- MRC Centre for Inflammation Research, Queen’s Medical Research Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom

Apoptosis and subsequent phagocytic clearance of apoptotic cells is important for embryonic development, maintenance of tissues that require regular cellular renewal and innate immunity. The timely removal of apoptotic cells prevents progression to secondary necrosis and release of cellular contents, preventing cellular stress and inflammation. In addition, altered phagocyte behavior following apoptotic cell contact and phagocytosis engages an anti-inflammatory phenotype, which impacts upon development and progression of inflammatory and immune responses. Defective apoptotic cell clearance underlies the development of various inflammatory and autoimmune diseases. There is considerable functional redundancy in the receptors that mediate apoptotic cell clearance, highlighting the importance of this process in diverse physiological processes. A single phagocyte may utilize multiple receptor pathways for the efficient capture of apoptotic cells by phagocytes (tethering) and the subsequent initiation of signaling events necessary for internalization. In this review, we will consider the surface alterations and molecular opsonization events associated with apoptosis that may represent a tunable signal that confers distinct intracellular signaling events and hence specific phagocyte responses in a context-dependent manner. Efficient molecular communication between phagocytes and apoptotic targets may require cooperative receptor utilization and the establishment of efferocytic synapse, which acts to stabilize adhesive interactions and facilitate the organization of signaling platforms that are necessary for controlling phagocyte responses.

Introduction

Elimination of injured or metabolically stressed cells in multicellular organisms is controlled via engagement of apoptotic programs together with efficient tissue clearance mechanisms (1–3). Phagocyte/apoptotic cell interactions also initiate anti-inflammatory reprogramming that regulates inflammation and immunity (4). Deficient clearance of apoptotic cells contributes to the development and/or exacerbation of many autoimmune and inflammatory diseases [reviewed in Ref. (5)].

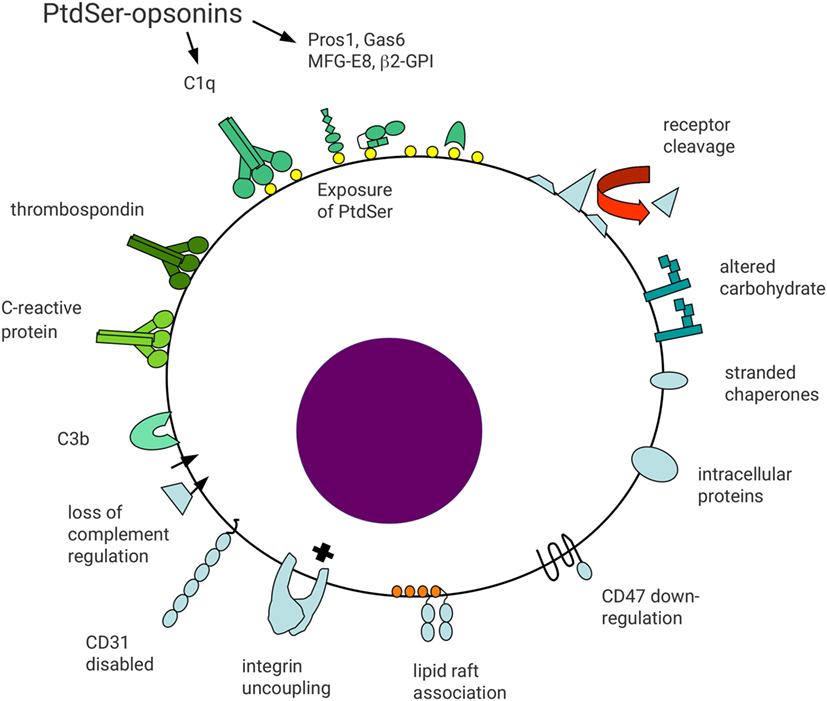

The diversity of molecular pathways mediating recognition and phagocytosis of apoptotic cells (efferocytosis) reflects the fundamental importance of this process (4). There are several mechanisms by which viable cells avoid phagocytosis (6). However, altered plasma membrane lipid composition (7, 8) and/or oxidation status (9), together with changes in cell surface molecule repertoire and patterns of glycosylation (10) termed “apoptotic cell associated molecular patterns” (11) (Figure 1), allow phagocytes to distinguish viable and apoptotic cells. Here, we consider the formation of an “efferocytic synapse” and assembly of molecular platforms that facilitate phagocytosis and subsequent signaling events.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of surface molecular changes associated with apoptosis. Reduced cell surface molecule expression may occur through metalloprotease-mediated proteolytic shedding. Reduced receptor expression may act to limit apoptotic cell function and generate a distinct cell surface profile from viable cells. For example, reduced expression of CD47 or disabled CD31 may lead to loss of signals preventing phagocytosis. In addition, loss of integrin regulation may result in functional uncoupling in apoptotic cells, leading to cell detachment. Altered association of cell surface molecules with lipid rafts may alter functional activity, including gain-of-function of some receptors, e.g., FcγRIIa on myeloid cells. Altered carbohydrate processing may result in reduced sialic acid exposure and appearance of accessible mannose residues. Downregulation of complement regulatory molecules (e.g., CD55 and CD46) may lead to opsonization with complement components including C3b. Exposure of anionic phospholipids, including phosphatidylserine (PtdSer), allows binding of a broad range of opsonins to apoptotic cells. Protein S and Gas6 bind to PtdSer in a Ca2+-dependent manner, whereas milk fat globule EGF-factor 8 (MFG-E8) binds independent of Ca2+. Other less well defined apoptotic cell surface changes may allow binding of other opsonins including thrombospondin, C-reactive protein, and surfactant protein A. Finally, proteins with intracellular localizations may appear on the surface of apoptotic cells, including heat-shock proteins and calreticulin. Apoptotic cell surface molecules are shaded blue whereas apoptotic cell opsonins are shaded green.

Phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) as a Ligand for Apoptotic Cell Recognition

A near universal membrane alteration associated with apoptosis is the caspase-dependent exposure of PtdSer on the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane (12–14) via the XK-related protein 8 (15). Exposure of PtdSer affects the biophysical characteristics and organization of the plasma membrane through recruitment of proteins to PtdSer-enriched regions via electrostatic interactions (16). Phagocytes express transmembrane receptors that bind PtdSer directly, e.g., brain-specific angiogenesis inhibitor-1 (BAI-1) (17) and stabilin-2 (18). In addition, soluble molecules such as transthyretin-like protein TTR-52 (19), milk fat globule EGF-factor 8 (MFG-E8) (20, 21), protein S (Pros1), Gas6 (22) and C1q (23) also bind to (and opsonize) PtdSer, providing a scaffold for phagocyte recognition via a diverse array of counter-receptors.

Phagocytes fail to engulf viable cells that expose low levels of PtdSer during activation (24–26) or when PtdSer exposure is induced by overexpression of a phospholipid scramblase, transmembrane protein 16F (TMEM16F) (27), suggesting that additional signals are necessary to initiate efferocytosis. A critical threshold of PtdSer exposure on the cell surface may be required to trigger efferocytosis (28). For example, recognition of PtdSer via T-cell immunoglobulin and mucin-domain-containing molecule (TIM)-4 was dependent on ligand density, allowing phagocytes to distinguish between high and low level PtdSer exposure (28). Further modifications of PtdSer during apoptosis, e.g., oxidation or formation of lyso-PtdSer (29) may also be important.

