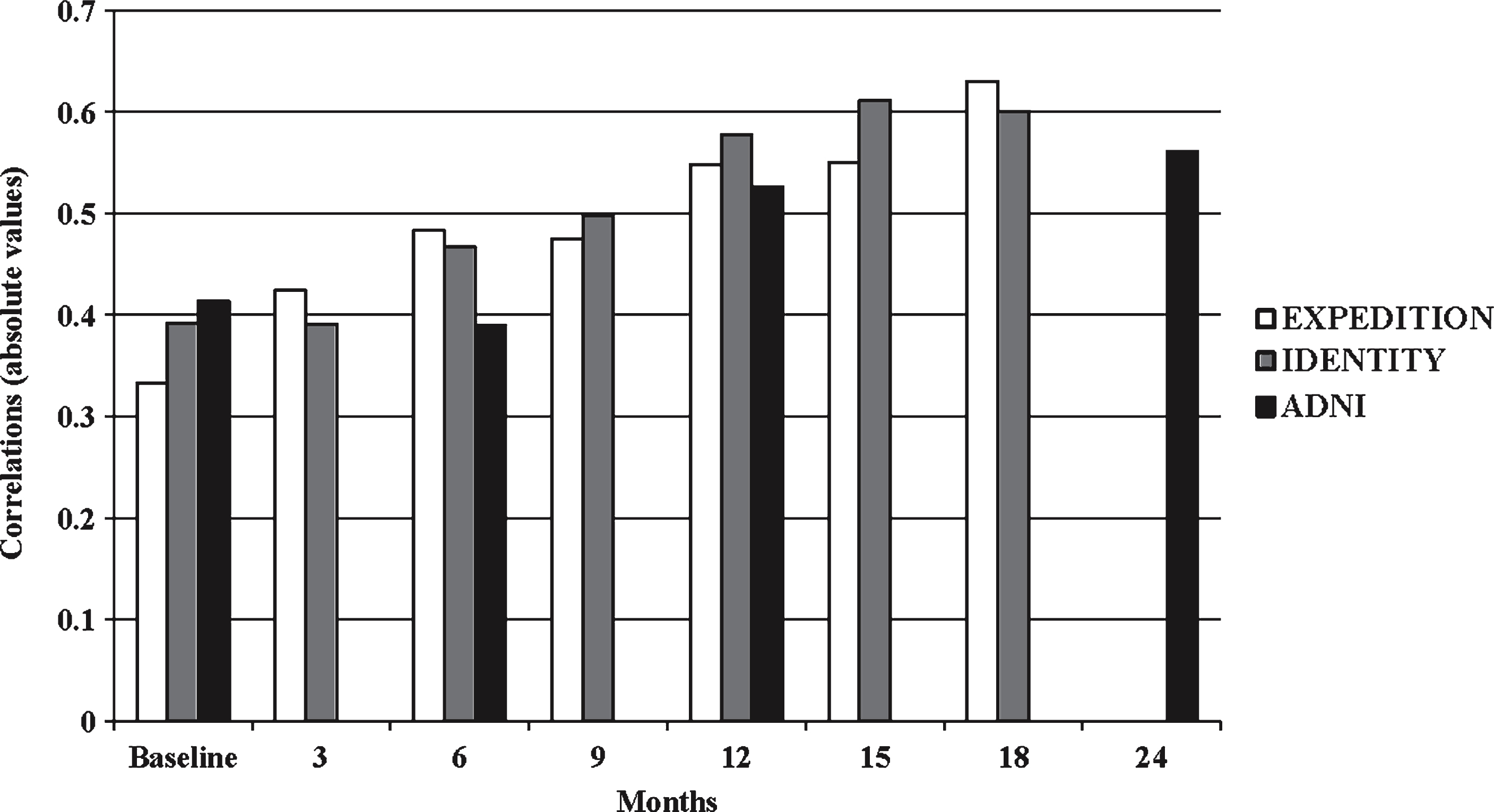

Mean scores with standard deviations for each visit on both cognitive and functional measures are shown in Table 2. Spearman rank correlations between the absolute values of cognitive and functional outcome measures at baseline and for each post-baseline visit were determined for each dataset.

