Human Body Rhythms in the Development of Non-Invasive Methods of Closed-Loop Adaptive Neurostimulation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

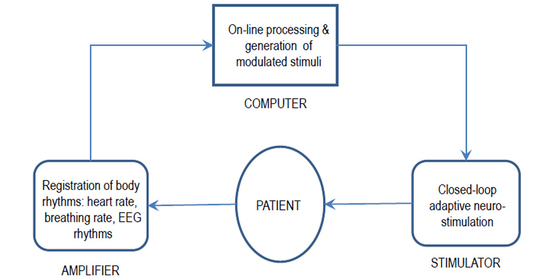

2. Benefits of Closed-Loop Systems

3. Human Endogenous Rhythms as Modulating Factor for Sensory Stimulation

4. Recently Developed Methods of Closed-Loop Adaptive Neurostimulation

5. Conclusions

- –

- High personalization through the use of closed-loop feedback from the patient’s own bioelectric characteristics;

- –

- Involvement of interoceptive signals in the mechanisms of multisensory integration, neuroplasticity, and resonance mechanisms of the brain;

- –

- Automatic operation, without conscious efforts of an individual, and control of therapeutic sensory stimulation, which makes it possible to use adaptive neurostimulation to correct functional disturbances in patients with altered levels of consciousness independently from their motivation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Klooster, D.D.; De Louw, A.A.; Aldenkamp, A.A.; Besseling, R.R.; Mestrom, R.R.; Carrette, E.E.; Zinger, S.S.; Bergmans, J.J.; Mess, W.W.; Vonck, K.; et al. Technical aspects of neurostimulation: Focus on equipment, electric field modeling, and stimulation protocols. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2016, 65, 113–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansouri, F.; Fettes, P.; Schulze, L.; Giacobbe, P.; Zariffa, J.; Downar, J. A Real-Time Phase-Locking System for Non-invasive Brain Stimulation. Front. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terranova, C.; Rizzo, V.; Cacciola, A.; Chillemi, G.; Calamuneri, A.; Milardi, D.; Quartarone, A. Is There a Future for Non-invasive Brain Stimulation as a Therapeutic Tool? Front. Neurol. 2019, 9, 1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vosskuhl, J.; Strüber, D.; Herrmann, C.S. Non-invasive Brain Stimulation: A Paradigm Shift in Understanding Brain Oscillations. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Draaisma, L.R.; Wessel, M.J.; Hummel, F.C. Non-invasive brain stimulation to enhance cognitive rehabilitation after stroke. Neurosci. Lett. 2020, 719, 133678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufmann, T.; Holz, E.M.; Kübler, A. Comparison of tactile, auditory, and visual modality for brain-computer interface use: A case study with a patient in the locked-in state. Front. Neurosci. 2013, 7, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Noda, Y.; Barr, M.; Zomorrodi, R.; Cash, R.; Lioumis, P.; Chen, R.; Daskalakis, Z.; Blumberger, D. Single-Pulse Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation-Evoked Potential Amplitudes and Latencies in the Motor and Dorsolateral Prefrontal Cortex among Young, Older Healthy Participants, and Schizophrenia Patients. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, C.A.; Kouzani, A.; Lee, K.H.; Ross, E.K. Neurostimulation Devices for the Treatment of Neurologic Disorders. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2017, 92, 1427–1444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zanos, S. Closed-Loop Neuromodulation in Physiological and Translational Research. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Med. 2018, 9, a034314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oxley, T.; Opie, N. Closed-Loop Neuromodulation: Listen to the Body. World Neurosurg. 2019, 122, 415–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, M.-C.; Widge, A.S. Closed-loop neuromodulation systems: Next-generation treatments for psychiatric illness. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2017, 29, 191–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shakeel, A.; Onojima, T.; Tanaka, T.; Kitajo, K. Real-Time Implementation of EEG Oscillatory Phase-Informed Visual Stimulation Using a Least Mean Square-Based AR Model. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, F.T.; Morrell, M.J. Closed-loop Neurostimulation: The Clinical Experience. Neurotherapeutics 2014, 11, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Biasiucci, A.; Leeb, R.; Iturrate, I.; Perdikis, S.; Al-Khodairy, A.; Corbet, T.; Schnider, A.; Schmidlin, T.; Zhang, H.; Bassolino, M.; et al. Brain-actuated functional electrical stimulation elicits lasting arm motor recovery after stroke. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.H.; Yoon, H.; Jin, H.W.; Bin Kwon, H.; Oh, S.M.; Lee, Y.J.; Park, K.S. Effect of Closed-Loop Vibration Stimulation on Heart Rhythm during Naps. Sensors 2019, 19, 4136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Edelman, B.J.; Meng, J.; Suma, D.; Zurn, C.; Nagarajan, E.; Baxter, B.S.; Cline, C.C.; He, B. Noninvasive neuroimaging enhances continuous neural tracking for robotic device control. Sci. Robot. 2019, 4, eaaw6844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faller, J.; Cummings, J.; Saproo, S.; Sajda, P. Regulation of arousal via online neurofeedback improves human performance in a demanding sensory-motor task. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 6482–6490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Papo, D. Neurofeedback: Principles, appraisal, and outstanding issues. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2019, 49, 1454–1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fallani, F.D.V.; Bassett, D.S. Network neuroscience for optimizing brain–computer interfaces. Phys. Life Rev. 2019, 31, 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Price, J.B.; Rusheen, A.E.; Barath, A.S.; Cabrera, J.M.R.; Shin, H.; Chang, S.-Y.; Kimble, C.J.; Bennet, K.E.; Blaha, C.D.; Lee, K.H.; et al. Clinical applications of neurochemical and electrophysiological measurements for closed-loop neurostimulation. Neurosurg. Focus 2020, 49, E6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedotchev, A.I. Endogenous body rhythms as a factor of modulation of the parameters of stimulation. Biophisics 1996, 41, 721–725. [Google Scholar]

