Social Innovation in Community Energy in Europe: A Review of the Evidence

- 1Information and Computational Sciences (ICS), The James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen, United Kingdom

- 2Social, Economic and Geographical Sciences (SEGS), The James Hutton Institute, Aberdeen, United Kingdom

- 3Bavarian School of Public Policy, Technical University Munich, Munich, Germany

- 4Renewables Grid Initiative, Berlin, Germany

- 5Climate Service Center Germany (GERICS), Hamburg, Germany

- 6Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), Member of the Leibniz Association, Potsdam, Germany

- 7The Rural Development Company Alford, Aberdeenshire, United Kingdom

Citizen-driven Renewable Energy (RE) projects of various kinds, known collectively as community energy (CE), have an important part to play in the worldwide transition to cleaner energy systems. On the basis of evidence from 8 European countries, we investigate CE, over approximately the last 50 years (c.1970–2018), through the lens of Social Innovation (SI). We carry out a detailed review of literature around the social dimension of renewable energy; we collect, describe and map CE initiatives from Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and the UK; and we unpack the SI concept into 4 operational criteria which we suggest are essential to recognizing SI in CE. These are: (1) Crises and opportunities; (2) the agency of civil society; (3) reconfiguration of social practices, institutions and networks; (4) new ways of working. We identify three main phases of SI in CE. The environmental movements of the 1960s and the “oil shocks” of the 1970s provided the catalyst for a series of innovative societal responses around energy and self-sufficiency. A second wave of SI relates to the mainstreaming of RE and associated government support mechanisms. In this phase, with some important exceptions, successful CE initiatives were mainly confined to those countries where they were already embedded as innovators in the previous phase. The third phase of CE innovation relates to the societal response to the Great Recession that began in 2008 and lasted most of the subsequent decade. CE initiatives formed around this time were also strongly focused around democratization of energy and citizen empowerment in the context of rising energy prices, a weak economy, and a production and supply system dominated by excessively powerful multinational energy firms. CE initiatives today are more diverse than at any time previously, and are likely to continue to act as incubators for pioneering initiatives addressing virtually all aspects of energy. However, large multinational energy firms remain the dominant vehicle for delivery of the energy transition, and the apparent excitement in European policy circles for “community energy” does not extend to democratization of energy or genuine empowerment of citizens.

Introduction

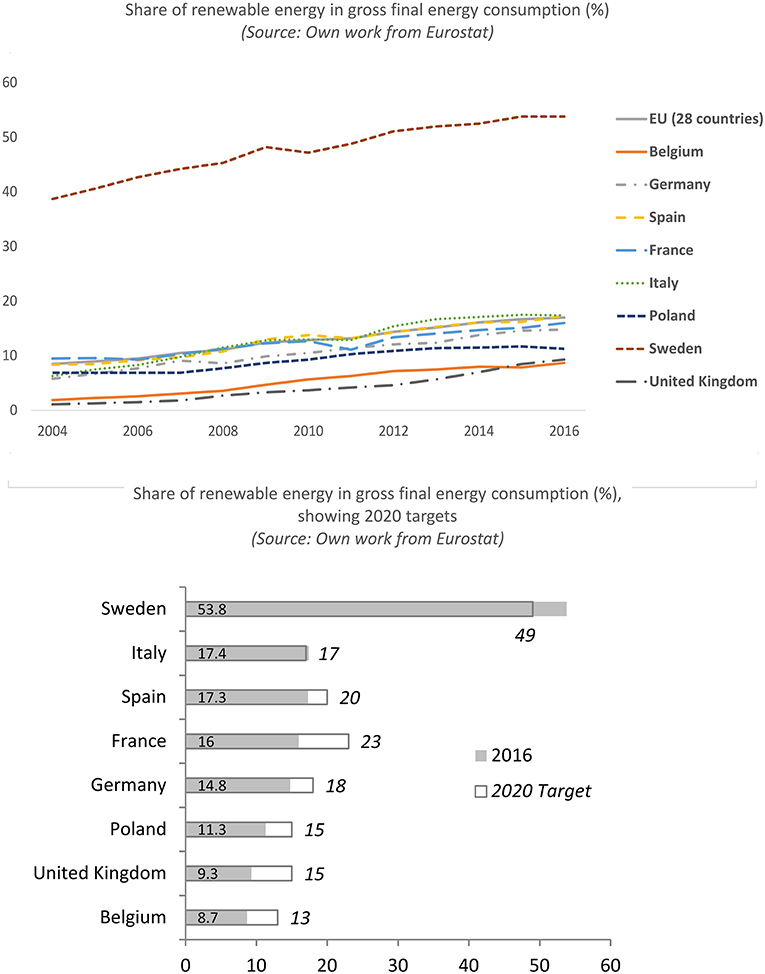

With the goals of the Paris climate agreement looking difficult to achieve (e.g., Kriegler et al., 2018; Larkin et al., 2018), and Europe's efforts to increase the proportion of RE in its energy systems only partially successful (Figure 1), new approaches to the clean energy transition are needed. This necessity, together with citizens' growing interest in sustainability and energy democracy (Szulecki, 2018) offers both a clear motivation and opportunity for communities to address both concerns together by forging a new relationship with energy. In this context, a wide range of community-led sustainable energy projects (CE) are currently being implemented all around the world. European countries are at the forefront of this emerging trend. CE is found in diverse forms throughout Europe, including wind turbines and solar farms in cooperative ownership that return profits to local investors, mini-hydro-electricity schemes which power local homes and businesses, farmer's bioenergy collectives, church, or community center renewable heat initiatives, locally-owned energy distribution networks and “eco-villages” which promote self-sufficiency, zero-waste and energy efficiency. The common denominator that binds these diverse projects together is that all, in some form or other, emphasize citizen participation around the common issue of energy.

In this sense, the concept of social innovation (SI) is relevant. SI refers to the reconfiguring of social practices in response to societal challenges, with the aim of improving societal well-being through the engagement of civil society actors (Polman et al., 2017). It is this focus on civil society engagement that links CE to SI—as an innovation in energy that emphasizes community participation, CE is clearly a form of SI.

In fact, SI has been instrumental in citizen-based activity associated with reducing emissions or increasing renewable energy production (Harnmeijer et al., 2018). At present, however, SI is still a contested concept. In 2013 a European Commission document (European Commission, 2013) felt unable to offer a precise definition. MacCallum et al. (2009) see reconfiguration of social practices, institutions and networks as key elements of social innovation where civil society agency creates new ways of responding to crises and opportunities. We concur with this conceptualization, which is broadly matched by later commentators (Cajaiba-Santana, 2014). Social innovation, in their view, “rejects the traditional, technology-focused application of the term “innovation”…in favor of a more nuanced reading which valorizes the knowledge and cultural assets of communities and which foregrounds the creative reconfiguration of social relations” ( MacCallum et al. (2009: 1–2). In this sense, the accelerating impacts of climate change and ongoing struggle to transition to lower-carbon forms of energy is clearly an outstanding opportunity to transform societal approaches to energy itself. For example, diversifying beyond fossil fuels opens energy production to a wider group of stakeholders beyond traditional oil majors; at the same time, decentralized energy generation offers an opportunity for consumers to offer demand-management services through their homes and devices. In effect, new opportunities have emerged for citizens to become active partners in the management of energy as a resource, rather than passive “consumers” of energy as a commodity.

It is this idea of “creative reconfiguration of social relations” around energy—innovation in forms of governance, institutions and actor relationships—that underlies the concept of CE. Thus, while CE is rarely described as social innovation, it seems to sit comfortably within the definitions of social innovation offered by Cajaiba-Santana and others.

Yet strategic approaches to energy transition currently being advanced by European policy-makers remain firmly anchored to this earlier “technology focused” innovation paradigm, and do not seriously contemplate any form of genuine reconfiguration, or “new social contract for energy.” This leads us to wonder to what extent the phenomenon of CE, which has a large and growing literature, and, in some countries, a degree of government support, might offer potential to bring about real change in the relationship between society, and energy Europe-wide. In this paper, we strive to answer this question by examining CE in Europe through the lens of SI. To this end, we define two Research Objectives (ROs), as follows:

RO1: Develop a greater understanding of what constitutes CE in Europe by reviewing relevant literature and collecting evidence for CE initiatives from primary sources for a range of European countries.

To understand SI in CE in Europe, we must first understand CE. While there is a large and growing literature on CE itself, a broad review of its form and extent across Europe is generally lacking. There is a pressing need to map, characterize, and investigate the range of CE initiatives across Europe, in order to better understand the circumstances that lead to high levels of development. While several projects, like the EU-funded REScoop project (Vansintjan, 2015) or the Energy Archipelago (Harnmeijer et al., 2012) have already begun to address this need, the scientific literature remains somewhat disconnected from the extensive publicly available information on individual CE initiatives found in gray literature, news reports and community websites. At the same time, the literature is generally focused on CE in pioneering countries like Germany and Denmark with few studies of the phenomenon in Southern Europe (Candelise and Ruggieri, 2017; Heras-Saizarbitoria et al., 2018), or the former communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe (Holstenkamp, 2018).

RO2: Apply social innovation criteria based on literature review and data collection exercise as a framework for analysis of the CE phenomenon in our case study countries.

While SI clearly provides a useful conceptual framework for the study of CE, there are few studies that do this directly. To fill this research gap is important for two key reasons. Firstly, while broadly supportive statements about CE can be found on European Commission sponsored websites (e.g., https://climatepolicyinfohub.eu/community-energy-projects-europes-pioneering-task), it is unclear to what extent meaningful community participation is actually a significant feature of mainstream renewable energy developments in Europe today; SI, as we have explained, offers an ideal framework for investigating this. Secondly, SI, at least superficially, seems to be a focus of current European policy (see e.g., https://ec.europa.eu/growth/industry/innovation/policy/social_en). Despite this apparent enthusiasm, it is unclear what, if anything, European governments are doing to promote the transformation of ownership, control and civil society participation in energy that recent definitions of SI clearly imply. By unpicking these recent definitions and applying them to CE examples uncovered by our survey (RO 1), we hope to shed light on these questions.

Methods

To address the ROs defined above, we followed a stepwise methodology comprising 3 key stages:

1. Literature review of key themes around the social dimension of CE. Our review was intended to be exploratory rather than exhaustive. We did not seek to systematically identify all relevant literature, rather we aimed to characterize key tendencies chronologically and demonstrate how our interest in SI relates to the emerging interest in the social dimension of energy.

2. Internet search and mapping exercise of CE initiatives in 8 countries across the European continent (RO1), comprising Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom. Though the survey presented does not claim to be comprehensive, its broad scope means that it is likely to be representative of CE in Europe generally. Case study countries were chosen with the aim of providing as diverse a sample as possible of different European approaches to energy taking in a broad range of energy types, energy dependencies, institutional forms, and social, and political cultures. Our study area thus includes Europe's largest economies (Germany, United Kingdom, France, and Italy) in the heart of Europe, and countries on its southern, northern and eastern borders. The study encompasses countries with traditionally very high external energy dependence (Italy, Belgium and Spain), carbon-intensive economies whose external energy dependence is increasing from historically low levels (Poland, Germany, and the United Kingdom) and countries whose energy dependence is decreasing (France, Sweden). In terms of energy, we include countries with high capacity in solar (Germany, Spain, Italy), wind (Germany, UK, Spain) and Hydropower (Sweden, France, Italy) and countries where renewables are in general less developed (Poland). We include strongly nuclear energy-dependent countries like the UK and France (and increasingly, Sweden) as well as denuclearizing Germany and countries where nuclear power is historically small and unpopular (Spain) or not present at all (Poland). We include “large state” countries like Germany, Sweden and the UK, where governance is highly centralized, and countries where governance is highly devolved to regions and municipalities (Italy, Spain). Both East Germany and Poland are former command economies, where the legacy of communism has left deep roots in civil society.

Data were compiled by individual team members with specific expertise in the chosen case study countries from a wide range of published and unpublished sources to produce a database of initiatives. These were mapped by a dedicated cartographer, and cross-checked by the lead author, who then returned to the team to request additions and amendments during the analysis stage (3; below).

The work is exploratory in nature, and we have therefore tried to let a picture emerge from the data rather than imposing a top-down blueprint of what CE is or should be. Our search thus includes any energy-related initiative that is small-scale or emanating from non-conventional institutional forms of generation and supply, whether it is citizen, local government, small business, NGO-led, or some combination of these, provided that it involves some degree of citizen control or participation. Our initial conceptualization of CE is thus closer to the very broad definition of Magnani and Osti (2016) as “a variety of experiences of renewable energy development and provision characterized by various degrees of public participation in project development” than that of Walker and Devine-Wright (2008) or Seyfang et al. (2013) who emphasize strong and meaningful local involvement and control. By casting the net wide, we seek to obtain a representative picture of what CE is, rather than what it ideally should be.

3. Analysis and discussion of results from stage 2, in the light of literature identified in stage 1. Following the definitions given earlier, (e.g., MacCallum et al., 2009; Cajaiba-Santana, 2014) 4 key criteria can be identified as instrumental for recognizing social innovation: (1) Crises and opportunities; (2) the agency of civil society; (3) reconfiguration of social practices, institutions and networks; (4) new ways of working that successfully emerge from such a reconfiguration. To address RO2, we apply these 4 SI criteria as a framework for analysis of the CE phenomenon in our case study countries.