ARCL panel analyses were used to evaluate the structural relationships between cognitive and functional impairment based on the longitudinal data over the course of the studies. In the ARCL model, the interrelationship between cognitive performance and functional abilities are evaluated based on the estimates of the autoregressive coefficients from time (t-1) to time (t), β, as well as the cross-lagged regression coefficients from time (t-1) to time (t), γ. The correlation between the two outcome variables, ρ, was also estimated [22] (Fig. 1). Full Information Maximum Likelihood estimation was used to make use of all available data from all patients.

The overall model fit was determined using three standard measures, including the comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root mean square residual (SRMR) [21]. A model was considered acceptable with values of RMSEA <0.08, SRMR <0.05, and CFI >0.95 [24]. All analyses were performed using SAS9.2.

RESULTS

EXPEDITION program

In the EXPEDITION study program, the Spearman rank correlation between ADAS-Cog14 and ADCS-iADL was 0.333 at baseline and increased to 0.630 after 18 months (Fig. 2). The ARCL panel analysis model fit statistics for the EXPEDITION study program were, RMSEA = 0.04 with a 90% confidence interval of (0.03, 0.05), SRMR = 0.06, and CFI = 0.99 (Table 3). Results demonstrated cognitive impairment significantly predicts future functional impairment in 5 of 6 time points (all time points except 6 month predicting 9 month). Functional scores predicted cognitive outcome in only 1 of 6 time points (6 month predicting 9 month) when the same analyses were performed to test the reverse hypothesis. The magnitude of cross-lagged coefficients was, in general, greater for cognition predicting subsequent function than for function predicting cognition (Table 4). The direction of the cross-lagged regression coefficient indicates that a more impaired cognitive score predicts a more impaired functional score at subsequentvisits.

IDENTITY program

In the IDENTITY study program, the Spearman rank correlation between ADAS-Cog14 and ADCS-iADL was 0.392 at baseline and increased to 0.600 at 18 months (Fig. 2).

The model fit statistics were RMSEA = 0.07 with a 90% confidence interval of (0.06, 0.09), SRMR = 0.05, and CFI = 0.98 for the IDENTITY study program (Table 3). The cross-lagged regression coefficients were significant for cognition predicting function for 3 of 6 time points (3 month predicting 6 month, 6 month predicting 9 month, and 9 month predicting 12 month), but not at any time points for function predicting cognition (Table 4). Similar to the EXPEDITION study program results, in general, there was a stronger cross-lagged coefficient for cognition predicting subsequent function than vice versa (Table 4). Also analogous to the EXPEDITION results, the direction of the cross-lagged regression coefficient indicates that a more impaired cognitive score predicts a more impaired functional score at the subsequent visit.

ADNI

In the ADNI dataset, the Spearman rank correlation between ADAS-Cog11 and FAQ was 0.414 at baseline. By the end of the 24-month study, the correlation increased to 0.561 (Fig. 2).

The model fit statistics for ADNI were RMSEA =0.08 with a 90% confidence interval of (0.03, 0.12), SRMR = 0.02 and CFI = 0.99 (Table 3). The cross-lagged regression coefficients based on ADNI data were significant for cognition predicting function at one time point (12 month predicting 24 month), but not at any of the time points for function predicting cognition (Table 4). The direction of the cross-lagged coefficients was opposite from those for the EXPEDITION and IDENTITY programs, because higher scores on the FAQ indicate worsened function while lower scores indicate worsened function for the ADCS-ADL. Therefore, the ADNI data, like the EXPEDITION and IDENTITY data, indicates that a more impaired cognitive score predicts a more impaired functional score at the subsequent visit.

Similar results were observed in all three databases when only completers were included in the cross-lagged analyses.

DISCUSSION

This post-hoc analysis evaluated the temporal relationship between cognitive and functional impairment during natural disease progression without investigational treatment interventions in mild AD patients using auto-regressive cross-lagged panel analyses. Results from three independent datasets (EXPEDITION, IDENTITY, and ADNI) demonstrated that cognitive impairment preceded and predicted subsequent functional decline in mild AD dementia, but functional impairment did not predict future cognitive decline. These data are consistent with a causal effect of cognition on function. In particular, the data showed that a diminished cognitive ability is associated with a worse functional outcome at the subsequent visit, suggesting that cognitive decline will be followed by future functional decline.