- Salansky, N.; Fedotchev, A.; Bondar, A. Responses of the Nervous System to Low Frequency Stimulation and EEG Rhythms: Clinical Implications. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 1998, 22, 395–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riganello, F.; Prada, V.; Soddu, A.; Di Perri, C.; Sannita, W.G. Circadian Rhythms and Measures of CNS/Autonomic Interaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 2336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Haegens, S.; Golumbic, E.Z. Rhythmic facilitation of sensory processing: A critical review. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2018, 86, 150–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abiri, R.; Borhani, S.; Sellers, E.W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, X. A comprehensive review of EEG-based brain–computer interface paradigms. J. Neural Eng. 2018, 16, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quadt, L.; Critchley, H.D.; Garfinkel, S.N. The neurobiology of interoception in health and disease. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2018, 1428, 112–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedotchev, A.I.; Kim, E.V. Correction of functional disturbances during pregnancy by the method of adaptive EEG biofeedback training. Hum. Physiol. 2006, 32, 652–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.; Han, E.; Kushki, A.; Anagnostou, E.; Biddiss, E. Biomusic: An Auditory Interface for Detecting Physiological Indicators of Anxiety in Children. Front. Neurosci. 2016, 10, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deuel, T.A.; Pampin, J.; Sundstrom, J.; Darvas, F. The Encephalophone: A Novel Musical Biofeedback Device using Conscious Control of Electroencephalogram (EEG). Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2017, 11, 213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tegeler, C.H.; Cook, J.F.; Tegeler, C.L.; Hirsch, J.R.; Shaltout, H.A.; Simpson, S.L.; Fidali, B.C.; Gerdes, L.; Lee, S.W. Clinical, hemispheric, and autonomic changes associated with use of closed-loop, allostatic neurotechnology by a case series of individuals with self-reported symptoms of post-traumatic stress. BMC Psychiatry 2017, 17, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yu, B.; Funk, M.; Hu, J.; Feijs, L. Unwind: A musical biofeedback for relaxation assistance. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2018, 37, 800–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shaltout, H.A.; Lee, S.W.; Tegeler, C.L.; Hirsch, J.R.; Simpson, S.L.; Gerdes, L.; Tegeler, C.H. Improvements in Heart Rate Variability, Baroreflex Sensitivity, and Sleep After Use of Closed-Loop Allostatic Neurotechnology by a Heterogeneous Cohort. Front. Public Health 2018, 6, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fedotchev, A.; Radchenko, G.; Zemlianaia, A. On one approach to health protection: Music of the brain. J. Integr. Neurosci. 2018, 17, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ketz, N.; Jones, A.P.; Bryant, N.B.; Clark, V.P.; Pilly, P.K. Closed-Loop Slow-Wave tACS Improves Sleep-Dependent Long-Term Memory Generalization by Modulating Endogenous Oscillations. J. Neurosci. 2018, 38, 7314–7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fedotchev, A.I. Stress coping via musical neurofeedback. Adv. Mind-Body Med. 2018, 32, 22–25. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrlich, S.K.; Agres, K.R.; Guan, C.; Cheng, G. A closed-loop, music-based brain-computer interface for emotion mediation. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0213516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fedotchev, A.I.; Parin, S.B.; Polevaya, S.A.; Zemlianaia, A.A. Effects of Audio–Visual Stimulation Automatically Controlled by the Bioelectric Potentials from Human Brain and Heart. Hum. Physiol. 2019, 45, 523–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegeler, C.L.; Shaltout, H.A.; Lee, S.W.; Simpson, S.L.; Gerdes, L.; Tegeler, C.H. Pilot Trial of a Noninvasive Closed-Loop Neurotechnology for Stress-Related Symptoms in Law Enforcement: Improvements in Self-Reported Symptoms and Autonomic Function. Glob. Adv. Health Med. 2020, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fedotchev, A.; Parin, S.; Savchuk, L.; Polevaya, S. Mechanisms of Light and Music Stimulation Controlled by a Person’s Own Brain and Heart Biopotentials or Those of Another Person. Sovrem. Teh. Med. 2020, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffont, I.; Bella, S.D. Music, rhythm, rehabilitation and the brain: From pleasure to synchronization of biological rhythms. Ann. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2018, 61, 363–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brancatisano, O.; Baird, A.; Thompson, W.F. Why is music therapeutic for neurological disorders? The Therapeutic Music Capacities Model. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2020, 112, 600–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bazanova, O.; Vernon, D. Interpreting EEG alpha activity. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2014, 44, 94–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gentsch, A.; Sel, A.; Marshall, A.C.; Schütz-Bosbach, S. Affective interoceptive inference: Evidence from heart-beat evoked brain potentials. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2019, 40, 20–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Gibson, J. Mindfulness, Interoception, and the Body: A Contemporary Perspective. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Khalsa, S.S.; Adolphs, R.; Cameron, O.G.; Critchley, H.D.; Davenport, P.W.; Feinstein, J.S.; Feusner, J.D.; Garfinkel, S.N.; Lane, R.D.; Mehling, W.E.; et al. Interoception and Mental Health: A Roadmap. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 2018, 3, 501–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Condition | Stimulation | Modulating Rhythm | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Musculoskeletal pain reduction | Electrical stimuli | Breathing rate | Fedotchev 1996 [21] |

