Introduction

Disasters whether natural or man-made, pose major challenge to human health and development in Africa; their impact on the health of individuals and communities are often severe and could hinder attainment of global, regional, and national development goals (1–3). Recent disasters in Africa aptly illustrate the complex interaction between health systems and disasters; a vicious cycle in which weak health systems provide fertile grounds for deterioration of public health and natural hazards into disasters while on the other hand, disasters further decimate already weak health systems (4). The sustained transmission of the 2014/15 Ebola virus disease outbreak in Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone was consistently linked to the weak health systems in these countries (5, 6). The outbreak resulted in the death of several health workers (7), depletion of scarce financial resources, diversion of medical equipment. This in addition to overburdening of already weak health information and supply chain management systems resulted in disruption of health services delivery in these countries (8–10). Other disasters such as the Yellow Fever outbreaks in Angola, Democratic Republic of Congo and Uganda, and ongoing armed conflicts in South Sudan, Central Africa Republic, northeast Nigeria, and other African countries also had similar consequences (11–15). This pattern is not limited to Africa; the fragile pre-disaster health systems in the city of New Orleans in America and the Eastern Visayas Region of the Philippines contributed to the public health consequences of Hurricane Katrina and Haiyan (Yolanda) and constrained timely and effective post-disaster health system recovery efforts (16, 17). The pre-Katrina health system in the city of New Orleans was characterized by low coverage of health insurance and reduced access to health services by the largely poor population of the city (16). Similar challenges such as inadequate health-care infrastructure, staffing, and low coverage of health insurance, which reduced access to health services were also prevalent in the affected areas of the Philippines pre-Hurricane Haiyan (17).

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction (SFDRR) and sustainable development goals (SDGs), both of which are landmark United Nations agreements adopted in 2015, recommend scaling up implementation of disaster risk reduction (DRR) strategies as means to improve resilience to disasters globally (18, 19). The SFDRR in contrast to its predecessor, the Hyogo Framework for Action, puts a lot of emphasis on health (20). It proposes resilient health systems as an opportunity for ensuring effective DRR in the health sector (20). The World Health Assembly, through resolution 64.10, urged countries to strengthen disaster risk management (DRM) programs by incorporating them into national health systems (21). The 2008 Ouagadougou declaration on Primary Health Care and the African Regional strategy for DRM in the health sector also advocated for the use of strong health systems as the basis for addressing the health vulnerabilities and inequalities, which are associated with disasters in Africa (22, 23).

The foregoing and available literatures (2, 24) make a strong case for the use of resilient health systems as a conceptual framework for public health DRM in Africa. Calls for the use of resilient health system as the basis for public health DRM have intensified lately (25); however, there is paucity of practical guidance, requisite tools, and skills for integration of DRM into longer-term health system programs in public health settings in Africa (26). This often results in parallel implementation of health systems strengthening and public health DRM programs within Ministries of Health and between their Disaster Management counterparts with duplication of efforts and lack of synergy. This article reflects on the nexus between the health system framework and DRM and provides insights into how a resilient health system could be used as a framework to strengthen public health DRM in Africa.