Previous studies have investigated the relationship between clinical symptoms across the AD continuum and the underlying pathology of the disease and have suggested that signs of dementia might not occur until decades after the pathophysiological process begins [4–10]. Biomarker studies suggest that amyloid pathology may occur first followed by neurodegeneration and cognitive symptoms [11, 32]. Additionally, recent consensus statements postulate that targeting patients with earlier forms of the illness provide the best chance of slowing progression of the disease [10, 33–35]. Taken together, the findings from this post-hoc analysis support the concept that in patients with mild AD dementia, cognitive decline occurs early in the clinical manifestation on the AD continuum and, if effective, disease-modifying treatments may show effects on cognition prior to consequential effects on function.

The results from this post-hoc analysis corroborate the findings from a recent publication using similar methodologies [24]. Zahodne and colleagues applied ARCL panel analysis in two longitudinal studies, the WHICAP and the Predictors Study, which included non-demented older adults and mildly demented AD patients, respectively. They found that cognitive decline preceded and predicted subsequent functional decline both prior to and after dementia onset. Others have also reported that cognitive tests can predict future impairment on activities of daily living before onset of dementia [36–38] and some studies have even suggested functional changes can predict conversion from MCI to AD [39–41]. These studies have shown substantial variability in rates of conversion, consistent with the difficulty in identifying subtle functional changes. To our knowledge, there have not been other empirical data exploring the temporal relationship between cognition and function in patients with mild AD dementia.

Collectively, the conclusion that cognitive impairment precedes and predicts functional impairment is evidenced by replications across multiple independent datasets. This includes three clinical trial cohorts of mild AD dementia patients in this post-hoc analysis and two cohorts (one population-based and one clinical trial-based) in Zahodne et al. [24]. The validity is further strengthened by consistent results across different stages of the AD disease continuum as observed in previous and current studies (2013) (both older adults without dementia and mild AD patients). Additionally, although the coefficients in the ADNI and EXPEDITION/IDENTITY study programs are in opposite directions due to differences in scoring convention (with the higher score of FAQ and lower score of ADCS-ADL reflecting greater impairment), the magnitude and interpretation of the results are similar. These consistent findings are achieved despite the fact that different instruments and scales for cognition and function are used in the analyses, suggesting our findings are independent to scale selection.

As pointed out by other authors [21], the ARCL model is most useful in evaluating the temporal ordering of two outcomes and in supporting potential causal-effect directions in the relationships of the outcomes. ARCL is utilized in this research to investigate whether cognitive impairment precedes and predicts subsequent functional impairment, or vice versa. It is not the objective of this research to model precise quantitative measures of the trajectory of disease progression in AD dementia, which is a complex undertaking. Future research is needed to comprehensively characterize this quantitative relationship between cognition and function using more sensitive measures and additional representative models of disease progression.

While the ARCL panel analyses demonstrated that cognitive impairment predicts functional impairment in the natural course of the disease, an additional statistical approach has been used to investigate the influence of cognitive treatment effect on functional treatment effect. In a previous study, path analysis was used to assess the relationship between the treatment effect of solanezumab on the slowing of cognitive and functional decline using pooled data from patients with mild AD who participated in the EXPEDITION and EXPEDITION2 studies [25]. In that study, path analyses determined that the treatment effect on function was primarily driven by the direct treatment effect on cognition. Combined with the ARCL panel analyses, these findings support the idea that slowing cognitive impairment can be considered an intermediate step to slowing functional impairment in mild AD dementia.

There are limitations of these post-hoc analyses. Although the results were consistent across various clinical measures commonly used in AD clinical trials, the findings are based on existing cognitive and functional scales. More sensitive clinical diagnostic tools might reveal subtle changes in earlier disease stages, including mild AD dementia. For example, while ADAS-Cog and ADCS-iADL showed a good correlation based on current data, a cognitive scale that is more sensitive to executive function may establish an even stronger relationship and greater magnitude of association with activities of daily living [42, 43]. An optimized functional measure designed to assess very mild functional change and with culturally neutral elements, might be more applicable to a mildly affected patient population such as the ones studied here and may allow detection of greater magnitude of impact of cognitive impairment on functional impairment. Additionally, the power of the models may have been limited due to a smaller sample size of the ADNI dataset and the early termination of the IDENTITY program, leading to the reduced availability of data, especially toward the later time points of the study. Lastly, the analysis is limited to patients with mild AD dementia and there may be different cognitive-functional relationships in later, more severe disease states.