Cell Surface Receptor Alterations Associated with Apoptosis

Apoptosis-dependent loss of cell surface receptors or appearance of “new” molecules may confer recognition by phagocytes. For example, signaling via Signal regulatory protein-α (SIRPα) inhibits myosin-II-mediated phagocytosis (30). Downregulation of ligands for SIRPα, e.g., CD47 (31), from the surface of apoptotic cells would be predicted to promote efferocytosis (32, 33). SIRPα-mediated signaling has also been reported to be triggered by binding of surfactant protein (SP)-A and SP-D to phagocytes. However, SP-A may have a dual role in regulation of phagocytosis as binding to apoptotic cells/debris results in promotion of phagocytosis via a calreticulin/CD91-mediated pathway (34). Early experiments identified a unique charge-sensitive mechanism for apoptotic cell recognition (35). The cell glycocalyx provides a negative surface charge “repulsive” force that counters cell–cell interactions (36). Loss of N-terminal sialic acid and exposure of mannose and fucose moieties during apoptosis reduces electrostatic forces that counter phagocyte recognition (37–39). In addition, the surface charge of apoptotic cells is further altered by reduced expression of heavily sialylated proteins (e.g., CD43, CD45, and CD162) (37). Consistent with this suggestion, removal of sialic acid from the cell surface by neuraminidase treatment enhances phagocytosis (37, 39).

Apoptosis is associated with loss of expression of complement regulatory proteins such as CD46/CD55 (40, 41). As a result, deposition of complement may occur, providing a cue for recognition by phagocytes. Additional signals for phagocytosis may occur as a result of exposure of intracellular proteins such as calreticulin (42) and annexin I (43). Following binding to PtdSer on apoptotic cells, oxidation of Pros1 induces oligomerization, which promotes Mer-dependent phagocytosis (44). Similarly, altered glycosylation of membrane proteins or oxidization of low-density lipoprotein-like moieties on apoptotic cells (8) may also contribute to the specific recognition by phagocytes. In addition to increased expression of ligands for phagocytic receptors on apoptotic cells, patching and/or clustering of surface molecules may also have important consequences for triggering phagocyte responses. Clustering might occur through specific association with membrane microdomains. For example, FcγRIIa redistributes to membrane microdomains during neutrophil apoptosis (45). In addition, specific proteolysis of adhesion molecules (e.g., CD62L) (46, 47) and uncoupled β2 integrin-mediated adhesion (47) during apoptosis is likely to provide additional molecular cues for phagocytosis.

Phagocyte Molecules that Mediate Apoptotic Cell Recognition

Phagocytes are capable of direct recognition of PtdSer exposed on the apoptotic cell surface. BAI-1 binds PtdSer via thrombospondin (TSP) type 1 repeats present in the extracellular domain (48). Binding induces the formation of a trimeric complex of BAI-1 with the Rac-GEF ELMO and DOCK180 that promotes subsequent engulfment of apoptotic cells (17, 49). This pathway is homologous to the genetically defined pathway for removal of apoptotic cells in Caenorhabditis elegans (Ced2-CrkII, Ced5-DOCK180, Ced10-Rac, and Ced12-ELMO) (50).

Phosphatidylserine is also recognized by the CD300 family of molecules with an extracellular IgV-like domain and intracellular adaptor molecule binding sites (51). CD300b localizes to phagocytic cups and binds DAP12, activating Syk and PI3K/Akt to promote phagocytosis (52). Stabilin-2 binds PtdSer and also lacks direct signaling activity (18). However, the cytoplasmic domain of stabilin-2 can interact with GULP to facilitate phagocytosis (53). GULP also binds to NPxY motifs present in the cytoplasmic domains of CD91/LRP (low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein) and the C. elegans scavenger receptor Ced-1 (54). In contrast, TIM-4 confers Ca2+-dependent PtdSer-dependent apoptotic cell recognition, but lacks intracellular signaling potential (55). Thus, TIM-4 functions cooperatively with other receptors that trigger apoptotic cell internalization.

Indirect recognition of apoptotic cells by phagocytes is also achieved by phagocyte receptors that bind to soluble apoptotic cell opsonins. In C. elegans, TTR-52 bridges apoptotic cell-exposed PtdSer to phagocyte Ced-1 (19), which together with Ced-6 initiates rapid and efficient engulfment of apoptotic cell corpses by neighboring cells. This module of proteins (Ced1-MEGF-10; Ced6-GULP; and Ced7-ABCA1) has been defined genetically in C. elegans (50). Pros1 and Gas6 contain a Gla-domain that binds PtdSer in a Ca2+-dependent manner (22), bridging to the Tyro3/Axl/Mer receptor tyrosine kinases that signal particle internalization via intrinsic kinase activity (56). By contrast, MFG-E8 binds PtdSer in a Ca2+-independent manner and bridges to phagocyte integrins αvβ3/5 via arginine–glycine–aspartic acid (RGD) peptide motifs in the C1 and C2 domains (21). TSP-1 also bridges apoptotic cells via the phagocyte integrin αvβ3 and CD36 (57, 58).

Cooperative Receptor Utilization in Phagocytosis of Apoptotic Cells

Phagocytes in different tissue settings or microenvironments express distinct repertoires of efferocytic receptors. Whether a single phagocytic cell utilizes multiple receptor pathways to recognize and internalize a single apoptotic target is not clear. However, the distinct molecular requirements for the capture and subsequent internalization may require that multiple receptors are involved (42). In addition, the complex topology of apoptotic cell surface molecules and co-opsonization of PtdSer with different proteins may determine the spectrum of signal transduction pathways engaged, controlling internalization and subsequent phagocyte responses in a context-dependent manner.

Tethering of IgG-opsonized particles to FcγR occurs at 4°C (59) whereas internalization requires cytoskeletal reorganization and metabolic activity (60). Similarly, apoptotic cells can also be tethered by phagocytes via Mer at low temperature (61). However, the avidity of low affinity receptors is influenced by receptor density and rapid lateral movement of receptors to facilitate target capture (62, 63). Receptor mobility is controlled by cytoskeletal constraint, association with membrane lipid microdomains and/or other membrane proteins (64). For example, cytoskeletal-associated CD44 restricts membrane lipid and receptor motility via interactions with hyaluronan, forming a glycosaminoglycan barrier that reduces binding of phagocytic targets (36). Interestingly, CD44 cross-linking with antibody augments macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic cells, possibly as a result of changes in cytoskeletal regulation (65, 66). Phagocytic targets are bound at dynamic extensions of phagocytic cells, including filopodia and membrane ruffles (67), and receptor aggregation is required for orchestration of cytoskeletal alterations necessary for internalization [see Ref. (68) for a comprehensive review of cytoskeletal regulation in phagocytic synapses].

In contrast with IgG or complement attached to components of the microbial cell wall, molecules on the surface of apoptotic cells may exhibit unrestricted lateral mobility as a consequence of proteolytic cleavage of actin during apoptosis (69). Thus, there may be key mechanistic differences between efferocytosis and FcγR-dependent phagocytosis. Engagement of freely mobile molecules by phagocyte receptors may lead to assembly of receptor microclusters and significantly impact upon phagocytosis (33). Alternatively, opsonization of apoptotic cells may result in formation of immobile molecular complexes [like annexin V (70, 71)] that promote redistribution of phagocytic receptors necessary for signaling of internalization.