In the final part of this paper, we discuss the lessons learnt from the results obtained, and offer some hypotheses and questions for future research in SI and CE.

Literature Review of Key Themes

Community Energy

CE is found in diverse legal, organizational and financial forms (Walker, 2008; Rae and Bradley, 2012; Holstenkamp, 2018), and may involve participation in project development (process), and/or sharing collective benefits (outcomes) (Walker and Devine-Wright, 2008). CE initiatives may comprise communities of place—emphasizing shared values associated with a particular territory or landscape—or communities of practice—emphasizing shared ethics and world views, financial circumstances or problems (Magnani and Osti, 2016; but see also Becker and Kunze, 2014) Energy cooperatives (REScoops) are the oldest, and perhaps best known, type of CE; these may be either energy producers, suppliers, or both (Capellán-Pérez et al., 2016; Magnani and Osti, 2016), and provide energy or revenue from sales to their members, who are not necessarily part of the same geographical community. Other types of initiatives include community development companies or not-for-profit organizations who manage production or supply for direct local benefit (Slee and Harnmeijer, 2017; Harnmeijer et al., 2018), and sustainability movements of various sorts ranging from substantial and well-organized transition towns initiatives (Seyfang and Haxeltine, 2012) to eco-villages and informal citizen's groups emphasizing self-sufficiency and energy saving (Georg, 1999; Zhu et al., 2015; Renau, 2018). However, as Creamer et al. (2018) have observed, CE refers to a broad spectrum of energy-related initiatives, not a specific class of project. Though often considered to be sustainable, democratic, decentralized, grassroots, cooperative and local, many CE projects may address only one of these aspects. In fact, engaging with such a complex emerging phenomenon is a non-trivial task, which the energy research community is just beginning to address.

Social Innovation in Community Energy

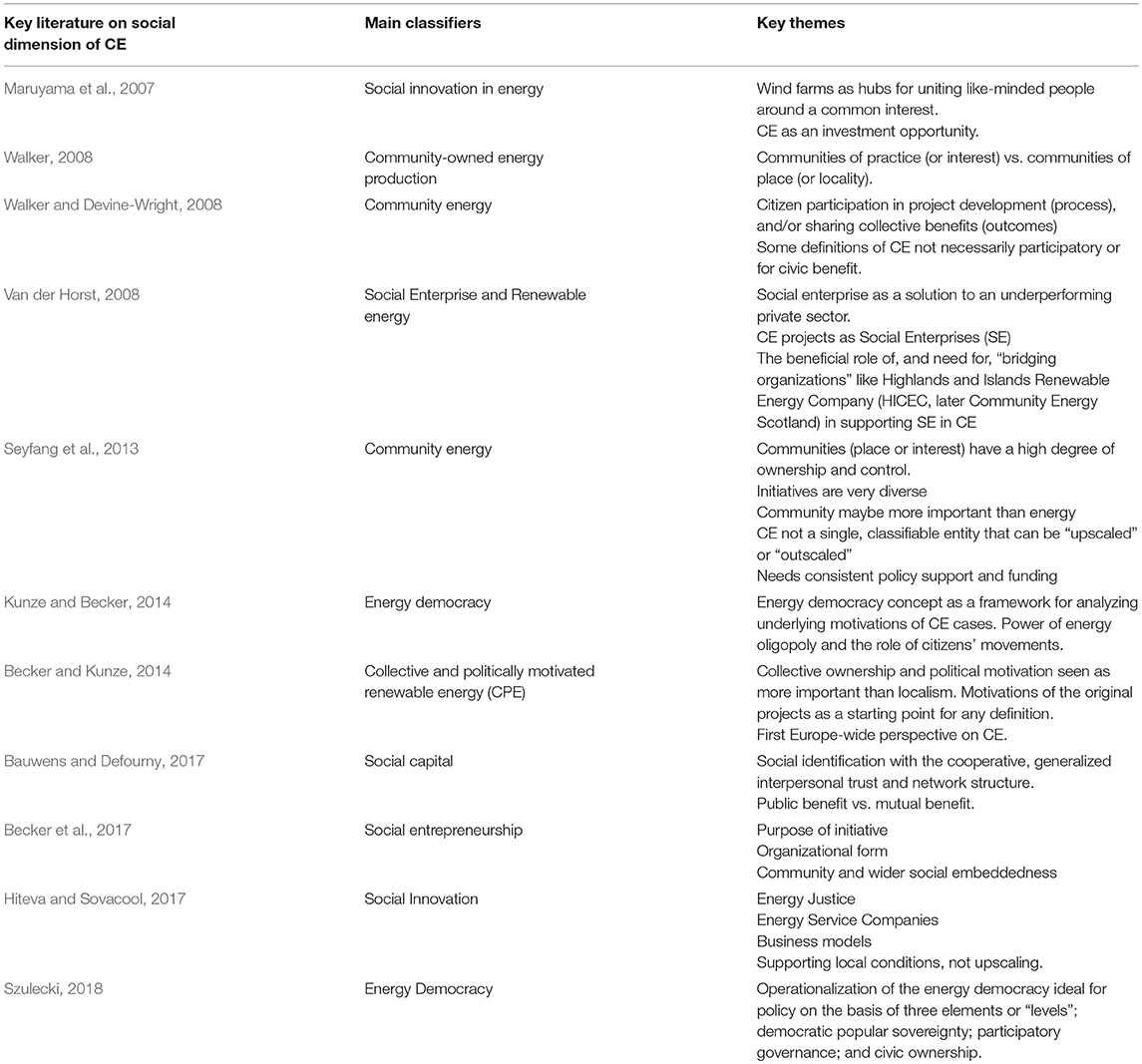

The social dimension of renewable energy has a large and growing literature (Table A1), which has traditionally been strongly dominated by UK based researchers and case studies, though this is now beginning to change (see e.g., Pepermans and Loots, 2013; Becker and Kunze, 2014; Magnani and Osti, 2016; Bauwens and Defourny, 2017; Szulecki, 2018 etc.). As a separate research strand, it has its roots in research around the social acceptance of large energy projects like wind farms. These were extensively deployed in a centralized fashion across most of Europe during the 1990s usually with minimal consultation or meaningful citizen participation, in many cases leading to rejection by local people (see e.g., Wolsink, 1994, 2000; Devine-Wright, 2005; Aitken, 2010). Unsurprisingly, several studies have found that where benefits accrue to the community as a whole, public acceptance is likely to be greater (Rogers et al., 2008; Warren and McFadyen, 2010).

Maruyama et al. (2007), in a study of community participation in wind energy schemes in Japan, employ the term social innovation to refer to a new system of social dynamics which changes the rules of risk–benefit distribution and the role of social actors around a new technology, in this case, wind energy. While the Japanese wind energy cooperatives explored in this paper were investment opportunities, rather than locally based development ventures, they also served as hubs for uniting like-minded people around a public goods issue (protecting the environment). Thus the potential dilution of place and community identity in these schemes is compensated for by the strengthening of networks around shared environmental values.

While Walker et al. (2007) regard the emergence of “community-based localism” around renewable energy in the UK in the early and mid-2000s as a positive development, they also caution that the often loose definitions of community, e.g., as a group of buildings or a legal entity with a not-for-profit status, do not necessarily imply “participation, empowerment or wider civic outcome” (Hoffman and High-Pippert, 2005; Walker et al., 2007). Van der Horst (2008) provides a broadly contemporary study of CE, which he refers to as social enterprise in renewable energy. The emergence of this phenomenon in the UK is attributed by this author to the slow progress of the private sector in developing renewable energy, together with the opportunities that it provided to support rural communities at risk of fuel poverty due to their remote locations, especially in Scotland. Other authors concur that Scotland has been a significant focus of CE innovation, effectively using CE as a tool for rural development (Slee and Harnmeijer, 2017; van Veelen, 2017).

The enormous growth in CE in the UK at this time is evidenced by a series of detailed case studies of individual CE projects (Hargreaves et al., 2013; Seyfang et al., 2013, 2014; Grassroots Innovations, 2018). In this research, CE initiatives are revealed as a patchwork of grassroots movements of extremely diverse kinds, not easily reducible to a single model entity or process, and likely not amenable to one-size-fits-all policy solutions (Rae and Bradley, 2012; Seyfang et al., 2013). This pluralistic nature of CE has given rise to debate in the academic literature (e.g., van Veelen, 2017) over the relevance of dominant transitions research approaches like the multi-level perspective (Geels, 2002) and the related theory of socio-technical niches (e.g., Kemp et al., 1998). These approaches have been criticized for their tendency to treat community energy as a homogenous phenomenon (e.g., Seyfang et al., 2014, but see also Geels, 2011). A more serious shortcoming, perhaps, is their evident debt to “the traditional, technology-focused application of the term ‘innovation”’ (MacCallum et al., 2009), which seems poorly-aligned with the emerging emphasis on human agency and social capital that the concept of SI seeks to emphasize.

The role of social capital is examined by Bauwens and Defourny (2017), in their study of renewable energy cooperatives in Belgium. They consider three different forms of social capital: social identification with the cooperative, generalized interpersonal trust and network structure, and conclude that while moving toward a mutual benefit model, focusing on meeting member's needs, e.g., by supplying green electricity, may allow community energy organizations to increase their size, impact and financial stability, social capital may become diluted as a result.

Becker et al. (2017) examine community energy through the lens of social entrepreneurship, in order to develop an integrated approach for analysis of small-scale and bottom-up energy initiatives using a tripartite framework oriented around “the purpose of the initiative, its form of organization and ownership, and its embeddedness into local community or wider social movements” (Becker et al., 2017). Hiteva and Sovacool (2017) examine SI in energy service companies (ESCOs) from the perspective of energy justice, defined as “as a global energy system that fairly disseminates both the benefits and costs of energy services” (Hiteva and Sovacool, 2017). They find that established firms who try to incorporate principles of energy justice into their business models may deliver these goals less successfully than companies, like the UK-based Robin Hood Energy, that have been created for that purpose.

A related term is “energy democracy” which originated in an important study of a range of European CE initiatives (Kunze and Becker, 2014). Energy democracy is attributed by these authors to the climate justice movement, and defined as ensuring access to energy for all, producing it without harm to the environment or climate, democratization of the means of energy production and rethinking our attitude to energy consumption. Szulecki (2018) notes that, seen as a policy goal or an ideal socio-technical arrangement, energy democracy is a “quasi-utopian idealization,” but suggests that key elements of the energy democracy ideal can be operationalized for policy purposes. The three elements he selects: democratic popular sovereignty, participatory governance, and civic ownership, are recurring themes in CE, and, as we discuss later on (see: Analysis and Discussion of Results from Survey and Literature Review), are also key to our own conceptualization of SI.