| Correction of functional disturbances during pregnancy | Classical music | Theta, alpha, beta EEG rhythms | Fedotchev, Kim 2006 [27] |

| Anxiety reduction | Music-like stimuli | Heart rate, breathing rate | Cheung et al. 2016 [28] |

| Treatment of movement disorders | Music-like stimuli | Alpha or mu EEG rhythms | Deuel et al. 2017 [29] |

| Post-traumatic stress reduction | Acoustic stimuli | Selected EEG frequencies | Tegeler et al. 2017 [30] |

| Relaxation assistance | Music-like stimuli | Heart rate | Yu et al. 2018 [31] |

| Remediation of health concerns | Acoustic stimuli | Selected EEG frequencies | Shaltout et al. 2018 [32] |

| Health protection | Music-like stimuli | Alpha-EEG oscillator | Fedotchev et al. 2018 [33] |

| Improving consolidation of recent experiences into long-term memory | Transcranial alternating current stimulation | Endogenous slow-wave oscillations | Ketz et al. 2018 [34] |

| Stress-induced state correction | Classical music | Alpha-EEG oscillator | Fedotchev 2018 [35] |

| Emotional state correction | Music-like stimuli | Theta, alpha, beta, gamma EEG rhythms | Ehrlich et al. 2019 [36] |

| Stress-induced state correction | Music-like stimuli + photic stimuli | Alpha-EEG oscillator + heart rate + native EEG | Fedotchev et al. 2019 [37] |

| Stress-related symptom reduction | Acoustic stimuli | Selected EEG frequencies | Tegeler et al. 2020 [38] |

| Stress-induced state correction | Music-like stimuli + photic stimuli | Alpha-EEG oscillator + heart rate + native EEG | Fedotchev et al. 2020 [39] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fedotchev, A.; Parin, S.; Polevaya, S.; Zemlianaia, A. Human Body Rhythms in the Development of Non-Invasive Methods of Closed-Loop Adaptive Neurostimulation. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 437. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/jpm11050437

Fedotchev A, Parin S, Polevaya S, Zemlianaia A. Human Body Rhythms in the Development of Non-Invasive Methods of Closed-Loop Adaptive Neurostimulation. Journal of Personalized Medicine. 2021; 11(5):437. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/jpm11050437

Chicago/Turabian StyleFedotchev, Alexander, Sergey Parin, Sofia Polevaya, and Anna Zemlianaia. 2021. "Human Body Rhythms in the Development of Non-Invasive Methods of Closed-Loop Adaptive Neurostimulation" Journal of Personalized Medicine 11, no. 5: 437. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/jpm11050437