The early stages of symptomatic AD are primarily defined by cognitive impairment that may have clinical implications for patients even before functional impairment is measurable (e.g., patients with prodromal AD or MCI). Our analyses support the causal effect of cognitive impairment on subsequent functional impairment for patients with mild AD dementia. Disease-modifying treatments designed to disrupt underlying AD pathophysiology early in the disease process might be expected to slow the progression of cognitive symptoms, while effects on function may take longer to observe. If cognitive impairment precedes and predicts functional impairment in the natural course of AD, cognition may be used as an indicator of future functional outcomes and should be considered a critical target for prevention strategies to limit future functional decline. Taken together, understanding the temporal relationship between cognition and function has real world implications and may lead to more effective and efficient strategies for drug development in early AD. Further, it may enable appropriate expectations for outcomes with putative disease-modifying therapies studied in earlier stages of AD.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Studies and post-hoc analyses of studies were sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Clinical trialregistration identifiers: NCT00905372, NCT00904683,NCT00594568, NCT00762411.

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and DOD ADNI (Department of Defense award number W81XWH-12-2-0012). ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: Alzheimer’s Association; Alzheimer’s Drug Discovery Foundation; BioClinica, Inc.; Biogen Idec Inc.; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Eisai Inc.; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Eli Lilly and Company; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc.; GE Healthcare; Innogenetics, N.V.; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research & Development, LLC.; Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development LLC.; Medpace, Inc.; Merck and Company, Inc.; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc.; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Synarc Inc.; and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (http://www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the Northern California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Part of the data used in preparation of this article was obtained from the ADNI database (http://adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report.

The authors thank the Solanezumab and Semagacestat Study Groups, the patients for their voluntary participation, and the principal investigators. They also thank Michael Case and Ann Hake for their statistical and medical review, respectively, and Karen Holdridge and Laura Ramsey for their editorial assistance.

Authors’ disclosures available online (http://j-alz.com/manuscript-disclosures/14-2508r2).

References

1 | Albert MS, DeKosky ST, Dickson D, Dubois B, Feldman HH, Fox NC, Gamst A, Holtzman DM, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Snyder PJ, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Phelps CH(2001) The diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging – Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s diseaseAlzheimers Dement7: 270279 |

2 | Petersen RC, Smith GE, Waring SC, Ivnik RJ, Tangalos EG, Kokmen E(1999) Mild cognitive impairment: Clinicalcharacterization and outcomeArch Neurol56: 303308Erratum in: Arch Neurol 56,760. |

3 | Morris JC(2012) Revised criteria for mild cognitive impairment may compromise the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease dementiaArch Neurol69: 700708 |

4 | Sperling RA, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, Bennett DA, Craft S, Fagan AM, Iwatsubo T, Jack CRJr, Kaye J, Montine TJ, Park DC, Reiman EM, Rowe CC, Siemers E, Stern Y, Yaffe K, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Morrison-Bogorad M, Wagster MV, Phelps CH(2011) Toward defining the preclinical stages of Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the NationalInstitute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Association workgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s diseaseAlzheimers Dement7: 280292 |

5 | Morris JC, Roe CM, Grant EA, Head D, Storandt M, Goate AM, Fagan AM, Holtzman DM, Mintun MA(2009) Pittsburgh compound B imaging and prediction of progression from cognitive normality to symptomatic Alzheimer diseaseArch Neurol66: 14691475 |

6 | Rentz DM, Locascio JJ, Becker JA, Moran EK, Eng E, Buckner RL, Sperling RA, Johnson KA(2010) Cognition, reserve,and amyloid deposition in normal agingAnn Neurol67: 5364 |

7 | Knopman DS, Jack CJr, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Vemuri P, Lowe V, Kantarci K, Gunter JL, Senjem ML, Ivnik RJ, Roberts RO, Boeve BF, Petersen RC(2012) Short-term clinical outcomes for stages of NIA-AA preclinical AlzheimerDiseaseNeurology78: 15761582 |

8 | Ellis KA, Lim YY, Harrington K, Ames D, Bush AI, Darby D, Martins RN, Masters CL, Rowe CC, Savage G, Szoeke C, Villemagne VL, Maruff PResearch AIBL Group(2013) Decline in cognitive function over 18 months in healthyolder adults with high amyloid-βJ Alzheimers Dis34: 861871 |

9 | Villemagne VL, Burnham S, Bourgeat P, Brown B, Ellis KA, Salvado O, Szoeke C, Macaulay SL, Martins R, Maruff P, Ames D, Rowe CC, Masters CLAustralian Imaging Biomarkers, Lifestyle (AIBL) Research Group(2013) Amyloidβ deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: A prospectivecohort studyLancet Neurol12: 357367 |