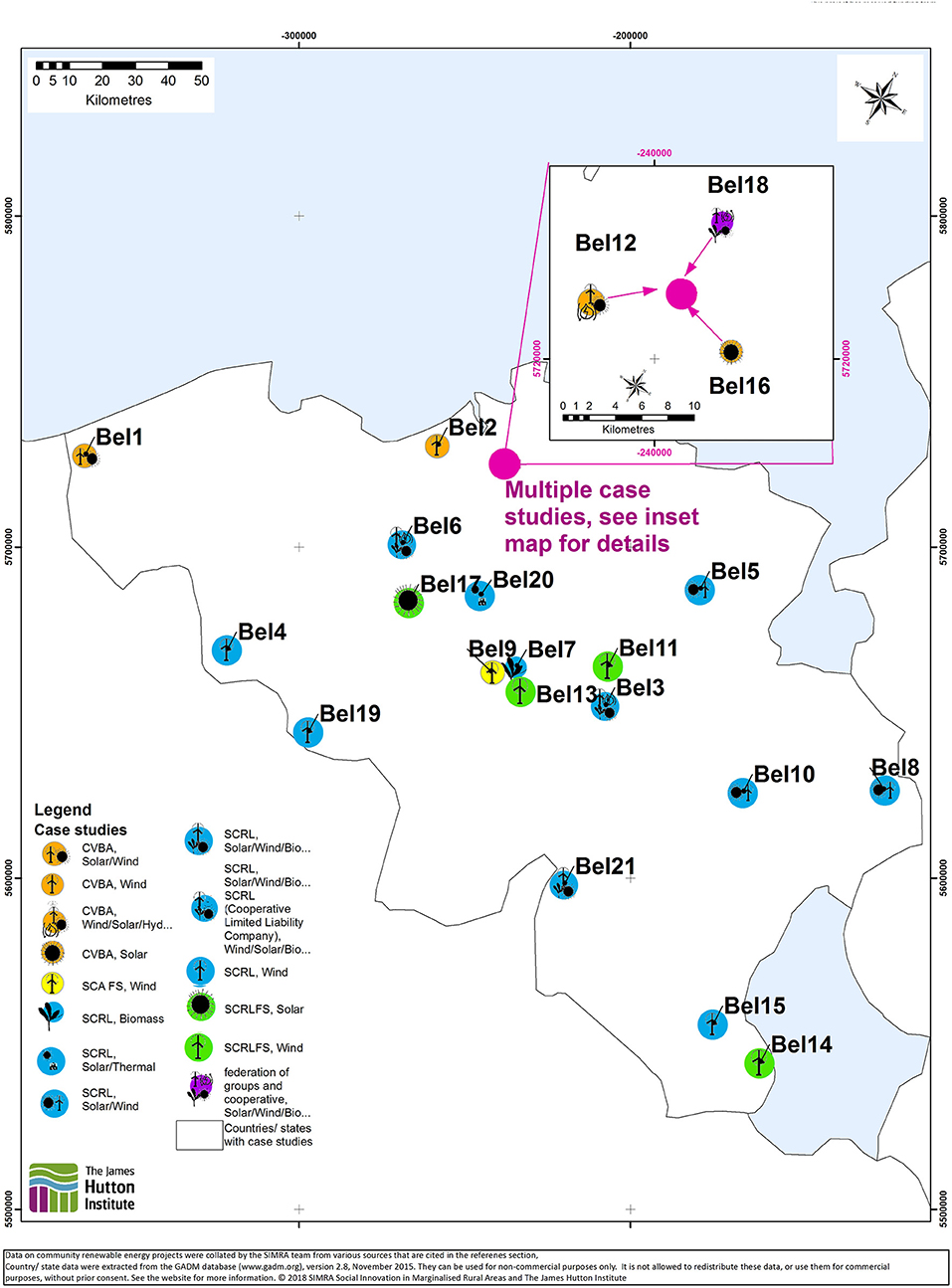

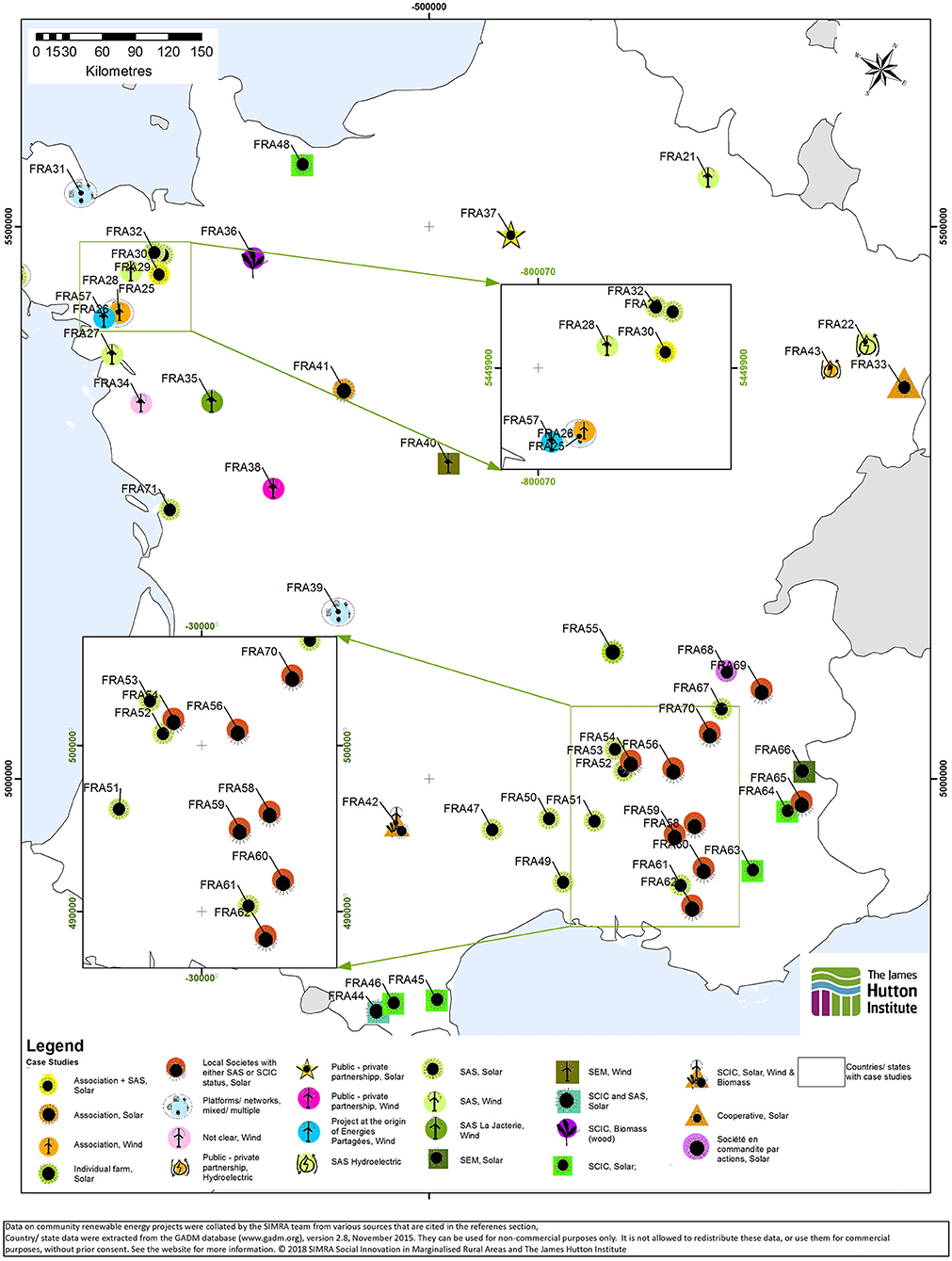

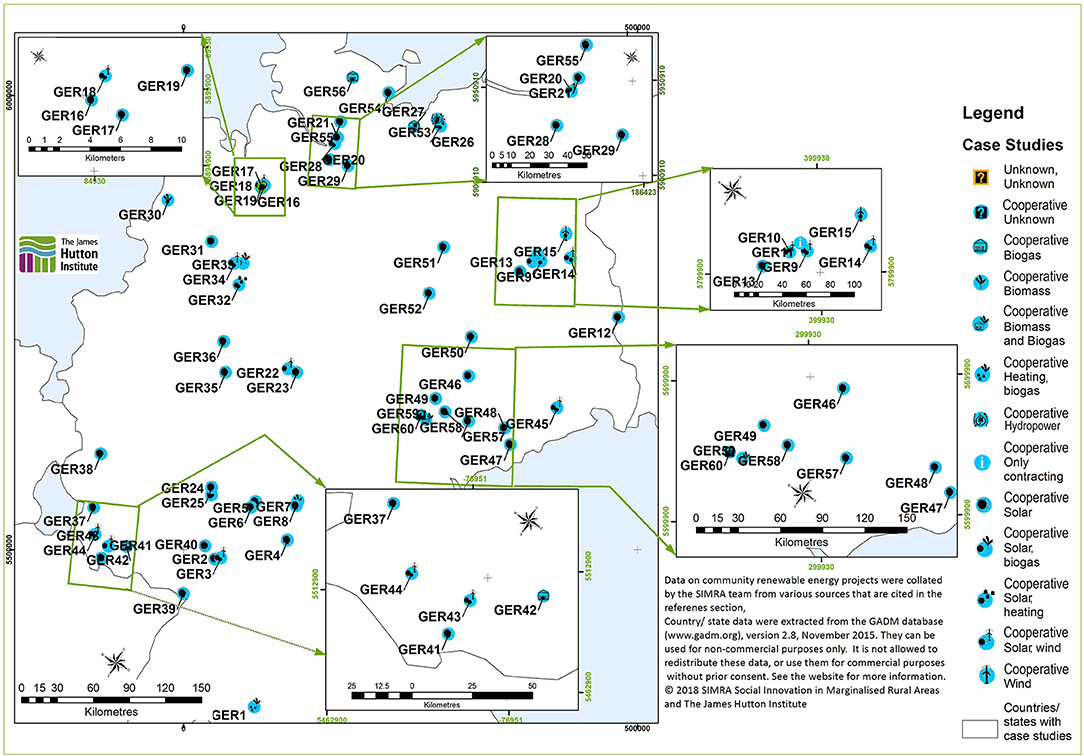

Search and Mapping Exercise of CE in 8 European Countries

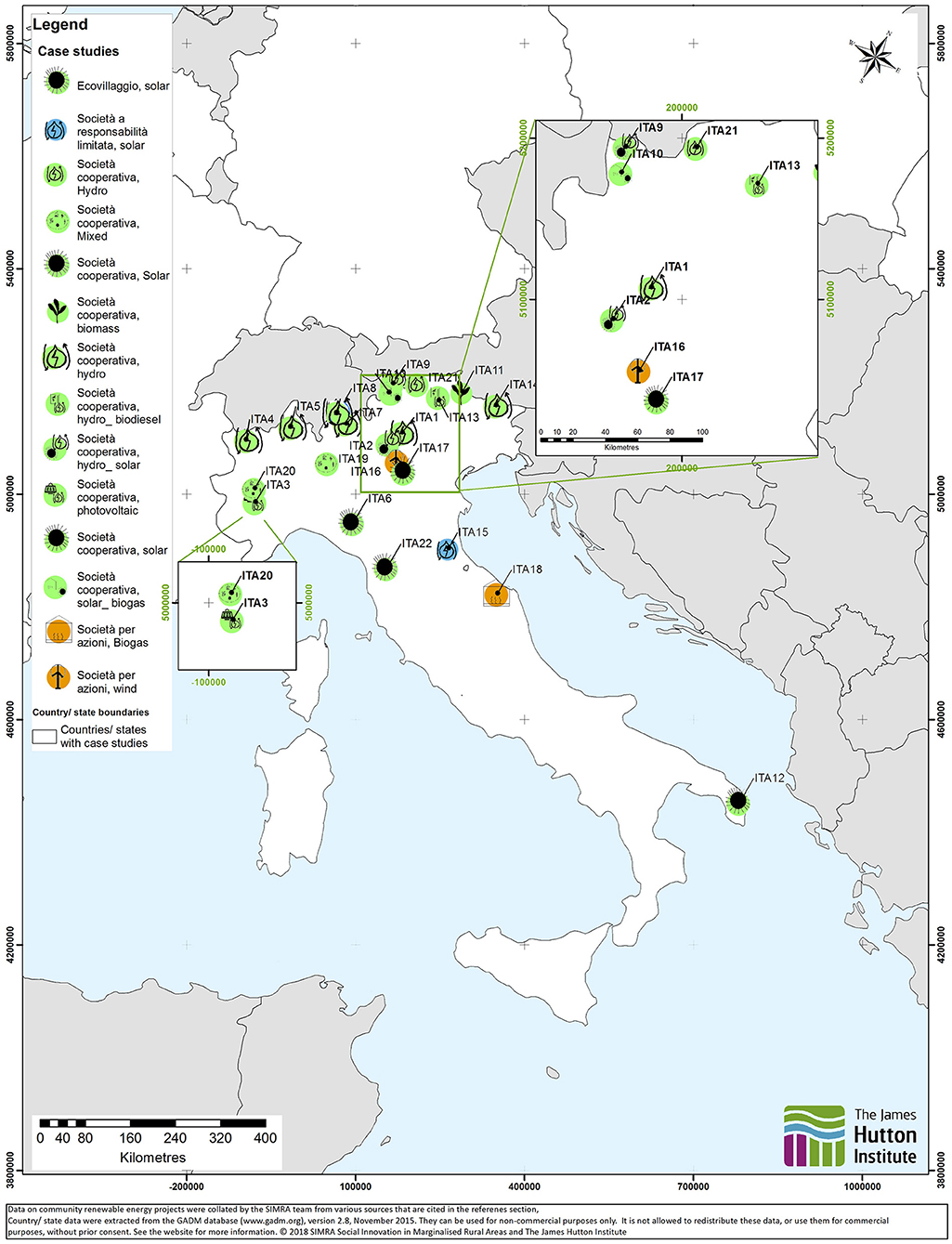

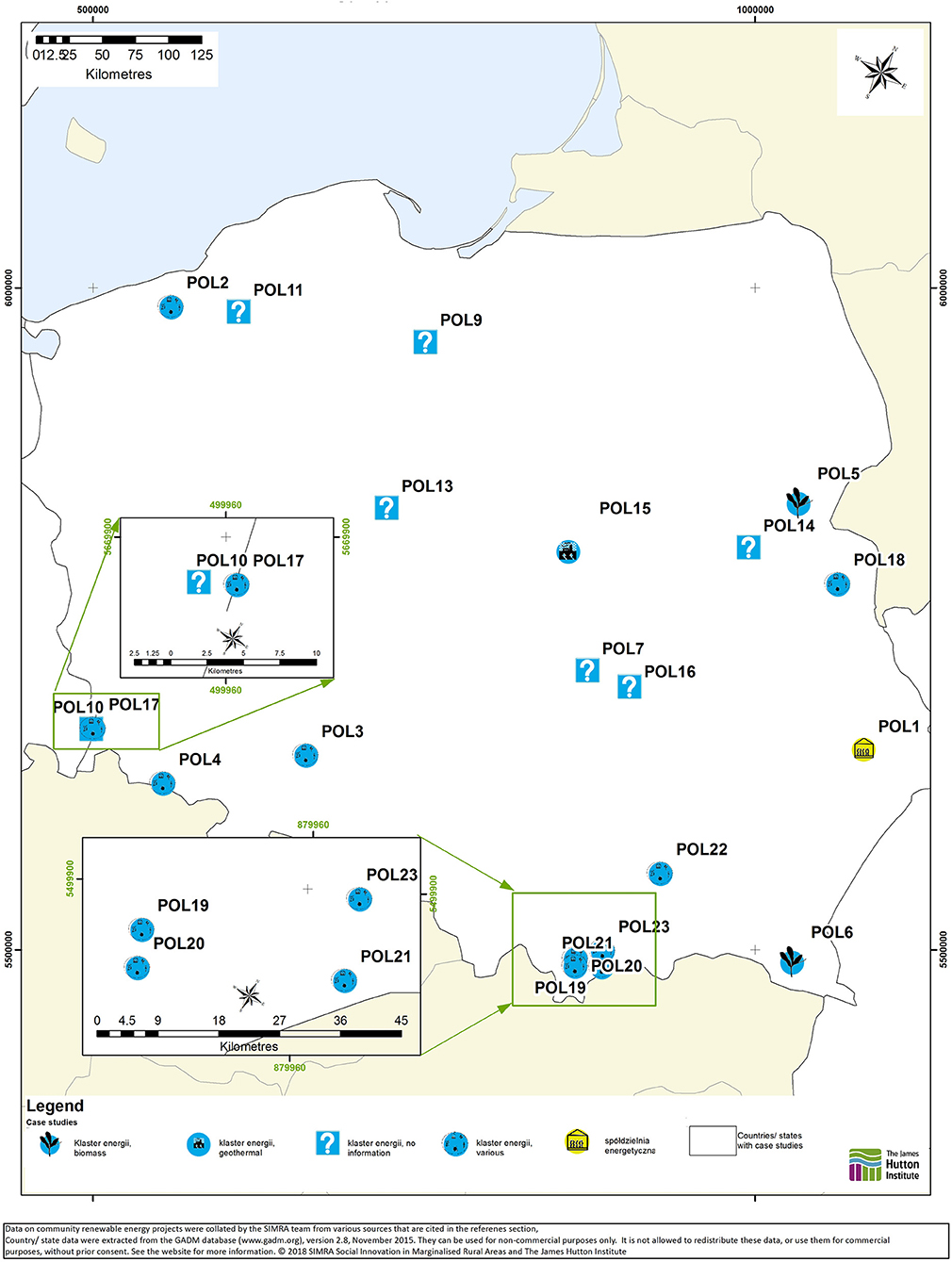

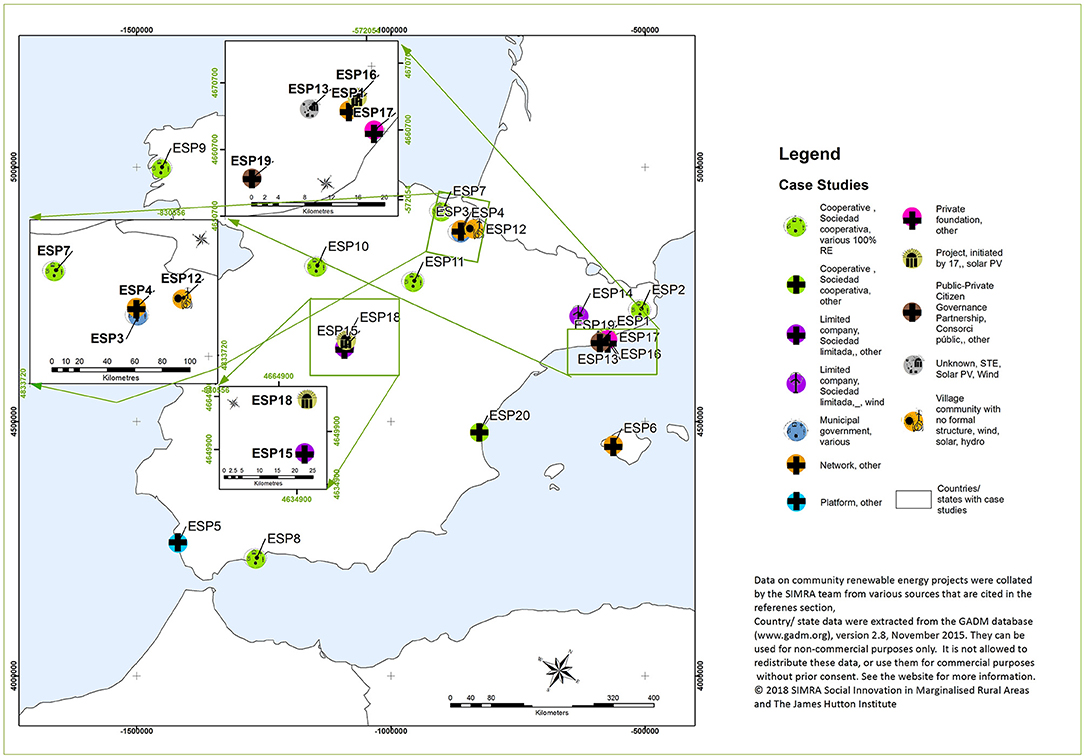

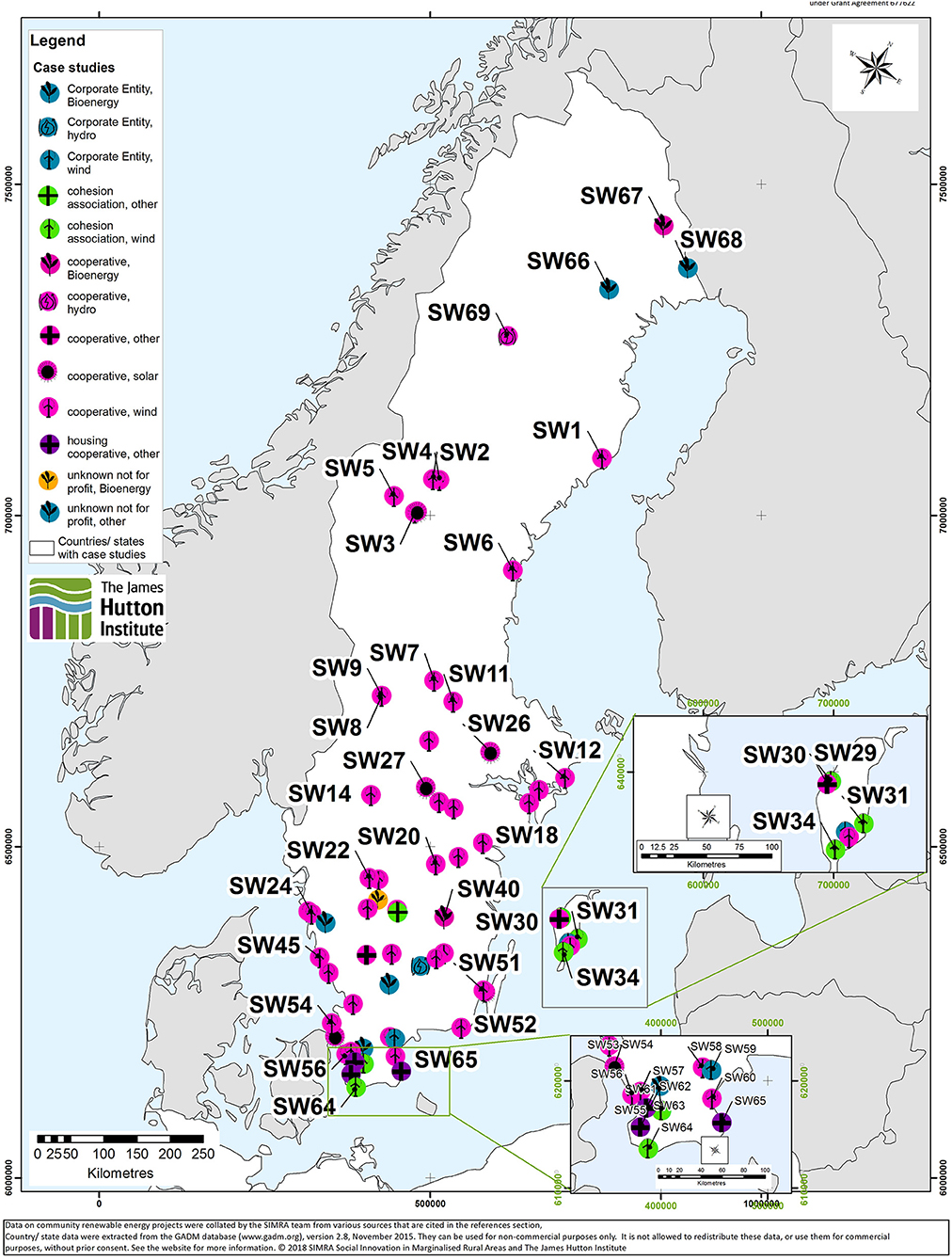

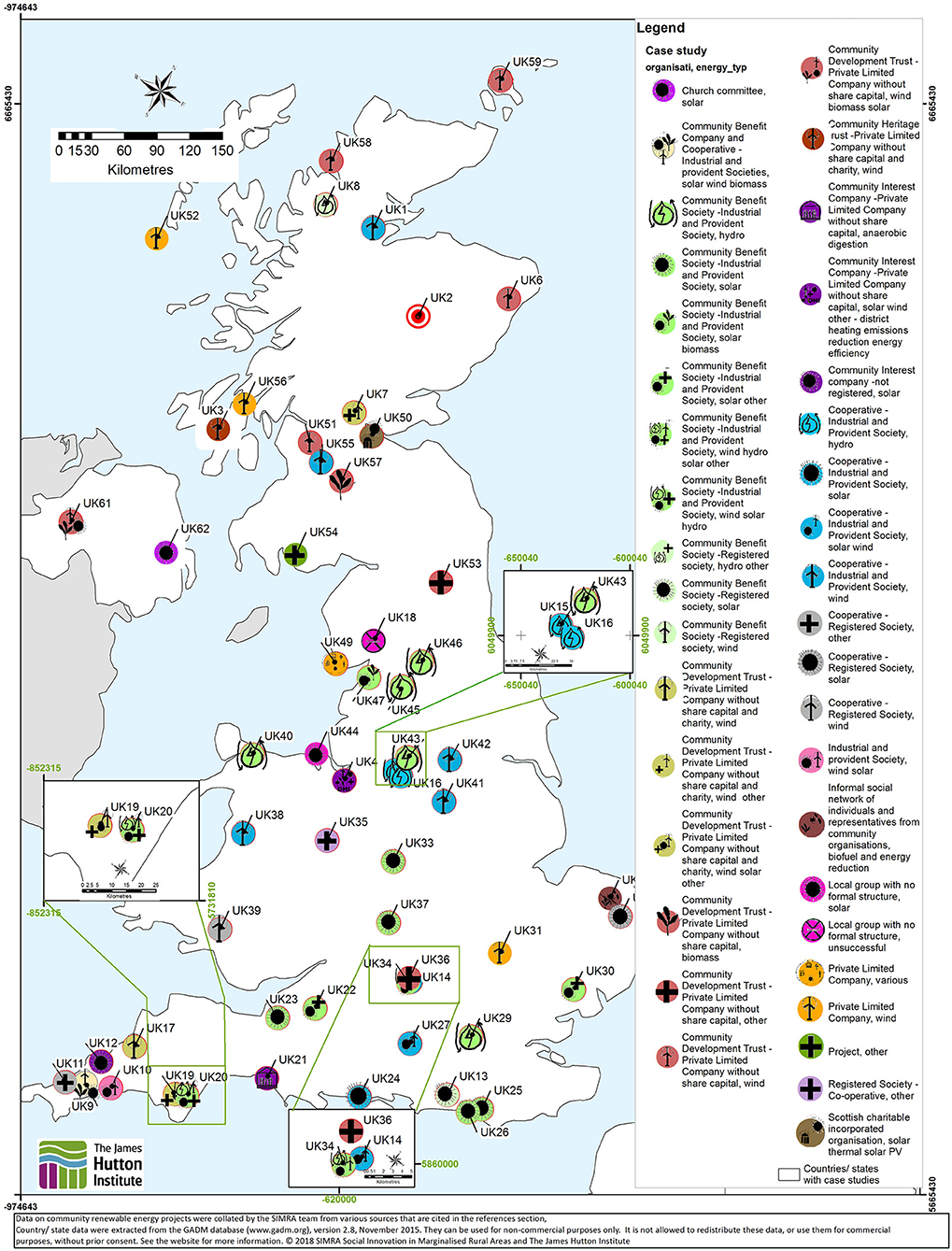

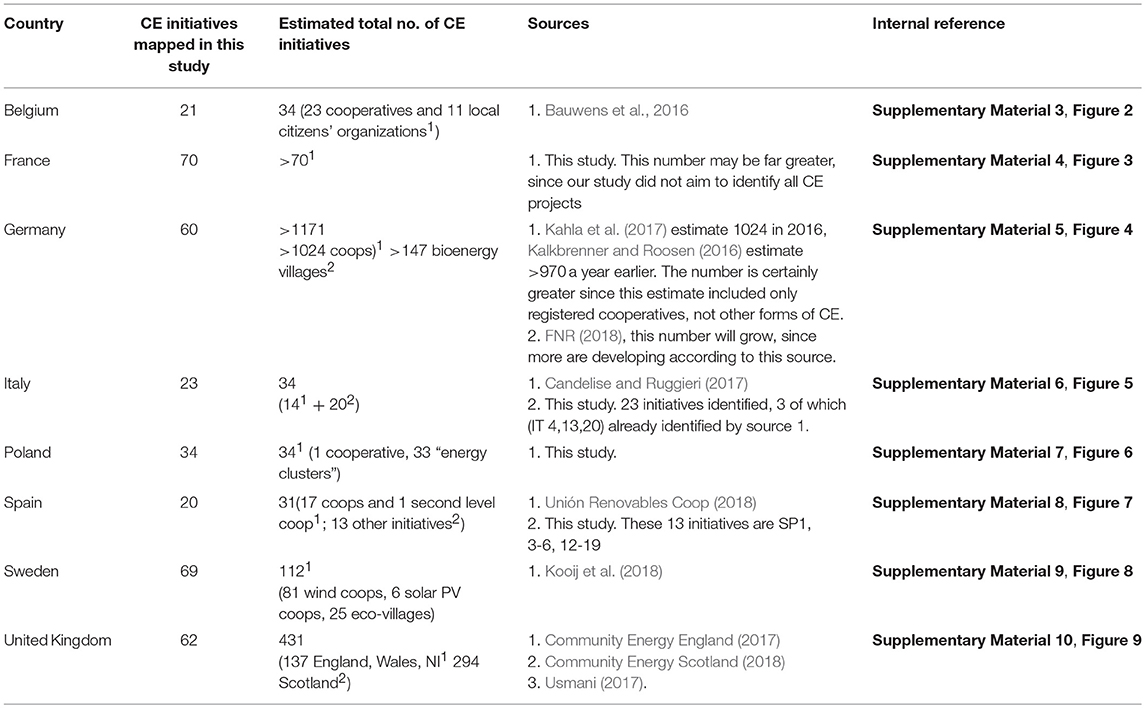

Figures 2–9 show CE initiatives for the 8 case study countries compiled from diverse sources. A list of key literature for each country is provided in Supplementary Material 1. A summary of the main CE developments in each case study country is given in Supplementary Material 2. Full lists of CE initiatives identified can be consulted in Supplementary Materials 3–10, these are referred to in the text below. Information was compiled on 2 key levels; CE type (wind, solar, biomass etc., or other – i.e., an organization dedicated to energy supply, rather than generation) and organization type (the legal name in the home language, as well as its approximate rendering in English). Estimated total numbers of CE initiatives for each case study country, and the sources from which these figures are derived, are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Numbers of CE initiatives mapped by this study, and estimated total numbers of CE initiatives from literature.