The Health System Framework and DRM

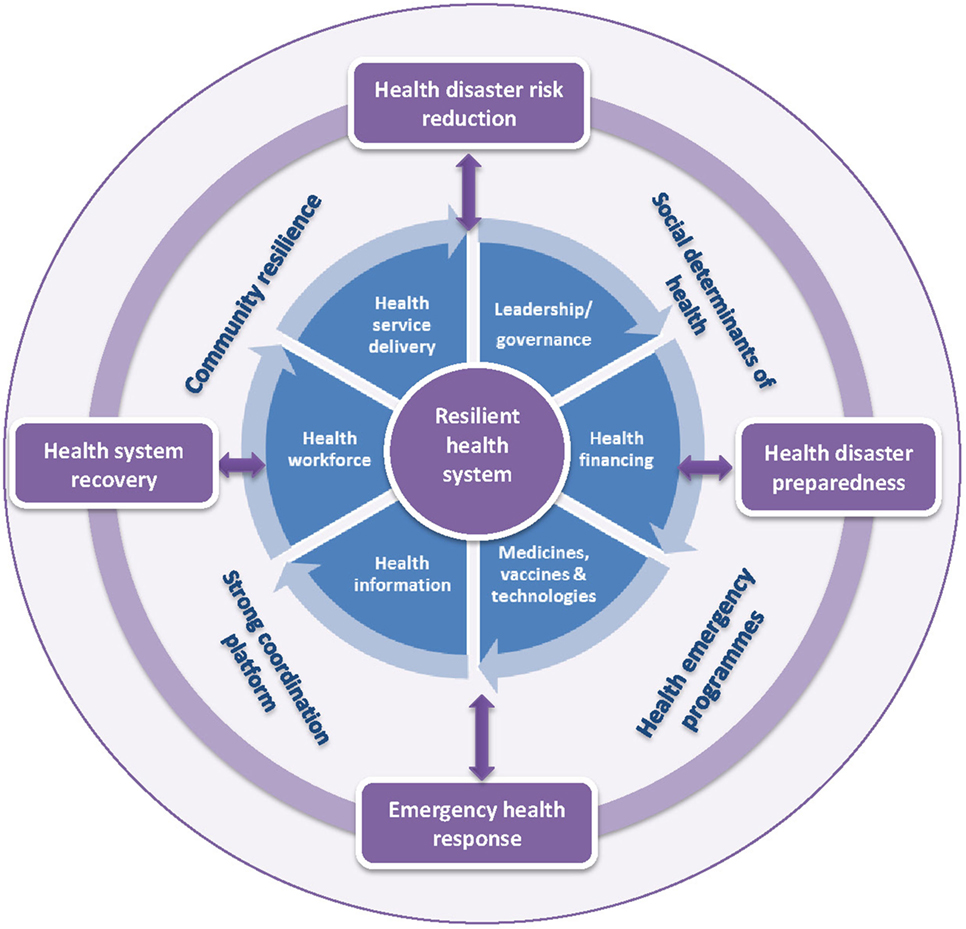

The health system consist of “all organizations, people and actions whose primary intent is to promote, restore, or maintain health” (27), while DRM is defined as the use of administrative and operational procedures to implement interventions aimed at reducing the adverse impact of disaster hazards (28). The health system encompasses all direct health-improving activities implemented either at home, in the community, and the formal health sector level and the social determinants of health, which are the conditions under which people are born, live, and grow. The health system framework comprises six building blocks namely health service delivery, health workforce, health information management system, medical products including vaccines and technologies, health financing, and health leadership and governance (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The health system building blocks as a conceptual framework for public health disaster risk management.

A resilient health system is one which is able to effectively prepare for, withstand the stress of, and respond to the public health consequences of disasters (29). Resilient health systems are able to protect themselves and human lives from the public health impact of disasters and are critical to achieving good health outcomes before, during, and after disasters (26). Kruk et al. defined five elements of resilient health systems (29). Resilient health systems should be aware of the strengths and vulnerability of its building blocks and the spectrum of hazards and risks to which it is exposed. They should be able to respond to a wide range of public health issues before or during a disaster. Health systems should be able to quickly and effectively adapt to changing situations and should use integrated approaches for responding to public health events such as disasters. Last, a resilient health system should be able to regulate itself. These elements provide a good basis for strengthening and using health system for public health DRM.