Molecular Segregation and the Formation of a Phagocytic “Synapse”

The cellular contact between phagocyte and apoptotic cells has parallels with those of antigen-specific T and B cells with antigen presenting cells that leads to establishment of an immunological synapse (72). This specialized intercellular contact zone stabilizes adhesion and facilitates efficient molecular communication following antigen-specific interactions. A number of different biophysical factors (including receptor density, ligand-binding affinity, molecular dimensions, and interactions with cytoskeletal elements) all contribute to the dynamic redistribution of adhesion and signaling receptors into distinct regions in the plasma membrane (73, 74).

Following phagocyte contact with IgG-coated surfaces or on supported lipid bilayers, formation of FcγRII nanoclusters suggests activation-driven organization of receptor redistribution (75). FcγR clusters are localized in front of ruffles on extending pseudopods, with rapid recruitment of Syk to advancing pseudopods and subsequent retrograde movement toward the cell center (76). PI3K co-localized with actin around FcγR clusters, suggestive of signal propagation from FcγR and consistent with PI3K-dependent control of actin cytoskeletal rearrangements (76).

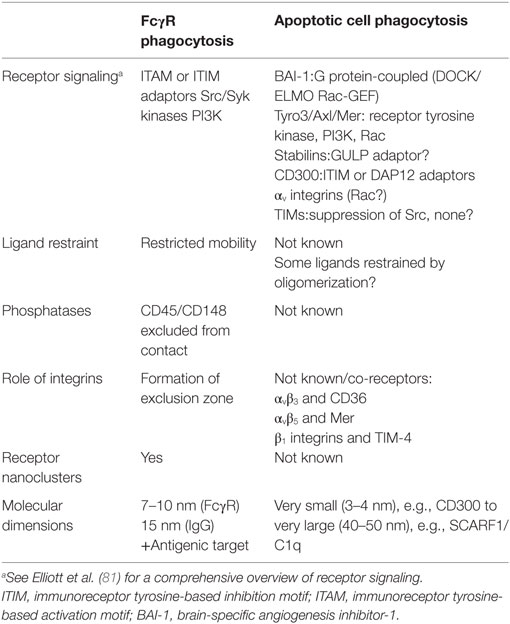

Although phagocyte contact with apoptotic cells has not been examined with the high-resolution imaging techniques used in T cell–APC interactions, molecular segregation may also be a key feature of the formation of efferocytic synapses (see Table 1). For example, exclusion of phosphatases (e.g., CD45) from the immune synapse is a critical early event in the initiation of T cell receptor-mediated phosphorylation of Zap70 and Lck (77). Changes in the distribution of CD45 may also represent a general feature of membrane alterations that control signaling events associated with phagocytosis. The C-type lectin containing receptor for β-glucan, Dectin-1, mediates the recognition and phagocytosis of yeast particles. During Dectin-1-mediated phagocytosis, exclusion of CD45 and the receptor type protein tyrosine phosphatase CD148 from the nascent phagocytic cup (78) is important for signaling associated with particle internalization (79). Redistribution of phosphatases in the phagocyte membrane would likely be necessary for internalization of apoptotic cells.

Table 1. Comparison of phagocytic synapse formation in FcγR-mediated and apoptotic cell phagocytosis.

Analysis of the molecular basis of redistribution of CD45 following ligation of FcγR suggests non-linear pattern with formation of an exclusion barrier which restricts access of CD45 to the contact site (79). CD45 is a relatively rigid molecule that extends axially from the plasma membrane approximately 20 nm (81). Similar to the molecular redistribution that occurs during immune synapse formation, exclusion from phagocytic synapses was dependent on the axial molecular dimensions of CD45. In experiments using chimeric constructs in which the extracellular portion of CD45 was replaced by either CD43 (similar length) or CD2 (shorter length), the CD43/CD45 molecule was excluded from the phagocytic synapse, whereas CD2/CD45 was not (79). A requirement for integrins and cytoskeletal regulation was shown to be necessary to establish a CD45 exclusion zone that extended beyond the IgG layer (79). These results suggest that integrin-mediated contact between phagocyte and phagocytic targets facilitates engagement of phagocytic receptors at low ligand densities or when binding to larger particles.

For apoptotic cell recognition, it is intriguing that integrins have been proposed to act cooperatively with other receptors to mediate phagocytosis. For example, αv integrins and CD36 are both required for the recognition of TSP-1 bound to apoptotic cells (58). Similarly, phagocytosis of apoptotic cells via TIM-4 requires β1 integrins and activation of integrin-dependent signaling involving Src family kinases and FAK (82). Furthermore, interactions between the β5 integrin and stabilin-2 were found to promote phagocytosis of apoptotic cells (83). Similarly, co-expression of αvβ5 with Mer increased activation of Rac-1, cytoskeletal regulation and the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells (84). Integrins can directly mediate the recognition of apoptotic cell opsonins, for example, RGD-dependent binding of MFG-E8 (21) or fibronectin (85). However, phagocytosis of apoptotic targets is increased following macrophage adhesion to extracellular matrix via β1 integrins (86) and is compromised following exposure to oxidized extracellular matrix molecules (87). We would speculate that, as for FcγR-mediated phagocytosis, integrin signaling can regulate cytoskeletal organization and facilitate tethering/phagocytosis of apoptotic cells with low-level opsonization (36).

For human macrophage-like cells, CD47 expression acts to limit phagocytosis of IgG-opsonized erythrocytes (30). CD47 binds to phagocyte SIRPα, resulting in recruitment to the phagocytic synapse, decreasing the accumulation of non-muscle myosin IIa and levels of tyrosine phosphorylation (30). Localization of SIRPα to the site of cell contact would recruit inhibitory tyrosine phosphatases such as SHP-1 via ITIM motifs present in the SIRPα cytoplasmic domain (88). In the absence of CD47 or when CD47 was blocked with antibody, phagocytosis was increased. Specific membrane receptors are organized into protein islands in unactivated T cells that subsequently coalesce as a consequence of T cell receptor-mediated signaling (89). The membrane distribution of SIRPα and FcγR during phagocytosis has been further analyzed using super-resolution microscopy. When macrophages were plated onto poly-l-lysine-coated slides, molecular clusters containing both FcγRI and SIRPα were observed (75). These molecules were found to segregate into discrete nanoclusters when macrophages were plated onto IgG. Interestingly, IgG promoted the formation of concentric rings of FcγRI and FcγRII, with FcγRI redistributing more rapidly (<10 min). Similar results were obtained when macrophages interacted with IgG in a supported lipid bilayer. When recombinant CD47 was included into the supported lipid bilayer, segregation of FcγR and SIRPα and the formation of concentric rings of FcγR were blocked. Thus co-localization of SIRPα and FcγR inhibits cellular activation following FcγR ligation, whereas segregation of these two molecules leads to activation (75). We would speculate that efferocytic receptors would also be present in dynamically regulated nanoclusters in the phagocyte membrane.