10 | Bateman RJ, Xiong C, Benzinger TL, Fagan AM, Goate A, Fox NC, Marcus DS, Cairns NJ, Xie X, Blazey TM, Holtzman DM, Santacruz A, Buckles V, Oliver A, Moulder K, Aisen PS, Ghetti B, Klunk WE, McDade E, Martins RN, Masters CL, Mayeux R, Ringman JM, Rossor MN, Schofield PR, Sperling RA, Salloway S, Morris JCDominantly Inherited Alzheimer Network(2012) Clinical and biomarker changes in dominantly inherited Alzheimer’s diseaseN Engl J Med367: 795804 |

11 | Jack CRJr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Shaw LM, Aisen PS, Weiner MW, Petersen RC, Trojanowski JQ(2010) Hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkers of the Alzheimer’s pathological cascadeLancet Neurol9: 119128 |

12 | McKhann GM, Knopman DS, Chertkow H, Hyman BT, Jack CRJr, Kawas CH, Klunk WE, Koroshetz WJ, Manly JJ, Mayeux R, Mohs RC, Morris JC, Rossor MN, Scheltens P, Carrillo MC, Thies B, Weintraub S, Phelps CH(2011) The diagnosis ofdementia due to Alzheimer’s disease: Recommendations from the National Institute on Aging-Alzheimer’s Associationworkgroups on diagnostic guidelines for Alzheimer’s diseaseAlzheimers Dement7: 263269 |

13 | Dubois B, Feldman HH, Jacova C, Hampel H, Molinuevo JL, Blennow K, DeKosky ST, Gauthier S, Selkoe D, Bateman R, Cappa S, Crutch S, Engelborghs S, Frisoni GB, Fox NC, Galasko D, Habert MO, Jicha GA, Nordberg A, Pasquier F, Rabinovici G, Robert P, Rowe C, Salloway S, Sarazin M, Epelbaum S, de Souza LC, Vellas B, Visser PJ, Schneider L, Stern Y, Scheltens P, Cummings JL(2014) Advancing research diagnostic criteria for Alzheimer’s disease: TheIWG-2 criteriaLancet Neurol13: 614629 |

14 | Potkin SG, Anand R, Hartman R, Veach J, Grossberg G(2002) Impact of Alzheimer’s disease and rivastigmine treatment on activities of daily living over the course of mild to moderately severe diseaseProg Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry26: 713720 |

15 | Rosler M, Anand R, Cicin-Sain A, Gaultheir S, Agid Y, Dal-Bianco P, Stahelin HB, Hartman R, Gharabawi M(1999) Efficacy and safety of rivastigmine in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: International randomised controlled trialBMJ318: 633640 |

16 | Erkinjuntti T, Kurz A, Gauthier S, Bullock R, Lilienfeld S, Damaraju CV(2002) Efficacy of galantamine inprobable vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease combined with cerebrovascular disease: A randomized trialLancet359: 12831290 |

17 | Reisberg B, Doody R, Stöffler A, Schmitt F, Ferris S, Möbius HJMemantine Study Group(2003) Memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer’s diseaseN Engl J Med348: 13331341 |

18 | Rogers SL, Doody RS, Mohs RC, Friedhoff LT(1998) Donepezil improves cognition and global function in Alzheimer’s disease: A 15-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Donepezil Study GroupArch Intern Med158: 10211031 |

19 | Mohs RC(2001) A 1-year, placebo-controlled preservation of function survival study of donepezil in AD patientsNeurology57: 481488Erratum in 57, 1942 |

20 | Gao F, Thompson P, Xiong C, Miller JP(2006) Analyzing multivariate longitudinal data Using SASProceedingsof SAS Users Group International 2006 meeting (SUGI31)187931 |

21 | Selig JP, Little TD (2012) Handbook of Developmental Research Methods Autoregressive and cross-lagged panelanalysis for longitudinal data. Chapter 16 Laursen B, Little TD, Card NA New York, NY Guilford Press 265 278 |

22 | Song TM, An J-Y, Hayman LL, Kim GS, Lee JY, Jang HL(2012) A three-year autoregressive crosslagged panel analysis on nicotine dependence and average smokingHealthc Inform Res18: 115124 |