Resilient Health Systems, Communities, and Social Determinants of Health as Basis for Public Health DRM

Lessons from the West African Ebola outbreak and Hurricanes Katrina and Haiyan show how an emergency situation can deteriorate into a disaster in the face of a weak health system (4, 16, 17). Conversely, resilient health systems could reduce vulnerability to the public health consequences of disasters (4). In the aftermath of a disaster, strong supply chain systems for essential medicines, safe health facilities, and adequate numbers of well-trained health workers would ensure the provision of uninterrupted basic health-care services to disaster affected populations. Functional health information management systems would provide the information required for timely detection and response to presence of biological hazards such as cholera, typhoid fever, watery diarrhea, measles, etc., which often occurs as aftermaths of disasters. Adequate financing of emergency health service programs and strong health governance and oversight systems would ensure that human, financial, and logistics resources are available and utilized to implement well-coordinated DRM strategies to mitigate the public health consequences of the disaster. Good service delivery and coverage of key public health interventions such as immunization, insecticide-treated bed nets, clean water, and improved sanitation would prevent disease outbreaks among disaster-affected populations. These would contribute to good public health outcomes during a disaster.

In practical terms, effective measures to address the public health consequences of droughts such as good immunization coverage, adequate nutrition, and health services delivery including clinical management of severe acute malnutrition, ongoing surveillance of nutrition indicators, and effective risk communication about malnutrition would ensure that such situations do not deteriorate into famines (24). Similarly, safe and well-sited health facilities, good health sector disaster mitigation, contingency and business continuity planning, adequate essential medicines, and supplies for trauma care, and well-trained health staff would ensure that the consequences of earthquakes do not result in major public health disasters (24).