Energy Type

In terms of energy type, as would be expected, the distribution broadly reflects the geographical characteristics, for example, differing potential for wind and solar, of the countries themselves. In Sweden, wind energy dominates, with a small number of solar PV projects in the south; in the UK, most large solar installations are located in the south of the country, with wind and hydro dominating elsewhere (especially in Scotland, where wind conditions are generally good); and in Spain and Italy, solar PV installations are dominant nearly everywhere. The clearest exception to this general tendency is Germany's huge solar power capacity, reflected in CE just as in RE in Germany generally. Of the 973 renewable energy service cooperatives (REScoops) identified by Bauwens et al. (2016), only 82 were dedicated to wind energy, the remainder mostly being solar cooperatives (e.g., GE 8, 17, 48). This seems to be because of the higher returns from solar energy, together with the preference for the limited partnership model (GmbH & Co. KG) for community wind projects (Bauwens et al., 2016). In general, the chronological development of wind and solar schemes reflects the pattern of RE development as a whole, with community wind schemes emerging mostly in the 1990s (e.g., UK 48, SW 14), and solar cooperatives a decade later (Holstenkamp and Ulbrich, 2010; Oteman et al., 2014, note only 4 solar cooperatives in Germany in 2007, rising to over 200 by 2010, this pattern is reflected in the UK and Sweden). Spain is an interesting exception to this rule. While the country is quite typical in terms of chronological development of RE generally, with the wind power boom of the 1990s followed by a solar PV boom in the mid-late 2000s (Alonso et al., 2016), the first community wind turbine at Pujalt near Barcelona (SP 14) became operational only in summer 2018, long after the crowd-funded solar projects at Mercado del Carmel in 2007 (SP16) and Universidad Autónoma de Madrid in 2009 (SP 18). This is likely to be because the capital investment required for small rooftop solar arrays like SP16 and 18 is much smaller than for a wind turbine like SP14, and Spain still lacks a supportive policy environment to manage these risks (Hewitt et al., 2017).

In Italy, community hydro schemes dating back to the turn of the twentieth century are to be found in the northern regions of Trentino and South Tyrol (e.g., IT1; IT7), reflecting the historic importance of the Alps for hydroelectricity. Elsewhere, community hydro schemes are less common, and quite different in nature than these Italian customer-owned hydro electricity utilities (Mori, 2013). Anafon Hydro in Wales (UK 40) and BürgerEnergie Lübeck (GE 53) are good examples, there are others in France and Sweden (Energy Archipelago, 2018). In the UK at least, where many community hydro schemes are found, our searches identified 3 such schemes that failed to get past the planning stage (e.g., UK 18). The reasons behind this are unclear (though see Hielscher, 2012) and may warrant further investigation.

Bioenergy, which is widespread in Europe, is generally less well-represented in the CE literature, perhaps because schemes are often centrally controlled, either by a public body or a large energy company, or under individual ownership (e.g., on-farm), rather than community enterprises. In the UK, biomass CE initiatives are generally small-scale, e.g., for heating community centers and churches (e.g., UK 57). There are a small number of biogas schemes in France, e.g., Méthadoux, near La Rochelle (FR 51), which bring together local livestock farmers to produce energy through a limited liability company (SAS). In Italy, community bioenergy projects are not clearly in evidence, the biogas company So.ge.nu.s Spa (IT18) seems to be a consortium of municipalities and is not noticeably citizen-controlled. In Spain, the pioneering cooperative Somenergia (SP2) produces electricity for its members from an anaerobic digester at Torregrossa, Lleida. In both Poland and Belgium, government support schemes for green energy have favored large scale incumbent providers, who have adapted by burning biomass in coal-fired plants [Bauwens et al., 2016; International Energy Agency (IEA), 2017], rather than CE initiatives. In Sweden, despite major restructuring of the District Heating market, which is largely dependent on biomass (from 95% municipal owned in the late 1980s to 51% sole municipal ownership in 2014), there is little evidence of participative community involvement beyond a handful of cooperatives (Magnusson, 2016). However, as in the French case, there are some small limited companies set up by groups of farmers, like Farmarenergi i Eslöv AB (e.g., SW 55), which provides heating for local homes.

In Germany, however, community bioenergy plays a significant role in the form of “bioenergy villages” (e.g., GE 59). The number of such villages, which produce electricity and supply local heating needs by burning food and animal waste in combined heat and power plants, has increased enormously since the first was established at Jühnde, in Göttingen, in 2000 (Wüste and Schmuck, 2012). Today (September 2018), they are found all over Germany; the Agency for Renewable Resources (FNR) lists 147 bioenergy villages, and another 44 “on the way” (FNR, 2018). Though bionenergy villages are strongly promoted at regional government level, with, for example, the state of Baden-Wurttemberg offering to fund the development of 100 bioenergy villages by 2020 (Wüste and Schmuck, 2012), Boch und Polach et al. (2015) have suggested that social capital and trust among key stakeholders, as well a strong local initiator, are key factors in success or failure of initiatives.

Finally, there are a wide range of initiatives where energy type is denoted as “other”; these include initiatives dedicated to supply of energy or energy-related services rather than generation (e.g., SP 7,8) or to broader considerations like carbon-reduction, fuel poverty goals or “transitioning” society to more equitable and sustainable pathways (e.g., UK 4,5, SP 19).

Organizational Type

REScoops

In terms of organization type, Renewable Energy Cooperatives (REScoops) of various forms are by far the most common class of CE. These have broadly comparable legal forms in most countries, e.g., Ekonomiska förening (Sweden), Industrial and Provident Societies (UK) or Energiegenossenschaften (Germany). Most such cooperatives are old, though reorganizations of their legal structure in many countries since the 1980s, e.g., in Italy, Spain and the UK, have allowed elements of social enterprise to be introduced in response to a growing need for third sector involvement in multiple areas of activity (Borzaga and Defourny, 2001). The limited presence of REScoops in some countries, is often related to difficulties of the cooperative form, e.g., in Spain, cooperatives could not market electricity before 2010 (Romero-Rubio and de Andrés Díaz, 2015). In Germany, most of the large number of REScoops (>1,000, see Table 1) are nowadays dedicated to producing solar energy. This is because wind farm projects have mostly adopted the GmbH & Co. KG model, where voting rights depend on the proportion of capital invested, not on the traditional “one member, one vote” cooperative principle (Bauwens et al., 2016).

All of these cooperatives in their respective countries serve to allow their members to carry out economic activity through energy generation or supply. Some own energy infrastructures, or shares in them, e.g., hydropower plants, wind turbines or solar farms, others act only, or mainly, as resellers of energy from renewable sources. Some provide energy to members or local people directly (e.g., UK 59) but most sell electricity to the market and pay dividends to their members (e.g., SW7, UK13, GE29). In Spain, REScoops mostly act as resellers of energy to their members (SP14 is a notable exception), using energy source accreditation schemes to guarantee 100% renewable energy. However, Som Energia (SP2), the largest and oldest of the Spanish REScoops, does own some RE plants, and recently became the first developer to build a solar PV plant without any form of subsidy (Rodríguez Íñigo, 2015). In Italy, in addition to offering members returns on their investments, REScoops also may offer additional benefits, such as payments to citizens who provide assets like rooftops (e.g., Retenergie, IT 3), royalties or rents to the municipality, or discounts on energy bills (Candelise and Ruggieri, 2017).

In Poland, there is just one officially-registered energy cooperative (Nasza Energia, PO 1). However, this seems to be an initiative arising from the business sector, rather than a bona fide citizens' movement (Rabiega, 2018; telephone interview). One possible reason for the lack of energy cooperatives in Poland may be that the cooperative model is negatively associated in the minds of citizens with the state socialism promoted by the communist regimes before 1990 (Beckmann et al., 2015).

Community Development Trusts

In the UK, most notably, but not exclusively, in Scotland, development trusts or community benefit companies are prominent. Community Development Trusts (CDTs) and Community Interest Companies (CICs) (e.g., UK 6,7,17, 36) are typically Private Limited Companies without share capital, whereas Community Benefit Societies (CBCs) are usually Registered Societies (the UK legal form of a cooperative). Both of these are managed by a board of community representatives, returning income to the community as a whole, rather than just investors.

These UK organizational forms have received recent attention from Harnmeijer et al. (2018), who compare and contrast organizational structures of CE initiatives in different parts of the UK (England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland). They note that while CE initiatives are often thought of as egalitarian by nature, some organizational structures are more egalitarian than others. Some cooperatives may be less egalitarian than CDTs, in the sense that the cooperative structure relies on delivering return to individual investors rather than investing in projects for the whole community, like CDTs and CICs (Harnmeijer et al., 2018). This distinction is comparable to the “public versus mutual benefit” dichotomy identified by Bauwens and Defourny (2017) in their analysis of energy cooperatives in Belgium.

Local Government Projects With Citizen Participation

In France, where energy has traditionally been highly centralized, the Pluriannual energy program (PEP) adopted in 2016 (Ministère de la Transition écologique et solidaire, 2016) has sought to increase citizen participation in energy by prioritizing installations funded through citizen share offers. These “crowdfunded” developments are normally initiated by municipalities, who initially own the capital and then open the project to local citizen participation (Christen and Hamman, 2015). This was the case, for example, of a wind farm comprising 10 turbines installed across 6 communes (municipalities) in the department of Vosges et Bas-Rhin). In this 2008 pilot project managed by the specialist company Énergie Partagée, who help with capital financing and manage risk, the municipality first owned 40% of the shares and then opened up the remaining 60% to citizens (Christen and Hamman, 2015, 127).

Thus, in France, and also in Italy, local government, which is highly autonomous, compared with the UK, is a key driver of CE projects. In France, as we have seen, municipalities are key project initiators, while in Italy they may provide supportive local policy frameworks or assets like the rooftops of public buildings (Candelise and Ruggieri, 2017). In Spain, the tendency is less clear, probably because community energy generation initiatives are less common. However, Noáin municipality, near Pamplona (SP 3, is one such example, and Viladecans (Vilawatt, SP 19), in Barcelona, is another. Both of these initiatives are strongly focused around energy efficiency measures, in the case of Noáin, the primary motivation cited is climate change, while the Vilawatt initiative in Viladecans looks to reduce citizen's energy bills and end dependence on large energy companies (Bessete, 2018). The Cadiz energy transition roundtable (SP 5) is clearly promoted by the town council.

In this context, the newly emerging Polish “energy clusters” are relevant (PO 2-34). One of the main reasons hampering the development of the CE in Poland has been the lack of regulations determining the legal form of such initiatives. However, while the legal form of an (energy) cooperative does formally exist in Poland, the government has introduced and intensively promoted a different concept, namely the energy clusters (klastry energii). Energy clusters are defined as a contract between various actors (individuals, legal persons, business entities, research entities, and local municipalities), for the purpose of energy generation, balancing, trade or distribution. However, legislation also specifies that the energy used by clusters is not necessarily limited to renewables (Sejm, 2015). In order to hold the formal title of “energy cluster” such initiatives must obtain government approval (so far 33 such initiatives have done so). Having the officially recognized label increases the chances of receiving external funding, e.g., from the National Fund for Environmental Protection and Water Management. Most energy clusters seem to have been established either by the local authorities or the business sector, with a small rate of citizens' participation. However, despite these clear limitations and early stage of their development, energy clusters can be seen as a positive development within Poland's highly centralized, coal-based energy tradition, representing a cautious move toward a low carbon-economy and energy decentralization.