23 | Burns JW, Glenn B, Bruehl S, Harden RN, Lofland K(2003) Cognitive factors influence outcome following multidisciplinary chronic pain treatment: A replication and extension of a cross-lagged panel analysisBehav Res Ther41: 11631182 |

24 | Zahodne LB, Manly JJ, MacKay-Brandt A, Stern Y(2013) Cognitive declines precede and predict functional declines in aging and Alzheimer’s diseasePLoS One8: e73645 |

25 | Liu-Seifert H, Siemers E, Sundell K, Price K, Han B, Selzler K, Aisen P, Cummings J, Raskin J, Mohs R(2015) Cognitive and functional decline and their relationship in patients with mild Alzheimer’s dementiaJAlzheimers Dis43: 949955 |

26 | Doody RS, Thomas RG, Farlow M, Iwatsubo T, Vellas B, Joffe S, Kieburtz K, Raman R, Sun X, Aisen PS, Siemers E, Liu-Seifert H, Mohs RAlzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Steering Committee, Solanezumab Study Group(2014) Phase 3 trials of solanezumab for mild-to-moderate Alzheimer’s diseaseN Engl J Med370: 311321 |

27 | Mohs RC, Knopman D, Petersen RC, Ferris SH, Ernesto C, Grundman M, Sano M, Bieliauskas L, Geldmacher D, Clark C, Thal LJ(1997) Development of cognitive instruments for use in clinical trials of antidementia drugs: Additionsto the Alzheimer’s disease assessment scale that broaden its scopeAlzheimer Dis Assoc Disord11: S13S21 |

28 | Doody RS, Raman R, Farlow M, Iwatsubo T, Vellas B, Joffe S, Kieburtz K, He F, Sun X, Thomas RG, Aisen PS, Siemers E, Sethuraman G, Mohs R(2013) A Phase 3 Trial of Semagacestat for Treatment of Alzheimer’s DiseaseN EnglJ Med369: 341350 |

29 | [ADNI] Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative, http://adni.loni.usc.edu/, Accessed 20 August 2014 |

30 | Rosen WG, Mohs RC, Davis KL(1984) A new rating scale for Alzheimer’s diseaseAm J Psychiatry141: 13561364 |

31 | Pfeffer RI, Kurosaki TT, Harrah CHJr, Chance JM, Filos S(1982) Measurement of functional activities in older adults in the communityJ Gerontol37: 323329 |

32 | Jack CRJr, Knopman DS, Jagust WJ, Petersen RC, Weiner MW, Aisen PS, Shaw LM, Vemuri P, Wiste HJ, Weigand SD, Lesnick TG, Pankratz VS, Donohue MS, Trojanowski JQ(2013) Tracking pathophysiological processes in Alzheimer’sdisease: An updated hypothetical model of dynamic biomarkersLancet Neurol12: 207216 |

33 | Cummings JL, Doody R, Clark C(2007) Disease-modifying therapies for Alzheimer disease: Challenges to early interventionNeurology69: 16221634 |

34 | Sperling RA, Jack CRJr, Aisen PS(2011) Testing the right target and right drug at the right stageSci Transl Med3: 111cm33 |

35 | Vellas B, Andrieu S, Sampaio C, Wilcock GEuropean Task Force group(2007) Disease-modifying trials in Alzheimer’s disease: A European task force consensusLancet Neurol6: 5662 |

36 | Njegovan V, Hing MM, Mitchell SL, Molnar FJ(2001) The hierarchy of functional loss associated with cognitive decline in older personsJ Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci56: M638M643 |

37 | Ishizaki T, Yoshida H, Suzuki T, Watanabe S, Niino N, Ihara K, Kim H, Fujiwara Y, Shinkai S, Imanaka Y(2006) Effects of cognitive function on functional decline among community-dwelling non-disabled older JapaneseArch Gerontol Geriatr42: 4758 |

38 | Fujiwara Y, Yoshida H, Amano H, Fukaya T, Liang J, Uchida H, Shinkai S(2008) Predictors of improvement ordecline in instrumental activities of daily living among community-dwelling older JapaneseGerontology54: 373380 |

39 | Amieva H, Le Goff M, Millet X, Orgogozo JM, Pérès K, Barberger-Gateau P, Jacqmin-Gadda H, Dartiques JF(2008) Prodromal Alzheimer’s disease: Successive emergency of clinical symptomsAnn Neurol64: 492498 |