Molecular Dimensions and Apoptotic Cell Recognition

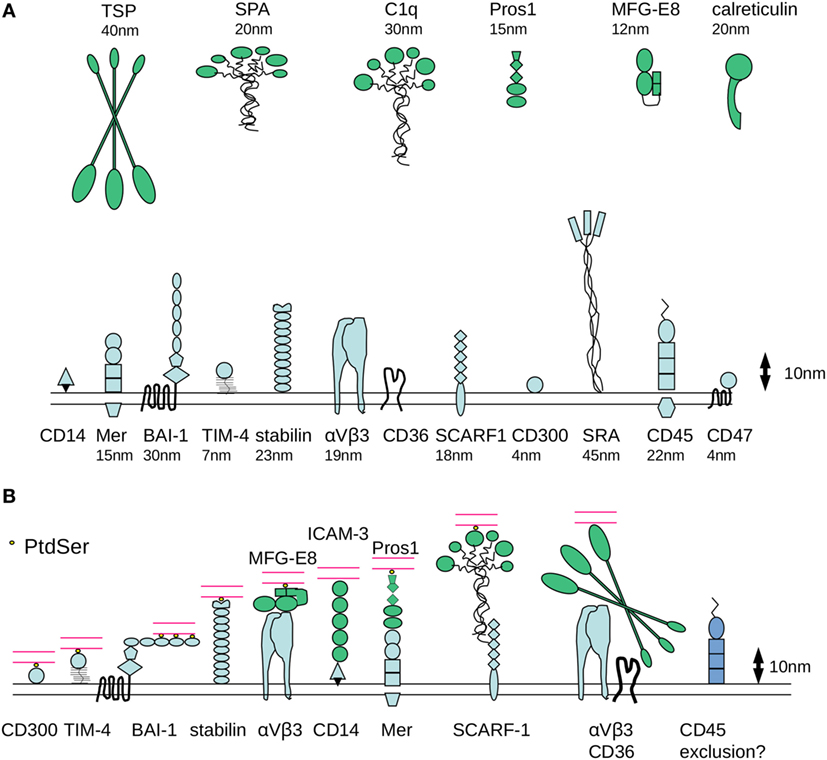

Size-dependent redistribution of molecules within the phagocyte membrane may represent an important organizing principle for the assembly of molecular platforms that are essential for signaling the cytoskeletal alterations required for the internalization of apoptotic cells. Estimation of the molecular dimensions of receptors involved in efferocytosis using published structural data (51, 90–106) reveals considerable differences in axial dimensions (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Molecular dimensions of proteins involved in phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. (A) Some of the major families of receptors that have been identified as having a role in the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells are depicted, drawn approximately to scale based on available published crystallographic/NMR or cryo-electron microscopy data for various protein domains. One assumption made is that the molecules have a relatively rigid structure, although it is possible that flexibility would considerably alter axial length. There are considerable differences in the dimensions of apoptotic cell opsonins and in the receptors that mediate binding of phosphatidylserine (PtdSer) binding (either directly or indirectly). (B) Example receptor–counter-receptor pairings are shown to illustrate the likely differences in intermembrane “working” distance during phagocytosis, particularly for the molecules involved in the recognition of PtdSer (shown in yellow). Phagocyte receptors are shown in blue, opsonins are shown in green, and the apoptotic cell membrane is shown in red.

First, it is notable that CD300 (single Ig-like domain) and TIM-4 (single Ig-like domain with a potentially rigid mucin-like stalk), which mediate direct recognition of PtdSer, are predicted to span a relatively short intermembrane distance between phagocyte and target (4 and 7 nm, respectively, Figure 2B). By contrast, stabilin-2, which also binds to PtdSer, is a much longer molecule extending some 23 nm. Assuming a degree of structural flexibility, BAI-1 may be capable of functioning in a broad range of intermembrane distances. The extracellular region of BAI-1 contains 5 TSP type 1 repeats (around 5 nm in size) with LPS and PtdSer binding motifs, which together with the GAIN/HBD regions could extend to ~33 nm from the plasma membrane. Following initial tethering of PtdSer by the N-terminal TSP repeat, BAI-1 could align parallel to the apoptotic cell surface as additional TSP repeats become ligated (Figure 2B). Nevertheless, it seems likely that a degree of molecular segregation would be required for these different receptors to be involved in apoptotic cell uptake on the same phagocyte.

Second, receptors such as SR-A or LRP are predicted to be highly extended molecules (~40–50 nm). In addition, some of the well characterized opsonins for apoptotic cells are extremely large. For example, C1q is approximately 30 nm and TSP-1 is 40–50 nm. Together with the relatively large counter receptors for these opsonins [e.g., SCARF1 for C1q (107) and αvβ3 for TSP], the predicted intermembrane contact distance would likely be incompatible with those of BAI-1, αvβ5/MFG-E8, or Mer/Protein S. One possibility is that these extended structures are efficient in the initial capture of apoptotic targets, facilitating subsequent engagement of receptor/counter-receptor pairs that span a smaller intermembrane distance and are influenced by electrostatic repulsion between cells.

Third, receptors of the Tyro3/Axl/Mer family, BAI-1, and the integrin αvβ5 are able to initiate intracellular signaling that controls particle internalization. If there are parallels with immunological synapse formation, these receptors might be expected to become localized at the center of a contact zone. However, the intermembrane distance for TAMs and integrins to engage their counter-receptors (~30 nm) is considerably larger than that of the immunoreceptors that are responsible for signaling during the establishment of the immunological synapse (~14 nm for the TcR/MHC class II and co-stimulatory receptors such as CD80/CD28). We would speculate that the organizing principles for immune and efferocytic synapses would be different due to the distinct requirements for signal propagation following cognate interaction of receptors. In an immune synapse, delivery of a signal that controls T cell proliferation or target cell killing requires maintenance of intercellular adhesion and redistribution of antigen-specific recognition molecules to the contact zone. By contrast, an efferocytic synapse would likely be a more dynamic structure that facilitates particle tethering and allows dynamic regulation of cytoskeletal organization as particle internalization proceeds. As discussed earlier, the localization of receptors involved in phagocytosis may involve initial tethering mediated by larger molecules as a prerequisite for engagement of smaller PtdSer binding receptors. The mechanisms for exclusion of phosphatases from an efferocytic synapse might also be distinct.

Finally, although phagocytosis of intact apoptotic targets is readily observed in vitro, the tight apposition of the plasma membranes of phagocytes and apoptotic targets in certain tissues in vivo may require a mechanistically distinct clearance process. For example, in the retina clearance of the outer segments of photoreceptors by retinal pigment epithelial cells has been likened to a phagocytic “pruning” of the photoreceptor outer segments (108). The molecular basis of removal of photoreceptor outer segments by retinal pigment epithelial cells involved Mer, Pros1 and Gas6, and the integrin αvβ5 (108–110). Electron microscopy analysis of retinal cell architecture reveals the exquisitely close contact between RPE cells and photoreceptors (111). Elegant in vivo imaging studies have revealed the diurnal exposure of PtdSer in localized a manner, which then triggers the “pinching off” of the distal tips of the photoreceptors by the adjacent RPE cells (112). The exposure of PtdSer on viable photoreceptors may have some parallels with a process termed phagoptosis (113) in which viable cells are recognized by phagocytes. However, during phagoptosis, recognition triggers apoptosis in the target cell (114). Although similar molecular pathways are involved in the recognition of PtdSer exposure on viable cells (e.g., MFG-E8, stabilins, αv integrins, and Mer) (115), the intercellular communication events that are involved are likely to be distinct from those required for efferocytosis.

In summary, the establishment of an efferocytic synapse may be required for efficient recognition of apoptotic cells by phagocytes. Cooperativity of receptor engagement may act to facilitate and stabilize adhesive interactions and lead to the assembly of signaling platforms that ultimately determine phagocyte responses to apoptotic cell binding and internalization.