Public-Private Partnerships

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) are a key feature of CE in many countries. In France, companies like Énergie Partagée and Enercoop, which emerged during the liberalization of the energy market after the year 2000, help finance municipal-driven projects with citizen share offers. This serves to mitigate the financial risk to the municipalities that initiate the project. However, while PPPs are often seen as an ideal way to combine market efficiencies with public interest, they are not necessarily always inclusive, and public-participation “needs to be designed in, not assumed-in” (Lowndes and Sullivan, 2004). For this reason, the Vilawatt project (SP19) has established a public-private-citizen partnership (PPCP) to ensure citizen representation alongside private companies and public entities.

Private Companies

Often, while energy installations may be owned by cooperatives, electricity generation is carried out by a private company, either a separate commercial entity like Dala Vind AB (SW 7) or a wholly-owned trading arm of the cooperative or trust, like Makassar, which runs the Torregrassa biogas plant for Somenergia (SP2), or the Udny Wind Turbine Company (UK 6). Often, where electricity generation is the sole or main objective of the scheme, such as in farmers' biogas collectives (e.g., FR51 and SW55), a private limited company is the preferred option. While literature often focusses on the supposed altruistic nature of CE schemes, and thus may exclude “for profit” organizations, this risks missing the point of many such projects—to make money for local people. In fact, one of the prime motivators of such schemes is the realization by local actors that RE subsidy mechanisms like Feed-in-Tariffs (FiTs) can be accessed by the communities themselves through the same structures (i.e., companies) used by larger operators. However, small companies may often find themselves at a considerable disadvantage when compared to larger, established energy companies. In Germany, for example, while legislation (EEG, 2017) aims to achieve a high diversity of actors in the energy transition, in practice, significant barriers remain for smaller organizations. These barriers relate to institutional and policy designs conceived for large energy suppliers, like taxes and grid access costs that are excessive for smaller organizations, and reporting requirements designed for the big energy industry (Oppen et al., 2017).

Other Grassroots Initiatives

Also very widespread, but less easily classifiable, is a broad range of local initiatives, prominently the eco-villages of Sweden (e.g., SW 63; Magnusson, 2018), occupied villages like Lakabe, in the Spanish Pyrenees (SP 12), projects allied to the transition towns movement (e.g., UK 20), and the citizens' energy “platforms” like the (unsuccessful) Berlin Energy Round Table (Becker et al., 2017) and other initiatives like those that have recently (after 2012) begun to emerge in Spain (SP 1, 5, 6). The organizational form is less relevant in these cases, being largely a matter of convenience, if it exists at all. These grassroots movements in CE are mainly oriented around two key themes, (1) sustainability and environmental issues, often from an anti-consumerist perspective; (2) energy democracy and fuel poverty. Though in practice these social movements are often allied, they respond to different crises, an ecological crisis in the former case, provoked by climate change, and societal failure to act, and a socio-political crisis in the latter, arising from the failure of governments and markets to meet citizens' energy needs in an equitable way (see Discussion).

Analysis and Discussion of Results From Survey and Literature Review

Social Innovation in European Community Energy

CE is discussed in the light of the four key criteria we identified earlier for evaluation of the SI concept as follows:

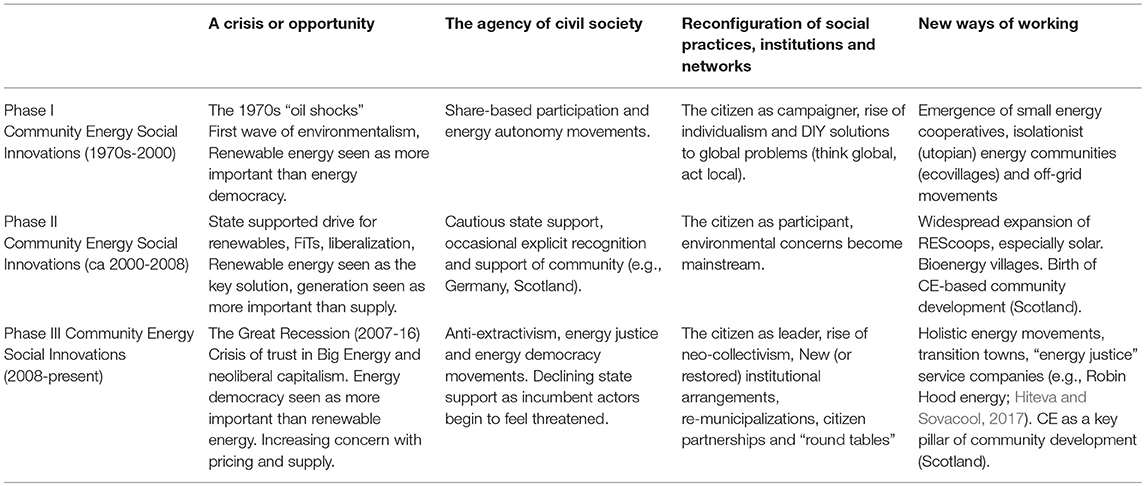

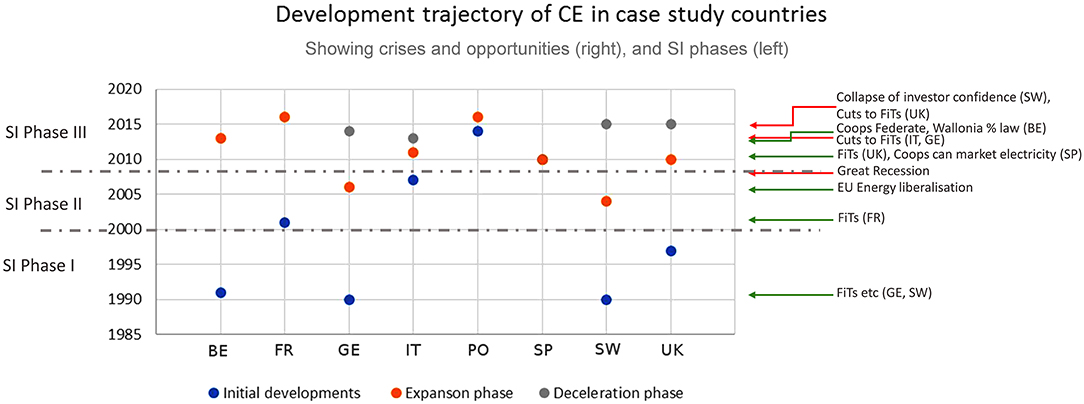

Crises and Opportunities

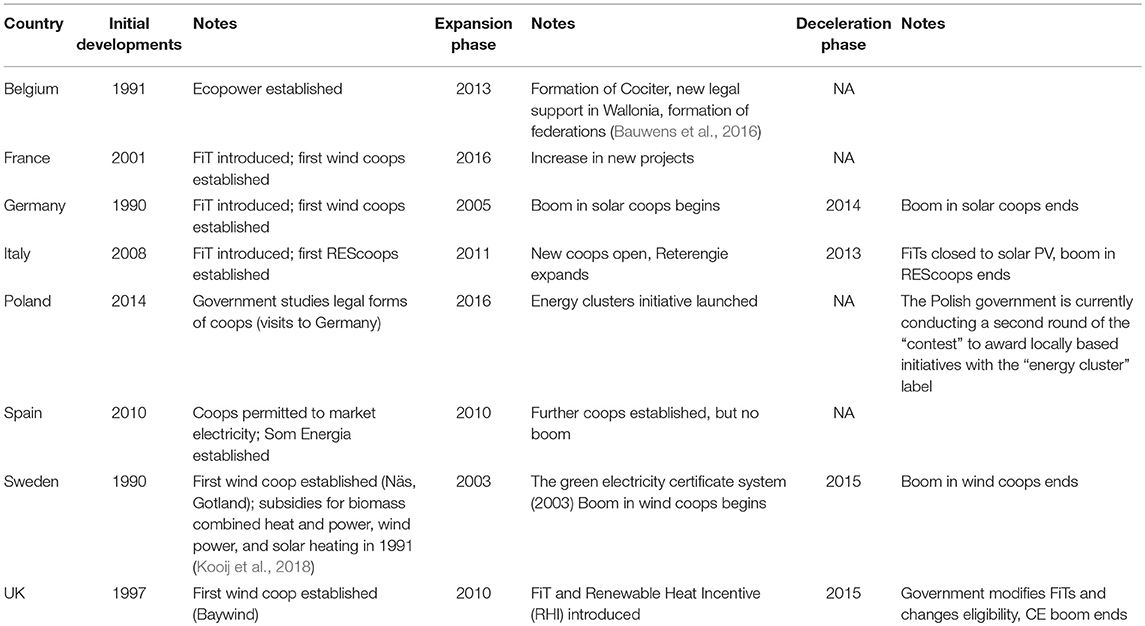

To be able to recognize an innovation, we need an historical timepoint that serves as a clear benchmark for change from the earlier systems or procedures of that time to the later systems or procedures that we may characterize as innovative. The origins of CE have been attributed by various authors to the social and environmental and movements emerging in Europe in the 1960s and the “oil shocks” of the early 1970s (e.g., Cowtan, 2017; Kooij et al., 2018). However, while this explains the development of renewable energy generally and the growing awareness of citizens around energy issues, it does not explain the reason for the sudden increase in CE initiatives after 1990, or the subsequent, more recent waves of development up to the present day. These are summarized in Table 2 and Figure 10.

Figure 10. Development trajectory of CE in case study countries, showing crises and opportunities (Right) and SI phases (Left).

Firstly, the timeline (Table 2) clearly shows that CE, at least in its mainstream sense of REScoops providing generation and supply services, is clearly linked to the availability of appropriate organizational forms and policy instruments. In Germany and Sweden, for example, REScoops were not so much alternative vehicles for communities to democratize energy, but pioneering initiatives that drove the development of mainstream wind power in the early 1990s (Enzensberger et al., 2003; Wizelius, 2018). In these countries, when wind power began to take on importance, developers reached for models to permit the financing of these risky enterprises, and cooperatives fitted the bill at that time. This was not the case elsewhere, where cooperative structures did not (or could not) occupy this crucial niche. In Spain and Italy, for example, massive expansion of wind power took place from the early 1990s (Bilgili et al., 2011; Ramírez et al., 2018), yet REScoops were not involved in this process at all. Instead, this niche was occupied by companies like EHN (later Acciona) and IVPC (International Energy Agency (IEA), 2001). In the UK, the first commercial wind farm was developed in 1991, yet no CE wind power scheme emerged until 1997 (Cowtan, 2017).

The key role of incentives as enablers for CE schemes is also clear from Table 2. In Sweden, France, Italy and Germany, CE projects did not emerge in significant numbers until public subsidies like FiTs became available. After a slow start, CE also took off in the UK after 2010 exactly coinciding with the introduction of FiT and RHI (Renewable Heat Incentive) subsidy schemes. The reverse is also true. In in Germany, gradual reduction of FiTs for solar PV installations in 2012 (Baur and Uriona, 2018) led to a reduction in the growth of new PV cooperatives, likewise in Italy, where growth slowed after PV schemes became ineligible for the FiT scheme (Candelise and Ruggieri, 2017). In the UK, government reductions in FiT payments and changes to eligibility criteria in 2014 led to a noticeable reduction in CE initiatives since then, despite the otherwise strong institutional support framework (Cowtan, 2017).

A number of other clear factors emerge as highly important. If FiTs paved the way for the first wave of CE initiatives in northern Europe, the EU directive on liberalization of the electricity market (applied to all consumers by 2004) seems to have been a key factor in allowing CE initiatives to enter the market (Kooij et al., 2018). In Scotland which has seen much stronger growth in CE than elsewhere in the UK (Harnmeijer et al., 2018), a community development body (Highlands and Islands Community Energy Company; HICEC, later Community Energy Scotland) established in 2004, was able to take full advantage of the rapidly changing policy scenario by making the crucial link between community development and renewable energy. The Community Development Trust model (see section Community Development Trusts, above) was thus an opportunistic phenomenon arising out of a particular set of circumstances that were probably unique to Scotland at that time. However, uptake of renewables by the private sector had been generally disappointing UK-wide, thus the failure of the private developer-led model also provided an opportunity (that might not otherwise have been available) to try something new (Van der Horst, 2008).

The local social context in different European countries, or between regions within individual countries, is also key. Without social capital (following Bauwens and Defourny, 2017, see above), or a culture of local participation, CE cannot easily emerge. The distrust felt by Polish citizens toward cooperative models of social organization is clearly a major factor in the absence of REScoops in Poland, and probably also explains the low level of development in the former GDR areas of Germany (Bauwens et al., 2016). Perhaps a CE model emphasizing local enterprise rather than cooperative values might be more successful in these areas.