40 | Reppermund S, Brodaty H, Crawford JD, Kochan NA, Draper B, Slavin MJ, Trollor JN, Sachdev PS(2013) Impairment ininstrumental activities of daily living with high cognitive demand is an early marker of mild cognitiveimpairment: The Sydney Memory and Aging StudyPsychol Med11: 19 |

41 | Grundman M, Petersen RC, Bennett DA, Feldman HH, Salloway S, Visser PJ, Thal LJ, Schenk D, Khachaturian Z, Thies WAlzheimer’s Association Research, Roundtable(2006) Alzheimer’s Association Research Roundtable Meeting onMild Cognitive Impairment: What have we learned?Alzheimers Dement2: 220233 |

42 | Martyr A, Clare L(2012) Executive function and activities of daily living in Alzheimer’s disease: A correlational meta-analysisDement Geriatr Cogn Disord33: 189203 |

43 | Swanberg MM, Tractenberg RE, Mohs R, Thal LJ, Cummings JL(2004) Executive dysfunction in Alzheimer diseaseArch Neurol61: 556560 |

Figures and Tables

Fig.1

Path diagram of the autoregressive cross-lagged panel analysis model to assess the interrelationship between cognitive and functional longitudinal data. Autoregressive and cross-lagged coefficients (β, γ) were estimated from time (t-1) to time (t) for cognition and function, and the correlations between the two outcome variables (ρ) was also estimated (modified from Zahodne et al. [24]).

![Path diagram of the autoregressive cross-lagged panel analysis model to assess the interrelationship between cognitive and functional longitudinal data. Autoregressive and cross-lagged coefficients (β, γ) were estimated from time (t-1) to time (t) for cognition and function, and the correlations between the two outcome variables (ρ) was also estimated (modified from Zahodne et al. [24]).](https://content.iospress.com:443/media/jad/2015/47-1/jad-47-1-jad142508/jad-47-1-jad142508-g001.jpg)

Fig.2

Correlations between cognitive and functional measures in EXPEDITION, IDENTITY, and ADNI study programs. EXPEDITION and IDENTITY include mild AD dementia patients treated with placebo. ADNI includes mild AD dementia patients with no investigational treatment. All correlations include absolute values for comparisons across the different scales. EXPEDITION and IDENTITY compared ADAS-Cog14 versus ADCS-iADL and ADNI compared ADAS-Cog11 versus FAQ.

Table 1

Patient Demographics in mild AD Dementia

| Category | EXPEDITION Placebo (n = 663) | IDENTITY Placebo (n = 629) | ADNI (n = 336) |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 73.3 (7.9) | 73.6 (7.9) | 75.1 (7.8) |

| Female % | 54.6 | 53.7 | 44.4 |

| Race, white % | 84.2 | 74.7 | 92.7 |

| APOE4 carriers % | 59.8 | 57.1 | 67.2 |

| Education, mean (SD), years | 12.6 (3.9) | 12.5 (3.8) | 15.2 (3.0) |

| MMSE (baseline), mean (SD) | 22.5 (2.8) | 22.7 (2.7) | 23.2 (2.1) |

EXPEDITION and IDENTITY include mild AD dementia patients treated with placebo. ADNI includes mild AD dementia patients with no investigational treatment. ADNI, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; MMSE, Mini Mental State Examination; SD, standard deviation.