Author Contributions

ID wrote the article and generated the figures. NB, JM, MV, and AR wrote the article and critically appraised the figures.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Funding

MV acknowledges funding from the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BB/M025160/1). AR is part funded by a UK Medical Research Council (MR/K013386/1). NB acknowledges funding from the EPSRC and MRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Optical Medical Imaging, OPTIMA (EP/L016559/1).

References

1. Persson C, Uller L. Transepithelial exit of leucocytes: inflicting, reflecting or resolving airway inflammation? Thorax (2010) 65:1111–5. doi:10.1136/thx.2009.133363

2. Poon IKH, Lucas CD, Rossi AG, Ravichandran KS. Apoptotic cell clearance: basic biology and therapeutic potential. Nat Rev Immunol (2014) 14:166–80. doi:10.1038/nri3607

3. Lauber K, Blumenthal SG, Waibel M, Wesselborg S. Clearance of apoptotic cells: getting rid of the corpses. Mol Cell (2004) 14:277–87. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00237-0

4. Savill J, Dransfield I, Gregory C, Haslett C. A blast from the past: clearance of apoptotic cells regulates immune responses. Nat Rev Immunol (2002) 2:965–75. doi:10.1038/nri957

5. Elliott MR, Ravichandran KS. Clearance of apoptotic cells: implications in health and disease. J Cell Biol (2010) 189:1059–70. doi:10.1083/jcb.201004096

6. Oldenborg PA, Gresham HD, Lindberg FP. CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPalpha) regulates Fcgamma and complement receptor-mediated phagocytosis. J Exp Med (2001) 193:855–62. doi:10.1084/jem.193.7.855

7. Kagan VE, Gleiss B, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Elenström-Magnusson C, Liu SX, et al. A role for oxidative stress in apoptosis: oxidation and externalization of phosphatidylserine is required for macrophage clearance of cells undergoing Fas-mediated apoptosis. J Immunol (2002) 169:487–99. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.487

8. Chang MK, Bergmark C, Laurila A, Hörkkö S, Han KH, Friedman P, et al. Monoclonal antibodies against oxidized low-density lipoprotein bind to apoptotic cells and inhibit their phagocytosis by elicited macrophages: evidence that oxidation-specific epitopes mediate macrophage recognition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1999) 96:6353–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.11.6353

9. Slater AF, Stefan C, Nobel I, van den Dobbelsteen DJ, Orrenius S. Signalling mechanisms and oxidative stress in apoptosis. Toxicol Lett (1995) 8(2–83):149–53. doi:10.1016/0378-4274(95)03474-9

10. Morris RG, Hargreaves AD, Duvall E, Wyllie AH. Hormone-induced cell death. 2. Surface changes in thymocytes undergoing apoptosis. Am J Pathol (1984) 115:426–36.

11. Franc NC, White K, Ezekowitz RA. Phagocytosis and development: back to the future. Curr Opin Immunol (1999) 11:47–52. doi:10.1016/S0952-7915(99)80009-0

12. Martin SJ, Reutelingsperger CP, McGahon AJ, Rader JA, van Schie RC, LaFace DM, et al. Early redistribution of plasma membrane phosphatidylserine is a general feature of apoptosis regardless of the initiating stimulus: inhibition by overexpression of Bcl-2 and Abl. J Exp Med (1995) 182:1545–56. doi:10.1084/jem.182.5.1545

13. Fadok VA, Savill JS, Haslett C, Bratton DL, Doherty DE, Campbell PA, et al. Different populations of macrophages use either the vitronectin receptor or the phosphatidylserine receptor to recognize and remove apoptotic cells. J Immunol (1992) 149:4029–35.

14. McEvoy L, Williamson P, Schlegel RA. Membrane phospholipid asymmetry as a determinant of erythrocyte recognition by macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1986) 83:3311–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.83.10.3311

15. Suzuki J, Denning DP, Imanishi E, Horvitz HR, Nagata S. Xk-related protein 8 and CED-8 promote phosphatidylserine exposure in apoptotic cells. Science (2013) 341:403–6. doi:10.1126/science.1236758

16. Yeung T, Gilbert GE, Shi J, Silvius J, Kapus A, Grinstein S. Membrane phosphatidylserine regulates surface charge and protein localization. Science (2008) 319:210–3. doi:10.1126/science.1152066

17. Park D, Tosello-Trampont AC, Elliott MR, Lu M, Haney LB, Ma Z, et al. BAI1 is an engulfment receptor for apoptotic cells upstream of the ELMO/Dock180/Rac module. Nature (2007) 450:430–4. doi:10.1038/nature06329

18. Park SY, Jung MY, Kim HJ, Lee SJ, Kim SY, Lee BH, et al. Rapid cell corpse clearance by stabilin-2, a membrane phosphatidylserine receptor. Cell Death Differ (2008) 15:192–201. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4402242

19. Wang X, Li W, Zhao D, Liu B, Shi Y, Chen B, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans transthyretin-like protein TTR-52 mediates recognition of apoptotic cells by the CED-1 phagocyte receptor. Nat Cell Biol (2010) 12:655–64. doi:10.1038/ncb2068

20. Andersen MH, Graversen H, Fedosov SN, Petersen TE, Rasmussen JT. Functional analyses of two cellular binding domains of bovine lactadherin. Biochemistry (Mosc) (2000) 39:6200–6. doi:10.1021/bi992221r

21. Hanayama R, Tanaka M, Miwa K, Shinohara A, Iwamatsu A, Nagata S. Identification of a factor that links apoptotic cells to phagocytes. Nature (2002) 417:182–7. doi:10.1038/417182a

22. Stitt TN, Conn G, Gore M, Lai C, Bruno J, Radziejewski C, et al. The anticoagulation factor protein S and its relative, Gas6, are ligands for the Tyro 3/Axl family of receptor tyrosine kinases. Cell (1995) 80:661–70.

23. Païdassi H, Tacnet-Delorme P, Garlatti V, Darnault C, Ghebrehiwet B, Gaboriaud C, et al. C1q binds phosphatidylserine and likely acts as a multiligand-bridging molecule in apoptotic cell recognition. J Immunol (2008) 180:2329–38. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2329

24. Bevers EM, Comfurius P, Zwaal RF. Changes in membrane phospholipid distribution during platelet activation. Biochim Biophys Acta (1983) 736:57–66. doi:10.1016/0005-2736(83)90169-4

25. Dillon SR, Mancini M, Rosen A, Schlissel MS. Annexin V binds to viable B cells and colocalizes with a marker of lipid rafts upon B cell receptor activation. J Immunol (2000) 164:1322–32. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.164.3.1322

26. Fischer K, Voelkl S, Berger J, Andreesen R, Pomorski T, Mackensen A. Antigen recognition induces phosphatidylserine exposure on the cell surface of human CD8+ T cells. Blood (2006) 108:4094–101. doi:10.1182/blood-2006-03-011742

27. Segawa K, Suzuki J, Nagata S. Constitutive exposure of phosphatidylserine on viable cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2011) 108:19246–51. doi:10.1073/pnas.1114799108

28. Tietjen GT, Gong Z, Chen CH, Vargas E, Crooks JE, Cao KD, et al. Molecular mechanism for differential recognition of membrane phosphatidylserine by the immune regulatory receptor Tim4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2014) 111:E1463–72. doi:10.1073/pnas.1320174111