More recently, the growth of CE initiatives in many countries has been strongly influenced by the global financial crisis and subsequent recession that began in 2007 and continue to have grave consequences across Europe. This “Great Recession,” known in many European countries simply as “the crisis,” arguably has had much more direct, consequential and long-lasting impact on the individual European citizen than the 1970s oil shocks. Nevertheless, the two events are clearly related, and in energy terms, the earlier event is a clear precursor to the later. The oil shocks showed clearly the power of the global energy giants to the ordinary citizen, perhaps for the first time (Mitchell, 2011). In a similar way, the sharp upsurge in interest shown by citizens in issues relating to control and supply of energy, especially as a means to decrease their household expenditure on energy, is certainly related to this more recent crisis. In Southern Europe, where the effects of the crisis were more strongly felt than in the more diversified economies of the North (e.g., Germany, France, UK), this can be clearly demonstrated. In Spain, the crisis has clearly been as a key factor in driving the emergence of the supply REScoops like Som Energia (SP2) (Capellán-Pérez et al., 2018; Heras-Saizarbitoria et al., 2018). To give another example, the Cadiz energy transition roundtable (SP 5), can trace a direct lineage from the anti-austerity social movements of 15th May 2011 (15M), to the formation of the anti-austerity party Podemos in 2014 to the electoral success of that party and associated grassroots movements in the local government elections of 2015, in which they took control of the city. The ongoing movement for energy transition in Spain is directly emergent from grassroots activism around austerity in the context of the Great Recession.

In summary then, European CE is an artifact of a range of different crises and opportunities, beginning with the social and environmental movements of the 1960s and 70s and the “oil shocks.” These can be broadly structured around three main phases of SI (Table 3). In Phase I, social and technological experiments laid the groundwork for the mainstream development of renewables in countries like Germany and Sweden, where, along with Denmark, the earliest of the energy cooperatives were formed. The process was facilitated by a range of policy instruments like FiTs and market liberalization which CE was able to take advantage of. Mainstream development of CE thus followed in the mid-2000s (Phase II), but it was not until the economic crisis in 2007–8 that social conditions were ripe for emergence of grassroots initiatives in Southern Europe to challenge the dominance of the big energy companies (Phase III). Neither France nor the UK were as severely affected by the crisis as Italy and Spain. Nevertheless, it is probable that this has led to a gradual erosion of acceptance of large developer-led schemes in the context of generally rising energy prices, which has facilitated the more recent emergence of CE schemes in these countries also. In the UK, especially in Scotland, CE is seen as a key facilitator of community development.

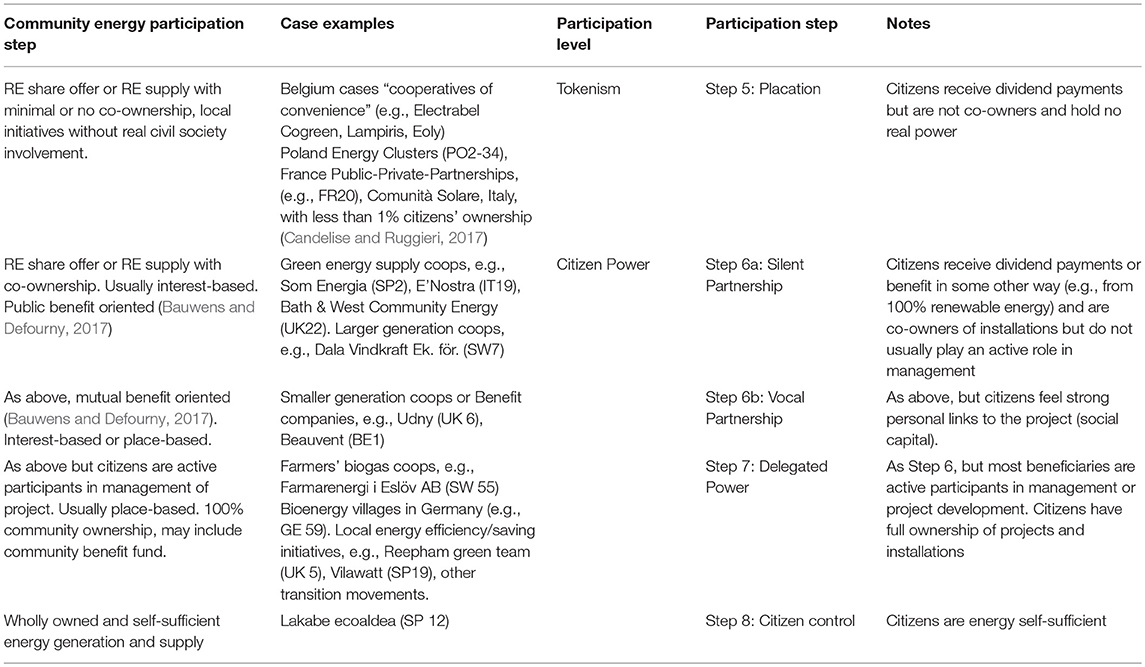

The Agency of Civil Society

Analysis of the extent to which CE initiatives are driven by civil society, as opposed to governments or private entities is a useful determinant of SI in this domain, since energy systems are traditionally centralized and non-participative. However, despite the large number of potentially applicable frameworks and methods, of which Arnstein's (1969) “ladder of participation” is perhaps the best known, it can be difficult to effectively evaluate the degree of civil society participation in projects. On one hand this is because local-scale governance structures (e.g., Spanish municipios or French communes) may sometimes represent civil society at least as successfully as parallel “unofficial” citizens' collectives. On the other hand, the ordinary electoral process may return control of the town hall to citizens' collectives, as happened most notably in Spain in 2015, as in the previously cited example of the city of Cadiz (SP 5). The problem is also compounded because many successful initiatives, as we have seen, combine public, private and citizens' groups (so called third sector). Despite these difficulties, some attempt to estimate the degree of civil society involvement in decision-making (participation) is worthwhile. In Table 4, we apply a modified form of Arnstein's (1969) ladder to European CE initiatives, highlighting some examples from our study.

The first point to note here, is that, by applying Arnstein's framework, the great majority of CE initiatives identified in our study do clearly involve some degree of citizen power. The exceptions to this rule are those “cooperatives of convenience” identified in Belgium, which are effectively subsidiaries of large energy companies and offer citizens shares, but not co-ownership of the project, and the various public-private-partnership schemes where citizens are effectively silent investors or are represented only by their local politicians, e.g., many of the French “Énergie Partagée” schemes and (at present) the Polish energy clusters. These clearly belong at the level of tokenism.

The second point to observe is that beyond this tokenistic step, a number of CE initiatives progress no further than Step 6, Partnership, where citizens benefit, but have no real power over energy generation or supply. These include both the supply REScoops, who tend to focus mostly on providing renewable electricity to their members (a public benefit model, e.g., IT20, BE12, SP2) as well as those that place more emphasis on generating return on investments to their members, like the wind cooperatives in Sweden and solar cooperatives in Germany (a mutual benefit model e.g., BE1, SW46, GE29). Bauwens and Defourny (2017) have suggested that social capital, defined as social identification with the cooperative, generalized interpersonal trust, and network structure, may be weaker in the former cooperative type than in the latter, and we have thus separated step 6 into two parts to account for this important distinction. Clearly, there is a great deal of overlap here, as social capital seems to be dependent on size, thus large Swedish wind cooperatives like Dala Vindkraft (SW7) are placed on Step 6a, and small-scale initiatives like Udny (UK 6) on Step 6b. Clearly, in the latter case, the place-based nature of the Udny scheme, which benefits all locals independent of their investment in the projects, is likely to increase social capital under the definition given by Bauwens and Defourny (2017).

In step 7, the place-based nature of the initiatives becomes paramount, and their size is generally small and local. In these examples, the emphasis is shifted entirely to community benefit, since financial benefit accruing to investors is non-inclusive in the sense that only wealthier (and often-better educated) community members can purchase shares. This step includes wholly owned and self-managed private enterprises, where everyone is a director and everyone makes the tea, as well as altruistic not-for-profit projects based around strong networks of (often unpaid) local participants. Logically, the high level of control that these initiatives have over their energy systems implies that most beneficiaries are actively involved in day-to-day running of the project. Effectively, being in control means doing a lot of it yourself.

In Step 8, this tendency is taken to its extreme, and here we find those unusual examples of off-grid communities, where, usually because of remoteness or inaccessibility, communities must build, and operate their energy systems without outside assistance. The motivations for this may be either deliberate choice, like the inhabitants of Lakabe, in the Spanish Pyrenees (SP 12), who occupied and rebuilt an abandoned village in pursuit of a way of life more closely connected with nature and self-sufficiency, or mostly by necessity, as on the island of Eigg, Scotland (Green Eigg, 2018). Both of these communities are entirely self-sufficient in terms of energy, but remain connected to the wider economy. The enormous challenges that such projects pose mean that these cases are likely to remain in a minority.

Reconfiguration of Social Practices, Institutions, and Networks

Firstly, this key aspect of SI implies that a recognizable change that emerges without such a reconfiguration is not a social innovation. The recognizable change that is being proposed by governments and large energy companies to meet the goals of the Paris Agreement is the large-scale deployment of renewable energy systems under centralized business models and market conditions that favor energy incumbents. This is a technological, not a social, innovation. These proposals go some way toward appeasing stakeholders whose predominant concern is the decarbonization of energy systems, even if progress on this narrowly defined goal is much too slow (Figure 1). However, in no case are any mainstream energy commentators proposing a transition from large scale energy production to small scale local grid and energy independent communities, mainly because of the enormous difficulty in achieving buy-in from powerful incumbents.

It is also clear from our study that institutional form, on its own, is not a useful criterion for determining what is, and what is not, a social innovation in CE. A farmers' bioenergy consortium (e.g., FR 51, SW 55), may involve more collaboration at the local scale than a community share offer from a wind farm. Yet the farmers' group is likely to be a private company, while the wind farm may be a wholly owned cooperative. Both, in our view, fit within the broad definitions of “community energy,” yet this designation tells us nothing about the nature of the initiative. Yet when we apply the criterion of “reconfiguration of social practices, institutions and networks,” we are on firmer ground. Though the initial reconfiguration of social practices that a wind farm community share offer entailed was certainly a valid social innovation in its day (see e.g., Maruyama et al., 2007), there has been no reconfiguration of a recognizable kind in most of our case study countries since the initiative became embedded practice in that country. In 2018, wind cooperatives are a successful and widespread institutional form in many countries, e.g., Sweden, Germany and the UK. For this reason they are no longer social innovations in these countries. However, context is essential. In Spain, where systematic barriers exist that must be overcome by complex negotiations between actors outside of their “comfort zone,” a community wind turbine (SP14, Viure de l'aire, 2018) is certainly a recognizable social innovation.

New Ways of Working

Conversely, with respect to the previous point, a reconfiguration of social practices, institutions, and networks should result in significant new ways of working to be identified as a social innovation. The key point here is that it is not difficult to identify apparently significant reconfigurations of social practices, institutions and networks in relation to energy that don't, in the end, lead to transformative change. For example, Magnusson (2016) found that the dramatic changes of ownership in the DH market in Sweden between the late 1980s and 2014 had, in the end, no real impact on consumers, who remained entirely at the margins of this transformation. The lesson from this example is to question whether the REScoops, that have proliferated to such an extent across Europe have really been transformative in terms of their stated goals, that is, greater citizen participation in energy and a transition to a low-carbon energy future. This is not an easy question to answer, and more detailed analysis of cases would be needed to give a clear response. As Lowndes and Sullivan (2004) have noted for the case of PPPs, greater participation of civil society needs to be demonstrated, not assumed.

Future Pathways: CE as a Road to Energy Democracy?

Our study suggests that a complete democratization of energy, such that all energy generation and supply is controlled and owned by citizens' groups is not likely to take place in the near future. However, CE is very widespread across Europe and deeply embedded, and there are some reasons to be optimistic about its future as well as some reasons to be less optimistic. Development models based on external ownership and limited local benefit have been increasingly challenged in many countries. Energy generation and supply across Europe is still dominated by just a handful of multinational companies (Darmani et al., 2016; Corscadden, 2018), and this is widely recognized as a serious problem for both energy affordability and the transition to cleaner energy systems (e.g., Barquin et al., 2006; Boroumand, 2015; Kungl, 2015; Ciarreta et al., 2016; Magnusson, 2016).

While national governments may be unable or unwilling to contemplate direct intervention, regional and local scale administrations face no such difficulty, and in Germany, for example, there has been a concerted drive to bring energy generation and supply back under local public control through “re-municipalization” (Wagner and Berlo, 2017). Recent years have seen a growing Europe-wide trend in favor of bringing services, including energy, back into municipal control after decades of outsourcing and privatization (Hall, 2012; Cumbers, 2016). In this context, CE has an important role to play in diversifying the energy market and more fairly distributing revenue from energy generation and supply. While mutual benefit-oriented REScoops like those in Sweden and Germany offer significant financial returns to investor-members, the case of the UK, particularly in Scotland, shows how energy projects can be used to fund community development directly. The difference between developer-led and community-led schemes in terms of direct financial benefit to communities is very notable—the 800 KW community wind turbine at Udny, Aberdeenshire (UK 6) returns the same benefit to the local community as Vattenfall's recently completed 93.2 MW offshore array at Aberdeen Bay–ca £150,000 in both cases (Local Energy Scotland, 2018; Vattenfall, 2018). The continued unpopularity of these kinds of large developments, together with the mounting evidence that public acceptance is likely to be greater where benefits accrue to the community as a whole (Rogers et al., 2008; Warren and McFadyen, 2010), means that it is not altogether utopian to imagine that very large projects like Aberdeen Bay might one day be partly citizen-owned. Indeed, this seems to be the direction of travel in Scotland at present with Scottish Government advice recommending community shareholdings, although not being entirely explicit as to sources of finance to underpin such community shareholding. At the same time, CE schemes are gaining in importance as energy suppliers, through RE supply cooperatives like Som Energia (SP2) and Ecopower (BE12). At present, one important limitation for CE projects is the need to negotiate with Distribution Network Operators (DNOs) (Magnani and Osti, 2016), who may be sole operators in protected markets (see e.g., section 4.1.1 in Hewitt et al., 2017). The obvious solution to this problem is for CE initiatives to become DNOs themselves, and there have been recent such attempts in Germany, and one notable success in the city of Hamburg (Magnani and Osti, 2016).