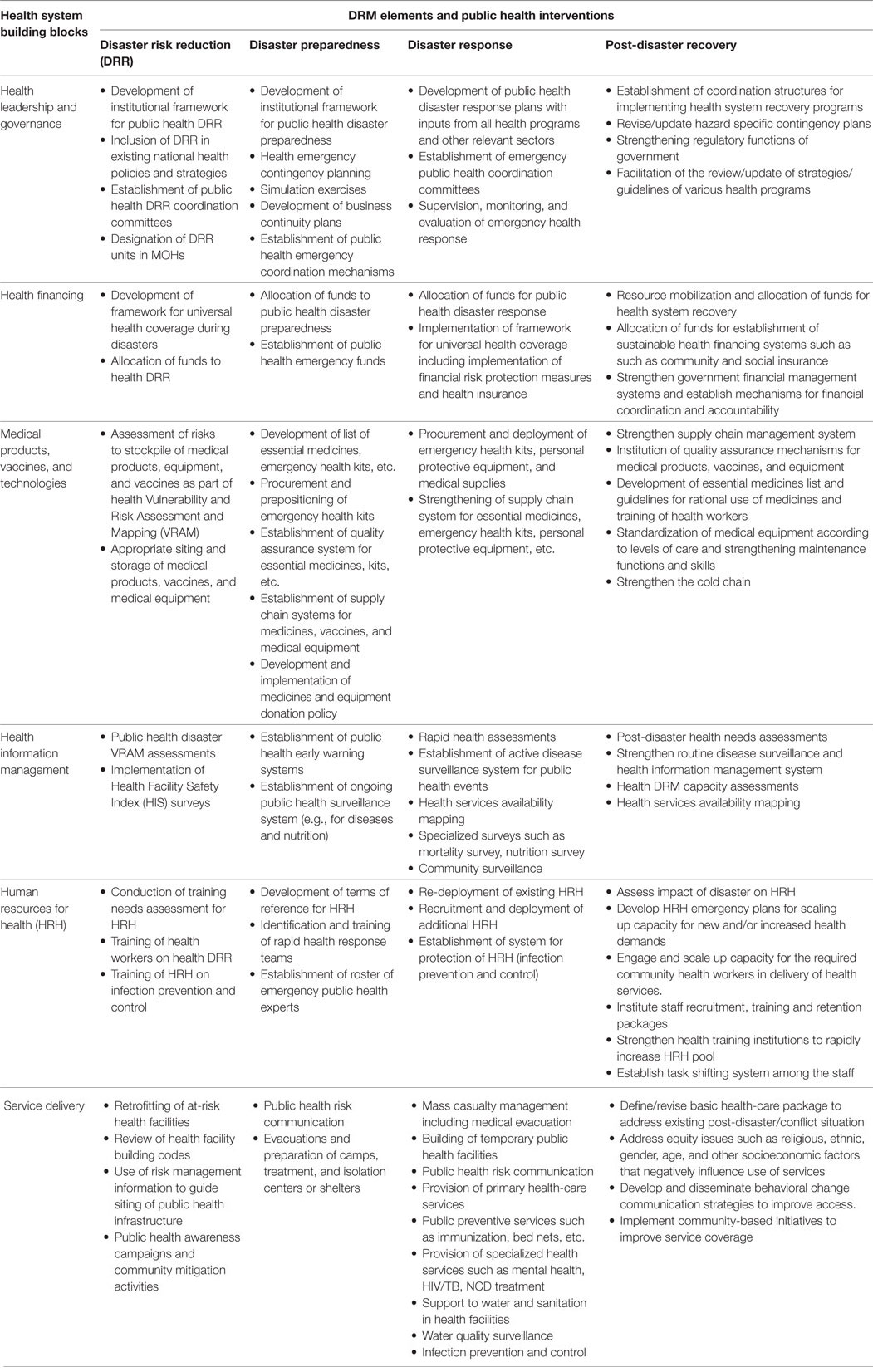

Practical application of resilient health systems as a framework for strengthening public health DRM is, therefore, an imperative in Africa. This requires the strengthening and use of the six health system building blocks as elements in the implementation of public health DRR, preparedness, response and post-disaster recovery interventions at the individual, community, and formal health sector levels (Table 1). Apart from weak health systems, poor status of the social determinants such as poverty, lack of good housing, inadequate access to good nutrition, clean water, improved sanitation, education, and social protection could reduce individual and community resilience and increase the risk of disasters (Figure 1) (2, 30). Thus optimal social determinants of health and resilient communities are also required for mitigating the public health risks and impacts of disasters (2, 31).

Table 1. Application of the health system framework to public health disaster risk management (DRM).

Conclusion

The foregoing points to weak health system as a key factor, which determines public health disaster risk in Africa and similar settings. Public health DRM programs on the continent should, therefore, place resilient health systems at their core. This calls for use of innovative solutions, which are adapted to the African context to build the resilience of health systems and communities. This could be achieved through the use of the five elements proposed by Kruk et al. namely awareness, diversity, self-regulation, integration, and adaptability (29). In addition, the social determinants would also need to be strengthened as basis for reinforcing public health DRM in Africa. Furthermore, African health systems should be protected from the adverse impact of disasters in order to preserve the gains made during the millennium development goal era and contribute to the attainment of global and regional development goals such as the SDG and Africa’s Agenda 2063. These requires a number of actions.

First, African countries should regularly conduct independent assessments of the resilience of their health systems vis-à-vis their capacity for DRM by conducting health vulnerability and risk assessments as part of joint external evaluation of the International Health Regulations core capacities. Second, the countries should develop and implement practical policies, strategies, and guidelines to strengthen health system and community resilience. Integration of DRM strategies into long-term health systems development programs should also be institutionalized. Similarly, health system strengthening strategies should be mainstreamed into public health DRM programs. Third, individual and institutional capacity building to improve the skills and knowledge base for health system resilience building and public health DRM should be scaled up on the continent. Furthermore, guidelines and tools for practical application of resilient health system building blocks as elements in the implementation of public health DRM programs are required. Fourth, the use of multisectoral and multi-disciplinary approach to ensure that the issues of community resilience and social determinants are jointly addressed as part of holistic public health DRM programs is also an imperative. Fifth, operational researches to identify novel mechanisms for applying the health system framework to public health DRM should be intensified. Such researches should also examine the disparities between the health systems in developed and developing countries and whether these translate to real differences in public health outcomes during disasters. Importantly, these actions should be implemented as comprehensive packages, which are integrated into SFDRR and SDGs domestication programs and national health sector policies and strategic plans to ensure coherence, synergy, and sustainability.