29. Frasch SC, Berry KZ, Fernandez-Boyanapalli R, Jin HS, Leslie C, Henson PM, et al. NADPH oxidase-dependent generation of lysophosphatidylserine enhances clearance of activated and dying neutrophils via G2A. J Biol Chem (2008) 283:33736–49. doi:10.1074/jbc.M807047200

30. Tsai RK, Discher DE. Inhibition of ‘self’ engulfment through deactivation of myosin-II at the phagocytic synapse between human cells. J Cell Biol (2008) 180:989–1003. doi:10.1083/jcb.200708043

31. Gardai SJ, Bratton DL, Ogden CA, Henson PM. Recognition ligands on apoptotic cells: a perspective. J Leukoc Biol (2006) 79:896–903. doi:10.1189/jlb.1005550

32. Lawrence DW, King SB, Frazier WA, Koenig JM. Decreased CD47 expression during spontaneous apoptosis targets neutrophils for phagocytosis by monocyte-derived macrophages. Early Hum Dev (2009) 85:659–63. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.09.005

33. Lv Z, Bian Z, Shi L, Niu S, Ha B, Tremblay A, et al. Loss of cell surface CD47 clustering formation and binding avidity to SIRPα facilitate apoptotic cell clearance by macrophages. J Immunol (2015) 195:661–71. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1401719

34. Gardai SJ, Xiao YQ, Dickinson M, Nick JA, Voelker DR, Greene KE, et al. By binding SIRPalpha or calreticulin/CD91, lung collectins act as dual function surveillance molecules to suppress or enhance inflammation. Cell (2003) 115:13–23. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)00758-X

35. Savill JS, Henson PM, Haslett C. Phagocytosis of aged human neutrophils by macrophages is mediated by a novel ‘charge-sensitive’ recognition mechanism. J Clin Invest (1989) 84:1518–27. doi:10.1172/JCI114328

36. Ostrowski PP, Grinstein S, Freeman SA. Diffusion barriers, mechanical forces, and the biophysics of phagocytosis. Dev Cell (2016) 38:135–46. doi:10.1016/j.devcel.2016.06.023

37. Hart SP, Ross JA, Ross K, Haslett C, Dransfield I. Molecular characterization of the surface of apoptotic neutrophils: implications for functional downregulation and recognition by phagocytes. Cell Death Differ (2000) 7:493–503. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4400680

38. Franz S, Frey B, Sheriff A, Gaipl US, Beer A, Voll RE, et al. Lectins detect changes of the glycosylation status of plasma membrane constituents during late apoptosis. Cytometry A (2006) 69:230–9. doi:10.1002/cyto.a.20206

39. Meesmann HM, Fehr EM, Kierschke S, Herrmann M, Bilyy R, Heyder P, et al. Decrease of sialic acid residues as an eat-me signal on the surface of apoptotic lymphocytes. J Cell Sci (2010) 123:3347–56. doi:10.1242/jcs.066696

40. Jones J, Morgan BP. Apoptosis is associated with reduced expression of complement regulatory molecules, adhesion molecules and other receptors on polymorphonuclear leucocytes: functional relevance and role in inflammation. Immunology (1995) 86:651–60.

41. Takizawa F, Tsuji S, Nagasawa S. Enhancement of macrophage phagocytosis upon iC3b deposition on apoptotic cells. FEBS Lett (1996) 397:269–72. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(96)01197-0

42. Ogden CA, deCathelineau A, Hoffmann PR, Bratton D, Ghebrehiwet B, Fadok VA, et al. C1q and mannose binding lectin engagement of cell surface calreticulin and CD91 initiates macropinocytosis and uptake of apoptotic cells. J Exp Med (2001) 194:781–95. doi:10.1084/jem.194.6.781

43. Arur S, Uche UE, Rezaul K, Fong M, Scranton V, Cowan AE, et al. Annexin I is an endogenous ligand that mediates apoptotic cell engulfment. Dev Cell (2003) 4:587–98. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(03)00090-X

44. Uehara H, Shacter E. Auto-oxidation and oligomerization of protein S on the apoptotic cell surface is required for Mer tyrosine kinase-mediated phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. J Immunol (2008) 180:2522–30. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2522

45. Hart SP, Alexander KM, Dransfield I. Immune complexes bind preferentially to Fc gamma RIIA (CD32) on apoptotic neutrophils, leading to augmented phagocytosis by macrophages and release of proinflammatory cytokines. J Immunol (2004) 172:1882–7. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.172.3.1882

46. Dransfield I, Buckle AM, Savill JS, McDowall A, Haslett C, Hogg N. Neutrophil apoptosis is associated with a reduction in CD16 (Fc gamma RIII) expression. J Immunol (1994) 153:1254–63.

47. Dransfield I, Stocks SC, Haslett C. Regulation of cell adhesion molecule expression and function associated with neutrophil apoptosis. Blood (1995) 85:3264–73.

48. Nishimori H, Shiratsuchi T, Urano T, Kimura Y, Kiyono K, Tatsumi K, et al. A novel brain-specific p53-target gene, BAI1, containing thrombospondin type 1 repeats inhibits experimental angiogenesis. Oncogene (1997) 15:2145–50. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201542

49. Tosello-Trampont AC, Kinchen JM, Brugnera E, Haney LB, Hengartner MO, Ravichandran KS. Identification of two signaling submodules within the CrkII/ELMO/Dock180 pathway regulating engulfment of apoptotic cells. Cell Death Differ (2007) 14:963–72. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4402094

50. Penberthy KK, Ravichandran KS. Apoptotic cell recognition receptors and scavenger receptors. Immunol Rev (2016) 269:44–59. doi:10.1111/imr.12376

51. Borrego F. The CD300 molecules: an emerging family of regulators of the immune system. Blood (2013) 121:1951–60. doi:10.1182/blood-2012-09-435057

52. Murakami Y, Tian L, Voss OH, Margulies DH, Krzewski K, Coligan JE. CD300b regulates the phagocytosis of apoptotic cells via phosphatidylserine recognition. Cell Death Differ (2014) 21:1746–57. doi:10.1038/cdd.2014.86

53. Park SY, Kang KB, Thapa N, Kim SY, Lee SJ, Kim IS. Requirement of adaptor protein GULP during stabilin-2-mediated cell corpse engulfment. J Biol Chem (2008) 283:10593–600. doi:10.1074/jbc.M709105200

54. Su HP, Nakada-Tsukui K, Tosello-Trampont AC, Li Y, Bu G, Henson PM, et al. Interaction of CED-6/GULP, an adapter protein involved in engulfment of apoptotic cells with CED-1 and CD91/low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein (LRP). J Biol Chem (2002) 277:11772–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M109336200

55. Park D, Hochreiter-Hufford A, Ravichandran KS. The phosphatidylserine receptor TIM-4 does not mediate direct signaling. Curr Biol (2009) 19(4):346–51. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.01.042

56. Lemke G. Biology of the TAM receptors. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2013) 5:a009076. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a009076

57. Savill J, Dransfield I, Hogg N, Haslett C. Vitronectin receptor-mediated phagocytosis of cells undergoing apoptosis. Nature (1990) 343:170–3. doi:10.1038/343170a0