Our study also shows that successful CE schemes are invariably partnerships between community groups, private companies and particularly, local government. In Southern Europe especially, local government plays a key role in CE. In Spain, citizens' movements have recently taken control of many towns and cities, and begun to develop their own vision of energy transition (e.g., in Cadiz and Barcelona), the waves of “re-municipalization” of local energy supply in Germany have already been mentioned (Wagner and Berlo, 2017). In spite of the relative weakness of local government in the UK, similar movements have begun to emerge there also (e.g., Robin Hood energy; Hiteva and Sovacool, 2017). Thus, the growth of CE from minority activism to mainstream acceptance, eventually accompanied by strong political support in some countries [e.g., in Germany and UK (Scotland)], can be seen as a reflection of the growing understanding by actor communities across public, private and third sectors of the potential benefits to each of them. Many schemes are increasingly public-private-third sector hybrids, with for example, community shares offered by a commercial consortium (UK 7), or PPP schemes with a citizen governing board (SP 19).

Where Next? the Future of CE in Europe

In 2019 it is unclear whether CE will continue to grow as rapidly in future as it has done in the period 2010–16, and there is already some evidence of deceleration in several countries (Table 2; Figure 10). Our study clearly shows that a supportive legal and policy context is important to successful implantation of CE projects, and that in its absence, the development of CE has been seriously constrained, e.g., in Italy, Spain and Poland. In the UK, progress in CE was slow until FiTs were finally introduced, after which they enjoyed a brief golden age until rules were tightened in 2014 and the numbers of new CE initiatives fell. They are likely to fall further when FiTs are removed in 2019. In Italy and Germany, changes to FiTs in 2013 also dramatically affected the CE landscape (Candelise and Ruggieri, 2017; Kahla et al., 2017). In Sweden, low prices, lack of security for investors and a complicated and ambiguous permissions process have led to a decline in new wind power investments since 2015 (Kooij et al., 2018; Wizelius, 2018). Unprofitable CE schemes may sell out to larger suppliers, leading to consolidation in the hands of large companies (Wizelius, 2018). This raises the question to what extent CE can realistically be “upscaled” in a competitive business environment. In case of business failure, citizen buyouts of commercial schemes, such as those in France (e.g., FR 14) can simply be reversed. It is unclear to what extent CE can be protected against the centralizing tendencies of the market without specific legislation in place.

At the same time, however, CE initiatives have proved adept at finding ways around even the most byzantine rules and constraints. Wizelius (2018) notes that wind cooperatives in Sweden did develop, in spite of quite unfavorable conditions. Even though the energy generating coop in the style of Germany or Sweden did not take off in Spain, Spanish REScoops have found an important niche as green energy resellers, and are taking market share from the energy giants. CE innovators are getting wiser, and, increasingly, hybrid strategies are emerging that reduce risk and increase the chances of success, even in the face of indifference and even outright hostility to the sector. In Germany, the shift from the cooperative to the company-based partnership model (GmbH & Co. KG) is one such example, in the UK, the introduction of wholly owned private companies that exist only to sell electricity and distribute returns, leaving their not-for-profit parent organization to concentrate on community development, is another.

The emergence of these new forms in successive waves of innovation (Table 3) can be identified as an adaptive cycle (Cremades et al., 2018). The SI framework proposed here is a useful vehicle for beginning to unpick the inherent complexity that this implies; this is, however, a task that we must leave for future research.

As the recent IPCC report notes (IPCC, 2018), the scale of the remaining challenge to decarbonize energy systems remains huge and, in light of this, governments may prefer to transact deals with large-scale experienced energy producers than a myriad of communitarian initiatives, with its associated high transaction costs. In light of this, the emergence of hybrid structures of joint ownership seems a more likely proposition than a more deeply relocalized and redemocratised energy supply and distribution. This will not stop innovation with regard to new business models and new forms of social innovation, but the challenge to decarbonize rapidly may limit the scope of these alternative approaches which offer so much potential in engaging citizens and empowering communities.

Limitations of the Study and Future Research

The study clearly has some important limitations. In terms of the survey and mapping exercise, although a serious attempt was made to be obtain representative examples of CE from all parts of each country, difficulties of data availability, together with the wide variety of potential definitions of CE mean that there are some notable differences in the nature and quality of the information presented between countries. We feel that this is unavoidable given the scope of our study, but nevertheless, the database of CE initiatives should be considered a starting point for more detailed study, not a definitive statement. In particular, future research is likely to prove fruitful in the following key areas:

• CE in former communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe.

• Enablers and barriers of CE initiatives. There are studies in this field, but they tend to be single country-focused, and up-to-date general reviews of this aspect for the European context are scarce.

• CE financing and economic opportunities for communities. A comparative study of different financing arrangements for community projects, and an evaluation of their attractiveness and level of uptake.

• Spatial analysis of distribution and diffusion of European CE. Can common geographical or socio-economic indicators be identified that drive the development of SI in CE?

• Quantification of the real impact, in terms of energy generation or energy savings, of CE initiatives, compared to mainstream commercial energy generation.

• Research into the potential impact of CE to disrupt markets and challenge the energy multinationals.

• CE networks, e.g., using sociograms (e.g., Alonso et al., 2016), or social network analysis (e.g., Verbong and Geels, 2007).

Conclusions

This research has contributed to developing a more complete picture of a well-studied, but highly fragmented, research area. CE is a very diverse phenomenon, with participation of a large range of private, public, and third sector actors. CE in its various forms is embedded everywhere in Europe except in the former communist countries of the center and east of the continent, and there are some signs of decentralization (if not yet clearly recognizable CE), there too, as evidenced by the recent “energy cluster” initiatives in Poland. It remains to be seen if bona fide examples of CE will emerge there too.

Social Innovation provides a useful framework for analysis of CE projects. Broadly accepted definitions of SI emphasize the importance of specific crises or opportunities to provide the necessary impulse for social change. From this perspective, it is possible to identify three broad phases of CE, each associated with different crises or opportunities. The “oil shocks” of the 1970s offer a clearly identifiable crisis, and the increasingly influential environmental movement provided a social context able to respond to it in innovative ways. These were both social (radical movements for change, new institutions and structures) and technological (experimentation with renewable energy). In Sweden and Germany, cooperatives were renewable energy pioneers, as mainstream sources of capital financing were not initially available.

In the second phase of the innovation cycle, large companies came on board, FiTs and certification schemes were introduced by governments, which increased the viability of community projects but also crowded them out of the marketplace, which was increasingly occupied by large energy firms. The EU directive on energy market liberalization, generous incentives, and a sharp fall in the price of solar technology facilitated CE developments. Nonetheless, in countries with highly centralized or fossil-fuel dependent energy sectors (e.g., Belgium, Poland, France) CE initiatives developed slowly (Belgium), not at all (Poland), or were not really driven by citizens (France). Italy and Spain, despite increasing capacity in renewables, remained at the margins in terms of CE innovation even after the introduction of generous incentives because the niche that CE might have occupied in pioneering renewables (e.g., as it did in northern Europe) had been filled by large companies. In the UK, while incentives for renewables were in place since 1990, they tended to favor larger developers (Cowtan, 2017), and thus the first CE project did not emerge until 1997.

The Great Recession of 2008 marks the beginning of a third wave of innovation in CE. This seems to have been driven by a crisis of acceptance of the “extractivist” development model which large developer-led projects had come to symbolize, in the context of citizens' growing dissatisfaction with rapidly increasing energy prices under a declining economy. This latest phase of innovation is marked by the appearance of new forms of CE, like the CDT model developed in Scotland, the proliferation of supply cooperatives in Spain and Italy, and of a wide range of grassroots energy movements like transition towns, community sustainability initiatives and energy transition “roundtables.”

The last of these three phases is by far the most inclusive and participatory. Unlike Phase I, it is not mainly about persuading other actors (i.e., governments) to “do something,” and unlike Phase II, it does not emphasize cleaner production (i.e., renewable energy) as an end in itself, though this remains an important underlying theme. Instead, it is much more closely tied to citizens' concerns around the democratization and decentralization of energy. It recognizes that energy is not just about electricity, and emphasizes holistic solutions, like waste reduction and the circular economy. It demands that the benefits of energy should be shared more widely. Above all, it fights to redefine energy as a right which citizens should enjoy, rather than as a commodity to be sold to the highest bidder.

Looking to the future, some troubling tendencies can be perceived. The latest boom in CE has slowed, and financial incentives are being removed or reduced. CE has probably reached its peak. In Germany, Sweden and France, it seems likely that REScoops could be absorbed by large companies in a new round of acquisitions and mergers if declining revenues make CE schemes unprofitable. The abolition of the FiT in the UK in 2019 poses a serious threat to the viability of the CDT model pioneered in Scotland. The Spanish supply cooperatives are still growing, but occupy only a very small sector of the electricity market (Capellán-Pérez et al., 2018). In France and Poland the future looks brighter, but it is unclear to what extent citizens are really being engaged in either of these countries. However, CE initiatives in their diverse forms are likely to continue to act as incubators for ideas that are later adopted by the mainstream. In this sense, the focus on sustainability, energy efficiency and fairer distribution of returns that is characteristic of many grassroots CE initiatives today is an encouraging sign.

Author Contributions

The study was conceived by RH, with the support of CB, BS, and NB. NB devised and tested the initial search methodology. RH wrote the article based on detailed surveys of CE in each country and synthetic text provided, for each of the case study countries, by CB (France), NB (Belgium), AB (Italy), RC (Germany), and AC and IMO (Poland). RH carried out the surveys and wrote text for Sweden, UK and Spain. MM Prepared the maps for all case study countries. All authors contributed to revising and editing the text.

Funding

This work was funded by the Rural Affairs and the Environment Strategic Research Program of the Scottish Government, and by the European Commission under the remit of European Union Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation Program grant No. 677622, awarded to the project Social Innovation in Marginalized Rural Areas (SIMRA).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Maria Nijnik and David Miller of the James Hutton Institute for the key role they played in facilitating this work within the remit of the SIMRA project. We would also like to thank Jelte Harnmeijer for his helpful comments on an earlier draft of this manuscript. IMO acknowledges funding from the Earth League alliance and AC acknowledges the financial support of the Stiftung der Deutschen Wirtschaft. We are also very grateful to the editors for their patient handling of our contribution, and to two reviewers whose helpful recommendations led to considerable improvements to our paper.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fenrg.2019.00031/full#supplementary-material

References

Aitken, M. (2010). Why we still don't understand the social aspects of wind power: a critique of key assumptions within the literature. Energy Policy 38, 1834–1841. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2009.11.060

Alonso, P. M., Hewitt, R., Pacheco, J. D., Bermejo, L. R., Jiménez, V. H., Guillén, J. V., et al. (2016). Losing the roadmap: renewable energy paralysis in Spain and its implications for the EU low carbon economy. Renew. Energy 89, 680–694. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2015.12.004

Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Inst. Plann. 35, 216–224. doi: 10.1080/01944366908977225

Barquin, J., Bergman, L., Crampes, C., Glachant, J. M., Green, R., Von Hirschhausen, C., et al. (2006). The acquisition of Endesa by gas natural: why the antitrust authorities are right to be cautious. Electric. J. 19, 62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.tej.2006.01.002

Baur, L., and Uriona, M. (2018). Diffusion of photovoltaic technology in Germany: a sustainable success or an illusion driven by guaranteed feed-in tariffs? Energy 150, 289–298. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2018.02.104

Bauwens, T., and Defourny, J. (2017). Social capital and mutual versus public benefit: the case of renewable energy cooperatives. Ann. Publ. Cooper. Econom. 88, 203–232. doi: 10.1111/apce.12166

Bauwens, T., Gotchev, B., and Holstenkamp, L. (2016). What drives the development of community energy in Europe? The case of wind power cooperatives. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 13, 136–147. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2015.12.016

Becker, S., and Kunze, C. (2014). Transcending community energy: collective and politically motivated projects in renewable energy (CPE) across Europe. People Place Policy Online 8, 180–191. doi: 10.3351/ppp.0008.0003.0004

Becker, S., Kunze, C., and Vancea, M. (2017). Community energy and social entrepreneurship: addressing purpose, organisation and embeddedness of renewable energy projects. J. Clean. Prod. 147, 25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.048

Beckmann, V., Otto, I. M., and Tan, R. (2015). Overcoming the legacy of the past? Analyzing the modes of governance used by the Polish agricultural producer groups. Agric. Econ. 61, 222–233. doi: 10.17221/190/2014-AGRICECON

Bessete, N. (2018). “Vilawatt - An innovative public-private-citizen partnership for energy governance,” in 23 Community-Led Climate Action Initiatives, Report for AEIDL, ed N. Bessete (Brussels, Belgium), 3–4. Available online at: https://www.aeidl.eu/images/stories/pdf/flash/flash59.pdf

Bilgili, M., Yasar, A., and Simsek, E. (2011). Offshore wind power development in Europe and its comparison with onshore counterpart. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 15, 905–915. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2010.11.006