Author Contributions

OO is the corresponding author of this manuscript. He solely designed and wrote the work described in it.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The author declares that this manuscript was written in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The author alone is responsible for the views expressed in this article, which do not necessarily represent the views, decisions, or a policy of the institutions with which he is affiliated.

Funding

This manuscript was produced using the author’s personal resources.

Abbreviations

DRM, disaster risk management; SDGs, sustainable development goals; SFDRR, Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction.

References

1. Michailof S, Kostner M, Devictor X. Post-conflict recovery in Africa: an agenda for the African region. Africa Region Working Paper Series No 30. World Bank. (2002). Available from: http://www.sergemichailof.fr/wp-content/uploads/2010/02/postconflictrecoveryinafrica2002.pdf

2. Dar O, Buckley EJ, Rokadiya S, Huda Q, Abrahams J. Integrating health into disaster risk reduction strategies: key considerations for success. Am J Public Health (2014) 104(10):1811–6. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302134

3. Lamptey BJ, Awojobi ON. The spread of the Ebola virus disease and its implications in the West African sub-region. Int J Innov Sci Res (2014) 11(1):130–43.

4. Kieny MP, Evans DB, Schmets G, Kadandale S. Health-system resilience: reflections on the Ebola crisis in western Africa. Bull World Health Organ (2014) 92(12):850. doi:10.2471/BLT.14.149278

5. Kieny MP, Dovlo D. Beyond Ebola: a new agenda for resilient health systems. Lancet (2015) 385(9963):91–2. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(14)62479-X

6. Cancedda C, Davis SM, Dierberg KL, Lascher J, Kelly JD, Barrie MB, et al. Strengthening health systems while responding to a health crisis: lessons learned by a nongovernmental organization during the Ebola virus disease epidemic in Sierra Leone. J Infect Dis (2016) 214(Suppl 3):S153–63. doi:10.1093/infdis/jiw345

7. Health Worker Ebola Infections in Guinea. Liberia and Sierra Leone – A Preliminary Report. World Health Organization (2015). Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/171823/1/WHO_EVD_SDS_REPORT_2015.1_eng.pdf?ua=1&ua=1

8. Brolin Ribacke KJ, Saulnier DD, Eriksson A, von Schreeb J. Effects of the West Africa Ebola virus disease on health-care utilization – a systematic review. Front Public Health (2016) 4:222. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2016.00222

9. Elston JW, Cartwright C, Ndumbi P, Wright J. The health impact of the 2014–15 Ebola outbreak. Public Health (2017) 143:60–70. doi:10.1016/j.puhe.2016.10.020

10. Bolkan HA, Bash-Taqi DA, Samai M, Gerdin M, von Schreeb J. Ebola and indirect effects on health service function in Sierra Leone. PLoS Curr (2014) 6. doi:10.1371/currents.outbreaks.0307d588df619f9c9447f8ead5b72b2d

11. Green A. Yellow fever continues to spread in Angola. Lancet (2016) 387(10037):2493. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30835-2

12. Nishino K, Yactayo S, Garcia E, Aramburu GJ, Manuel E, Costa A, et al. Yellow fever urban outbreak in Angola and the risk of extension. Wkly Epidemiol Rec (2016) 91(14):186–92.