58. Savill J, Hogg N, Ren Y, Haslett C. Thrombospondin cooperates with CD36 and the vitronectin receptor in macrophage recognition of neutrophils undergoing apoptosis. J Clin Invest (1992) 90:1513–22. doi:10.1172/JCI116019

59. Rabinovitch M. The dissociation of the attachment and ingestion phases of phagocytosis by macrophages. Exp Cell Res (1967) 46:19–28. doi:10.1016/0014-4827(67)90405-3

60. Griffin FM, Griffin JA, Leider JE, Silverstein SC. Studies on the mechanism of phagocytosis. I. Requirements for circumferential attachment of particle-bound ligands to specific receptors on the macrophage plasma membrane. J Exp Med (1975) 142:1263–82. doi:10.1084/jem.142.5.1263

61. Dransfield I, Zagórska A, Lew ED, Michail K, Lemke G. Mer receptor tyrosine kinase mediates both tethering and phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. Cell Death Dis (2015) 6:e1646. doi:10.1038/cddis.2015.18

62. Griffin FM, Mullinax PJ. Effects of differentiation in vivo and of lymphokine treatment in vitro on the mobility of C3 receptors of human and mouse mononuclear phagocytes. J Immunol (1985) 135:3394–7.

63. Segal G, Lee W, Arora PD, McKee M, Downey G, McCulloch CA. Involvement of actin filaments and integrins in the binding step in collagen phagocytosis by human fibroblasts. J Cell Sci (2001) 114:119–29.

64. Freeman SA, Grinstein S. Phagocytosis: receptors, signal integration, and the cytoskeleton. Immunol Rev (2014) 262:193–215. doi:10.1111/imr.12212

65. Hart SP, Rossi AG, Haslett C, Dransfield I. Characterization of the effects of cross-linking of macrophage CD44 associated with increased phagocytosis of apoptotic PMN. PLoS One (2012) 7:e33142. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0033142

66. Hart SP, Dougherty GJ, Haslett C, Dransfield I. CD44 regulates phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophil granulocytes, but not apoptotic lymphocytes, by human macrophages. J Immunol (1997) 159:919–25.

67. Flannagan RS, Harrison RE, Yip CM, Jaqaman K, Grinstein S. Dynamic macrophage ‘probing’ is required for the efficient capture of phagocytic targets. J Cell Biol (2010) 191:1205–18. doi:10.1083/jcb.201007056

68. Niedergang F, Di Bartolo V, Alcover A. Comparative anatomy of phagocytic and immunological synapses. Front Immunol (2016) 7:18. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2016.00018

69. Kayalar C, Ord T, Testa MP, Zhong LT, Bredesen DE. Cleavage of actin by interleukin 1 beta-converting enzyme to reverse DNase I inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1996) 93:2234–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.5.2234

70. Concha NO, Head JF, Kaetzel MA, Dedman JR, Seaton BA. Annexin V forms calcium-dependent trimeric units on phospholipid vesicles. FEBS Lett (1992) 314:159–62. doi:10.1016/0014-5793(92)80964-I

71. van Genderen HO, Kenis H, Hofstra L, Narula J, Reutelingsperger CPM. Extracellular annexin A5: functions of phosphatidylserine-binding and two-dimensional crystallization. Biochim Biophys Acta (2008) 1783:953–63. doi:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.01.030

72. Grakoui A, Bromley SK, Sumen C, Davis MM, Shaw AS, Allen PM, et al. The immunological synapse: a molecular machine controlling T cell activation. Science (1999) 285:221–7. doi:10.1126/science.285.5425.221

73. Dustin ML, Chakraborty AK, Shaw AS. Understanding the structure and function of the immunological synapse. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2010) 2:a002311. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a002311

74. Dustin ML, Groves JT. Receptor signaling clusters in the immune synapse. Annu Rev Biophys (2012) 41:543–56. doi:10.1146/annurev-biophys-042910-155238

75. Lopes FB, Bálint Š, Valvo S, Felce JH, Hessel EM, Dustin ML, et al. Membrane nanoclusters of FcγRI segregate from inhibitory SIRPα upon activation of human macrophages. J Cell Biol (2017) 216:1123–41. doi:10.1083/jcb.201608094

76. Lin J, Kurilova S, Scott BL, Bosworth E, Iverson BE, Bailey EM, et al. TIRF imaging of Fc gamma receptor microclusters dynamics and signaling on macrophages during frustrated phagocytosis. BMC Immunol (2016) 17:5. doi:10.1186/s12865-016-0143-2

77. Leupin O, Zaru R, Laroche T, Müller S, Valitutti S. Exclusion of CD45 from the T-cell receptor signaling area in antigen-stimulated T lymphocytes. Curr Biol (2000) 10:277–80. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(00)00362-6

78. Goodridge HS, Reyes CN, Becker CA, Katsumoto TR, Ma J, Wolf AJ, et al. Activation of the innate immune receptor dectin-1 upon formation of a ‘phagocytic synapse’. Nature (2011) 472:471–5. doi:10.1038/nature10071

79. Freeman SA, Goyette J, Furuya W, Woods EC, Bertozzi CR, Bergmeier W, et al. Integrins form an expanding diffusional barrier that coordinates phagocytosis. Cell (2016) 164:128–40. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.048

80. Elliott MR, Koster KM, Murphy PS. Efferocytosis signaling in the regulation of macrophage inflammatory responses. J Immunol (2017) 198:1387–94. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.1601520

81. Chang VT, Fernandes RA, Ganzinger KA, Lee SF, Siebold C, McColl J, et al. Initiation of T cell signaling by CD45 segregation at ‘close contacts’. Nat Immunol (2016) 17:574–82. doi:10.1038/ni.3392

82. Flannagan RS, Canton J, Furuya W, Glogauer M, Grinstein S. The phosphatidylserine receptor TIM4 utilizes integrins as coreceptors to effect phagocytosis. Mol Biol Cell (2014) 25:1511–22. doi:10.1091/mbc.E13-04-0212

83. Kim S, Park SY, Kim SY, Bae DJ, Pyo JH, Hong M, et al. Cross talk between engulfment receptors stabilin-2 and integrin αvβ5 orchestrates engulfment of phosphatidylserine-exposed erythrocytes. Mol Cell Biol (2012) 32:2698–708. doi:10.1128/MCB.06743-11

84. Wu Y, Singh S, Georgescu M-M, Birge RB. A role for Mer tyrosine kinase in alphavbeta5 integrin-mediated phagocytosis of apoptotic cells. J Cell Sci (2005) 118:539–53. doi:10.1242/jcs.01632

85. Vernon-Wilson EF, Auradé F, Brown SB. CD31 promotes beta1 integrin-dependent engulfment of apoptotic Jurkat T lymphocytes opsonized for phagocytosis by fibronectin. J Leukoc Biol (2006) 79:1260–7. doi:10.1189/jlb.1005571

86. McCutcheon JC, Hart SP, Canning M, Ross K, Humphries MJ, Dransfield I. Regulation of macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils by adhesion to fibronectin. J Leukoc Biol (1998) 64:600–7.