Table 2

Cognitive and functional scores at each time point in mild AD dementia

| Months | Cognitiona Mean (SD) | Functionb Mean (SD) | |

| EXPEDITION Placebo | Baseline | 29.6 (8.8) | 43.9 (9.5) |

| 3 | 29.8 (9.6) | 42.0 (10.2) | |

| 6 | 30.9 (10.8) | 41.3 (10.7) | |

| 9 | 30.9 (11.5) | 40.5 (10.8) | |

| 12 | 33.4 (12.1) | 39.6 (11.4) | |

| 15 | 34.0 (13.1) | 38.4 (11.9) | |

| 18 | 35.8 (14.4) | 37.1 (12.8) | |

| IDENTITY Placebo | Baseline | 30.2 (8.6) | 41.6 (10.9) |

| 3 | 30.0 (9.2) | 41.1 (10.6) | |

| 6 | 30.9 (10.3) | 40.1 (11.4) | |

| 9 | 30.8 (11.0) | 39.7 (11.2) | |

| 12 | 33.2 (11.9) | 39.0 (11.9) | |

| 15 | 34.1 (12.8) | 37.8 (12.3) | |

| 18 | 34.0 (14.1) | 37.7 (12.3) | |

| ADNI | Baseline | 19.7 (6.8) | 13.2 (7.0) |

| 6 | 21.5 (7.9) | 15.5 (7.4) | |

| 12 | 22.8 (8.8) | 17.3 (7.2) | |

| 24 | 27.9 (11.9) | 20.3 (7.1) |

EXPEDITION and IDENTITY include mild AD dementia patients treated with placebo. ADNI includes mild AD dementia patients with no investigational treatment. aCognitive measures included: ADAS-Cog14 for EXPEDITION and IDENTITY study programs; ADAS-Cog11 for ADNI. bFunctional measures included: ADCS-iADL for EXPEDITION and IDENTITY study programs; FAQ for ADNI. ADAS-Cog, AD Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscales; ADCS-iADL, AD Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living instrumental subscale; ADNI, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; FAQ, Functional Activities Questionnaire; SD, standard deviation.

Table 3

Model fit statistics for ARCL panel analyses in mild AD dementia

| RMSEA | RMSEA 90% CI | SRMR | CFI | |

| EXPEDITION Placebo | 0.04 | (0.03, 0.05) | 0.06 | 0.99 |

| IDENTITY Placebo | 0.07 | (0.06, 0.09) | 0.05 | 0.98 |

| ADNI | 0.08 | (0.03, 0.12) | 0.02 | 0.99 |

EXPEDITION and IDENTITY include mild AD dementia patients treated with placebo. ADNI includes mild AD dementia patients with no investigational treatment. All regression coefficients are standardized. ADNI, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; ARCL, autoregressive cross-lagged; CFI, comparative fit index; CI, confidence interval; RMSEA, root mean square error of approximation; SRMR, Standardized root mean square residual.

Table 4

ARCL panel analysis results for the 3 patient cohorts with mild AD dementia

| Regression effect | Cognition on function estimate (SE) | Function on cognition estimate (SE) | |

| EXPEDITION Placebo | Baseline predicting 3 Month | −0.06 (0.03) * | −0.03 (0.03) |

| 3 Month predicting 6 Month | −0.09 (0.03) ** | 0.03 (0.03) | |

| 6 Month predicting 9 Month | −0.04 (0.03) | 0.06 (0.03) * | |

| 9 Month predicting 12 Month | −0.06 (0.03) * | −0.04 (0.03) | |

| 12 Month predicting 15 Month | −0.06 (0.03) * | 0.05 (0.03) | |

| 15 Month predicting 18 Month | −0.11 (0.02) *** | −0.01 (0.02) | |

| IDENTITY Placebo | Baseline predicting 3 Month | −0.07 (0.04) | 0.09 (0.06) |

| 3 Month predicting 6 Month | −0.09 (0.04) * | −0.03 (0.05) | |

| 6 Month predicting 9 Month | −0.09 (0.04) * | 0.01 (0.4) | |

| 9 Month predicting 12 Month | −0.13 (0.04) ** | 0.03 (0.04) | |

| 12 Month predicting 15 Month | −0.07 (0.04) | −0.02 (0.04) | |

| 15 Month predicting 18 Month | −0.03 (0.04) | 0.04 (0.04) | |

| ADNI | Baseline predicting 6 Month | −0.01 (0.07) | 0.05 (0.08) |

| 6 Month predicting 12 Month | 0.09 (0.05) | 0.08 (0.07) | |

| 12 Month predicting 24 Month | 0.19 (0.06) *** | −0.06 (0.06) |

*p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001. EXPEDITION and IDENTITY include mild AD dementia patients treated with placebo. ADNI includes mild AD dementia patients with no investigational treatment. All regression coefficients are standardized. Cognitive measures included: ADAS-Cog14 for EXPEDITION and IDENTITY study programs; ADAS-Cog11 for ADNI. Functional measures included: ADCS-iADL for EXPEDITION and IDENTITY study programs; FAQ for ADNI. Note: significant coefficients are positive for only the ADNI dataset due to the difference in directionality of the functional measures (higher ADCS-iADL and lower FAQ scores reflect more impairment). ADAS-Cog, AD Assessment Scale-Cognitive subscales; ADCS-iADL, AD Cooperative Study-Activities of Daily Living instrumental subscale; ADNI, Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative; ARCL, autoregressive cross-lagged; FAQ, Functional Activities Questionnaire; SE, standard error.