13. Jones A, Howard N, Legido-Quigley H. Feasibility of health systems strengthening in South Sudan: a qualitative study of international practitioner perspectives. BMJ Open (2015) 5:e009296. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009296

14. Central African Republic Crisis and Its Regional Humanitarian Impact. United Nations Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (UNOCHA). (2014). Available from: https://www.humanitarianresponse.info/system/files/documents/files/Central%20African%20Republic%20Crisis%20and%20its%20Regional%20Humanitarian%20Impact%20June%202014.pdf

15. Omole O, Welye H, Abimbola S. Boko Haram insurgency: implications for public health. Lancet (2015) 385(9972):941. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60207-0

16. Rudowitz R, Rowland D, Shartzer A. Health care in New Orleans before and after hurricane Katrina. Health Aff (2006) 25(5):w393–406. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.25.w393

17. Casamina C, Lee C, Reyes R. Tropical cyclone Haiyan/Yolanda medical relief mission: perspectives of John A Bums School of Medicine 2nd year medical students. Hawaii J Med Public Health (2015) 74(5):176–8.

18. Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 2015–2030. (2015). Available from: http://www.unisdr.org/we/coordinate/sendai-framework

19. Sustainable Development Goal 3: Ensure Healthy Lives and Promote Well-Being for All at All Ages. (2016). Available from: http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/

20. Aitsi-Selmi A, Murray V. Protecting the health and well-being of populations from disasters: health and health care in the Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction 2015–2030. Prehosp Disaster Med (2016) 31(1):74–8. doi:10.1017/S1049023X15005531

21. World Health Assembly Resolution. (2011). Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/3566

22. Disaster Risk Management: A Strategy for the Health Sector in the African Region. Report of the Secretariat. World Health Organization, Regional Committee for Africa. Luanda, Republic of Angola: World Health Organization (WHO) (2012). Available from: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/80238/1/AFR-RC62-6-e.pdf

23. Barry SP, Somanje H, Kirigia JM, Nyoni J, Bessaoud K, Trapsida JM, et al. The Ouagadougou declaration on primary health care and health systems in Africa: achieving better health for Africa in the new millennium. African Health Monit (2010) (12). Available from: https://www.aho.afro.who.int/en/ahm/issue/12/reports/ouagadougou-declaration-primary-health-care-and-health-systems-africa-achieving

24. Bayntun C, Rockenschaub G, Murray V. Developing a health system approach to disaster management: a qualitative analysis of the core literature to complement the WHO Toolkit for assessing health-system capacity for crisis management. PLoS Curr (2012) 4:e5028b6037259a. doi:10.1371/5028b6037259a

25. Aitsi-Selmi A, Murray V. The Sendai framework: disaster risk reduction through a health lens. Bull World Health Organ (2015) 93(6):362. doi:10.2471/BLT.15.157362

26. Bayntun C. A health system approach to all-hazards disaster management: a systematic review. PLoS Curr (2012) 4:e50081cad5861d. doi:10.1371/50081cad5861d

27. Everybody’s Business. Strengthening Health Systems to Improve Health Outcomes; WHO’s Framework for Action. World Health Organization (WHO) (2007). Available from: http://www.who.int/healthsystems/strategy/everybodys_business.pdf

28. UNISDR Terminology on Disaster Reduction. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNISDR). (2009). Available from: http://www.unisdr.org/files/7817_UNISDRTerminologyEnglish.pdf

29. Kruk ME, Myers M, Varpilah ST, Dahn BT. What is a resilient health system? Lessons from Ebola. Lancet (2015) 385(9980):1910–2. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60755-3

30. Acharya M. Ebola virus disease outbreak – 2014: implications and pitfalls. Front Public Health (2014) 2:263. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2014.00263

Keywords: resilient health system, public health, disaster risk management, conceptual framework, Africa, opinion article

Citation: Olu O (2017) Resilient Health System As Conceptual Framework for Strengthening Public Health Disaster Risk Management: An African Viewpoint. Front. Public Health 5:263. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00263

Received: 22 May 2017; Accepted: 14 September 2017;

Published: 28 September 2017

Edited by:

Steven Joseph Phillips, National Institutes of Health, United StatesReviewed by:

Gerlant van Berlaer, Universitair Ziekenhuis Brussel, BelgiumCopyright: © 2017 Olu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Olushayo Olu, oluo@who.int

Olushayo Olu

Olushayo Olu