87. Kirkham PA, Spooner G, Rahman I, Rossi AG. Macrophage phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils is compromised by matrix proteins modified by cigarette smoke and lipid peroxidation products. Biochem Biophys Res Commun (2004) 318:32–7. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.04.003

88. Barclay AN, Van den Berg TK. The interaction between signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPα) and CD47: structure, function, and therapeutic target. Annu Rev Immunol (2014) 32:25–50. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-032713-120142

89. Lillemeier BF, Mörtelmaier MA, Forstner MB, Huppa JB, Groves JT, Davis MM. TCR and Lat are expressed on separate protein islands on T cell membranes and concatenate during activation. Nat Immunol (2009) 11:90–6. doi:10.1038/ni.1832

90. Araç D, Boucard AA, Bolliger MF, Nguyen J, Soltis SM, Südhof TC, et al. A novel evolutionarily conserved domain of cell-adhesion GPCRs mediates autoproteolysis. EMBO J (2012) 31:1364–78. doi:10.1038/emboj.2012.26

91. Campbell ID, Humphries MJ. Integrin structure, activation, and interactions. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol (2011) 3:A004994. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a004994

92. Xiong JP, Stehle T, Diefenbach B, Zhang R, Dunker R, Scott DL, et al. Crystal structure of the extracellular segment of integrin alpha Vbeta3. Science (2001) 294:339–45. doi:10.1126/science.1064535

93. Chattopadhyay K, Lazar-Molnar E, Yan Q, Rubinstein R, Zhan C, Vigdorovich V, et al. Sequence, structure, function, immunity: structural genomics of costimulation. Immunol Rev (2009) 229:356–86. doi:10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00778.x

94. Dahlbäck B, Smith CA, Müller-Eberhard HJ. Visualization of human C4b-binding protein and its complexes with vitamin K-dependent protein S and complement protein C4b. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1983) 80:3461–5. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.11.3461

95. Heiring C, Dahlbäck B, Muller YA. Ligand recognition and homophilic interactions in Tyro3: structural insights into the Axl/Tyro3 receptor tyrosine kinase family. J Biol Chem (2004) 279:6952–8. doi:10.1074/jbc.M311750200

96. Pratt KP, Shen BW, Takeshima K, Davie EW, Fujikawa K, Stoddard BL. Structure of the C2 domain of human factor VIII at 1.5 A resolution. Nature (1999) 402:439–42. doi:10.1038/46601

97. Rudenko G, Henry L, Henderson K, Ichtchenko K, Brown MS, Goldstein JL, et al. Structure of the LDL receptor extracellular domain at endosomal pH. Science (2002) 298:2353–8. doi:10.1126/science.1078124

98. Cao E, Zang X, Ramagopal UA, Mukhopadhaya A, Fedorov A, Fedorov E, et al. T cell immunoglobulin mucin-3 crystal structure reveals a galectin-9-independent ligand-binding surface. Immunity (2007) 26:311–21. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.016

99. Cooke RM, Wilkinson AJ, Baron M, Pastore A, Tappin MJ, Campbell ID, et al. The solution structure of human epidermal growth factor. Nature (1987) 327:339–41. doi:10.1038/327339a0

100. Ellgaard L, Frickel E-M. Calnexin, calreticulin, and ERp57: teammates in glycoprotein folding. Cell Biochem Biophys (2003) 39:223–47. doi:10.1385/CBB:39:3:223

101. Leahy DJ, Aukhil I, Erickson HP. 2.0 A crystal structure of a four-domain segment of human fibronectin encompassing the RGD loop and synergy region. Cell (1996) 84:155–64. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81002-8

102. Lillis AP, Van Duyn LB, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Strickland DK. LDL receptor-related protein 1: unique tissue-specific functions revealed by selective gene knockout studies. Physiol Rev (2008) 88:887–918. doi:10.1152/physrev.00033.2007

103. Pike AC, Brzozowski AM, Roberts SM, Olsen OH, Persson E. Structure of human factor VIIa and its implications for the triggering of blood coagulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1999) 96:8925–30. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.16.8925

104. Tan K, Duquette M, Liu JH, Dong Y, Zhang R, Joachimiak A, et al. Crystal structure of the TSP-1 type 1 repeats: a novel layered fold and its biological implication. J Cell Biol (2002) 159:373–82. doi:10.1083/jcb.200206062

105. Sasaki T, Knyazev PG, Clout NJ, Cheburkin Y, Göhring W, Ullrich A, et al. Structural basis for Gas6-Axl signalling. EMBO J (2006) 25:80–7. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600912

106. Langenhan T, Piao X, Monk KR. Adhesion G protein-coupled receptors in nervous system development and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci (2016) 17:550–61. doi:10.1038/nrn.2016.86

107. Ramirez-Ortiz ZG, Pendergraft WF III, Prasad A, Byrne MH, Iram T, Blanchette CJ, et al. The scavenger receptor SCARF1 mediates the clearance of apoptotic cells and prevents autoimmunity. Nat Immunol (2013) 14:917–26. doi:10.1038/ni.2670

108. Burstyn-Cohen T, Lew ED, Través PG, Burrola PG, Hash JC, Lemke G. Genetic dissection of TAM receptor-ligand interaction in retinal pigment epithelial cell phagocytosis. Neuron (2012) 76:1123–32. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.015

109. Finnemann SC. Role of alphavbeta5 integrin in regulating phagocytosis by the retinal pigment epithelium. Adv Exp Med Biol (2003) 533:337–42. doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-0067-4_42

110. Finnemann SC, Bonilha VL, Marmorstein AD, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Phagocytosis of rod outer segments by retinal pigment epithelial cells requires alpha(v)beta5 integrin for binding but not for internalization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (1997) 94:12932–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.24.12932

111. Kevany BM, Palczewski K. Phagocytosis of retinal rod and cone photoreceptors. Physiology (Bethesda) (2010) 25:8–15. doi:10.1152/physiol.00038.2009

112. Ruggiero L, Connor MP, Chen J, Langen R, Finnemann SC. Diurnal, localized exposure of phosphatidylserine by rod outer segment tips in wild-type but not Itgb5-/- or Mfge8-/- mouse retina. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A (2012) 109:8145–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.1121101109

113. Fricker M, Oliva-Martín MJ, Brown GC. Primary phagocytosis of viable neurons by microglia activated with LPS or Aβ is dependent on calreticulin/LRP phagocytic signalling. J Neuroinflammation (2012) 9:196. doi:10.1186/1742-2094-9-196

114. Hornik TC, Vilalta A, Brown GC. Activated microglia cause reversible apoptosis of pheochromocytoma cells, inducing their cell death by phagocytosis. J Cell Sci (2016) 129:65–79. doi:10.1242/jcs.174631

Keywords: macrophage, phagocytosis, apoptotic cells, cell–cell interactions, phagocytic receptor, phosphatidylserine, opsonin

Citation: Barth ND, Marwick JA, Vendrell M, Rossi AG and Dransfield I (2017) The “Phagocytic Synapse” and Clearance of Apoptotic Cells. Front. Immunol. 8:1708. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01708

Received: 28 August 2017; Accepted: 20 November 2017;

Published: 04 December 2017

Edited by:

Kirsten Lauber, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, GermanyReviewed by:

Raymond B. Birge, Rutgers University, The State University of New Jersey, United StatesMichael R. Elliott, University of Rochester, United States

Copyright: © 2017 Barth, Marwick, Vendrell, Rossi and Dransfield. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ian Dransfield, i.dransfield@ed.ac.uk

Nicole D. Barth

Nicole D. Barth John A. Marwick

John A. Marwick Marc Vendrell

Marc Vendrell Adriano G. Rossi

Adriano G. Rossi Ian Dransfield

Ian Dransfield