Advances in Antifungal Drug Development: An Up-To-Date Mini Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Clinically Used Antifungals

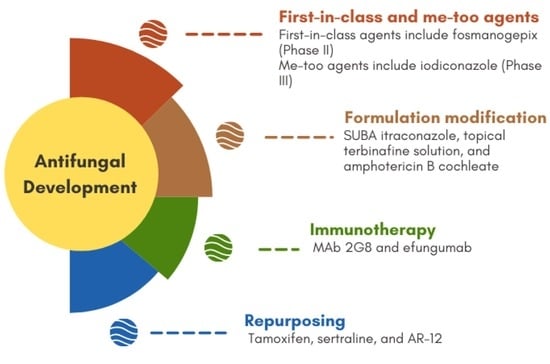

3. Novel Antifungals (In Clinical Settings)

3.1. Aryldiamidines—T-2307

3.2. Fosmanogepix and Manogepix

3.3. Nikkomycin Z

3.4. Orotomides—Olorofim

3.5. Cyclic Peptides—VL-2397

3.6. Cyclic Peptides—Aureobasidin A

3.7. MGCD290

3.8. Tetrazoles

3.9. Triterpenoids—Ibrexafungerp

3.10. Triazoles

3.11. BSG005

3.12. Cyclic Peptides—Rezafungin

3.13. SUBA Itraconazole

3.14. Topical Terbinafine Solution

3.15. Amphotericin B Cochleate

3.16. Metal Complexes and Chelates

4. New Compounds as Potential Antifungals (In Preclinical Stages)

5. Repurposing

6. Immunotherapy

7. New Promising Targets for Antifungal Development

8. Conclusions and Remarks

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chowdhary, A.; Tarai, B.; Singh, A.; Sharma, A. Multidrug-Resistant Candida auris Infections in Critically Ill Coronavirus Disease Patients, India, April–July 2020. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2020, 26, 2694–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boral, H.; Metin, B.; Dogen, A.; Seyedmousavi, S.; Ilkit, M. Overview of selected virulence attributes in Aspergillus fumigants, Candida albicans, Cryptococcus neoformans, Trichophyton rubrum, and Exophiala dermatitidis. Fungal Genet. Biol. 2018, 111, 92–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, H.; Bing, J.; Hu, T.R.; Ennis, C.L.; Nobile, C.J.; Huang, G.H. Candida auris: Epidemiology, biology, antifungal resistance, and virulence. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Odds, F.C.; Brown, A.J.; Gow, N.A. Antifungal agents: Mechanisms of action. Trends Microbiol. 2003, 11, 272–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pienaar, E.D.; Young, T.; Holmes, H. Interventions for the prevention and management of oropharyngeal candidiasis associated with HIV infection in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010, 2010, CD003940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermes, A.; Guchelaar, H.J.; Dankert, J. Flucytosine: A review of its pharmacology, clinical indications, pharmacokinetics, toxicity and drug interactions. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2000, 46, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emri, T.; Majoros, L.; Toth, V.; Pocsi, I. Echinocandins: Production and applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 97, 3267–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maligie, M.A.; Selitrennikoff, C.P. Cryptococcus neoformans resistance to echinocandins: (1,3)beta-glucan synthase activity is sensitive to echinocandins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 2851–2856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ciaravino, V.; Coronado, D.; Lanphear, C.; Shaikh, I.; Ruddock, W.; Chanda, S. Tavaborole, a novel boron-containing small molecule for the topical treatment of onychomycosis, is noncarcinogenic in 2-year carcinogenicity studies. Int. J. Toxicol. 2014, 33, 419–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, H.; Sakagami, T.; Yamada, E.; Fukuda, Y.; Hayakawa, H.; Nomura, N.; Mitsuyama, J.; Miyazaki, T.; Mukae, H.; Kohno, S. T-2307, a novel arylamidine, is transported into Candida albicans nby a high-affinity spermine and spermidine carrier regulated by Agp2. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 1845–1855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yamada, E.; Nishikawa, H.; Nomura, N.; Mitsuyama, J. T-2307 Shows Efficacy in a Murine Model of Candida glabrata Infection despite In Vitro Trailing Growth Phenomena. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 3630–3634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wiederhold, N.P. Review of T-2307, an Investigational Agent That Causes Collapse of Fungal Mitochondrial Membrane Potential. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mann, P.A.; McLellan, C.A.; Koseoglu, S.; Si, Q.; Kuzmin, E.; Flattery, A.; Harris, G.; Sher, X.; Murgolo, N.; Wang, H.; et al. Chemical Genomics-Based Antifungal Drug Discovery: Targeting Glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI) Precursor Biosynthesis. ACS Infect. Dis. 2015, 1, 59–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamoto, K.; Tsukada, I.; Tanaka, K.; Matsukura, M.; Haneda, T.; Inoue, S.; Murai, N.; Abe, S.; Ueda, N.; Miyazaki, M.; et al. Synthesis and evaluation of novel antifungal agents-quinoline and pyridine amide derivatives. Bioorganic Med. Chem. Lett. 2010, 20, 4624–4626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, N.A.; Miyazaki, M.; Horii, T.; Sagane, K.; Tsukahara, K.; Hata, K. E1210, a new broad-spectrum antifungal, suppresses Candida albicans hyphal growth through inhibition of glycosylphosphatidylinositol biosynthesis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 56, 960–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shaw, K.J.; Ibrahim, A.S. Fosmanogepix: A Review of the First-in-Class Broad Spectrum Agent for the Treatment of Invasive Fungal Infections. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hector, R.F.; Pappagianis, D. Inhibition of Chitin Synthesis in the Cell-Wall of Coccidioides-Immitis by Polyoxin-D. J. Bacteriol. 1983, 154, 488–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fortwendel, J.R.; Juvvadi, P.R.; Pinchai, N.; Perfect, B.Z.; Alspaugh, J.A.; Perfect, J.R.; Steinbach, W.J. Differential Effects of Inhibiting Chitin and 1,3-beta-D-Glucan Synthesis in Ras and Calcineurin Mutants of Aspergillus fumigatus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Larwood, D.J. Nikkomycin Z-Ready to Meet the Promise? J. Fungi 2020, 6, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, J.D.; Sibley, G.; Beckmann, N.; Dobb, K.S.; Slater, M.J.; McEntee, L.; du Pré, S.; Livermore, J.; Bromley, M.J.; Wiederhold, N.P.; et al. F901318 represents a novel class of antifungal drug that inhibits dihydroorotate dehydrogenase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2016, 113, 12809–12814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Negri, C.E.; Johnson, A.; McEntee, L.; Box, H.; Whalley, S.; Schwartz, J.A.; Ramos-Martín, V.; Livermore, J.; Kolamunnage-Dona, R.; Colombo, A.L.; et al. Pharmacodynamics of the Novel Antifungal Agent F901318 for Acute Sinopulmonary Aspergillosis Caused by Aspergillus flavus. J. Infect. Dis. 2018, 217, 1118–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiederhold, N.P. Review of the Novel Investigational Antifungal Olorofim. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, I.; Kanasaki, R.; Yoshikawa, K.; Furukawa, S.; Fujie, A.; Hamamoto, H.; Sekimizu, K. Discovery of a new antifungal agent ASP2397 using a silkworm model of Aspergillus fumigatus infection. J. Antibiot. (Tokyo) 2017, 70, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, I.; Ohsumi, K.; Takeda, S.; Katsumata, K.; Matsumoto, S.; Akamatsu, S.; Mitori, H.; Nakai, T. ASP2397 Is a Novel Natural Compound That Exhibits Rapid and Potent Fungicidal Activity against Aspergillus Species through a Specific Transporter. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e02689-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikai, K.; Takesako, K.; Shiomi, K.; Moriguchi, M.; Umeda, Y.; Yamamoto, J.; Kato, I.; Naganawa, H. Structure of aureobasidin A. J. Antibiot. 1991, 44, 925–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqaisi, A.; Mbekeani, A.J.; Llorens, M.B.; Elhammer, A.P.; Denny, P.W. The antifungal Aureobasidin A and an analogue are active against the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii but do not inhibit sphingolipid biosynthesis—Corrigendum. Parasitology 2018, 145, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kurome, T.; Inoue, T.; Takesako, K.; Kato, I.; Inami, K.; Shiba, T. Syntheses of antifungal aureobasidin A analogs with alkyl chains for structure-activity relationship. J. Antibiot. 1998, 51, 359–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Messer, S.A.; Georgopapadakou, N.; Martell, L.A.; Besterman, J.M.; Diekema, D.J. Activity of MGCD290, a Hos2 Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor, in Combination with Azole Antifungals against Opportunistic Fungal Pathogens. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2009, 47, 3797–3804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Cowen, L.E. The fungal Achilles’ heel: Targeting Hsp90 to cripple fungal pathogens. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2013, 16, 377–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Rhomberg, P.R.; Messer, S.A.; Castanheira, M. In vitro activity of a Hos2 deacetylase inhibitor, MGCD290, in combination with echinocandins against echinocandin-resistant Candida species. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2015, 81, 259–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoekstra, W.J.; Garvey, E.P.; Moore, W.R.; Rafferty, S.W.; Yates, C.M.; Schotzinger, R.J. Design and optimization of highly-selective fungal CYP51 inhibitors. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2014, 24, 3455–3458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.X.; Li, L.P.; Lv, Q.Z.; Yan, L.; Wang, Y.; Jiang, Y.Y. The Fungal CYP51s: Their Functions, Structures, Related Drug Resistance, and Inhibitors. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrilow, A.G.S.; Parker, J.E.; Price, C.L.; Nes, W.D.; Garvey, E.P.; Hoekstra, W.J.; Schotzinger, R.J.; Kelly, D.E.; Kelly, S.L. The Investigational Drug VT-1129 Is a Highly Potent Inhibitor of Cryptococcus Species CYP51 but Only Weakly Inhibits the Human Enzyme. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 4530–4538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Garvey, E.P.; Hoekstra, W.J.; Schotzinger, R.J.; Sobel, J.D.; Lilly, E.A.; Fidel, P.L., Jr. Efficacy of the Clinical Agent VT-1161 against Fluconazole-Sensitive and -Resistant Candida albicans in a Murine Model of Vaginal Candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 5567–5573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wiederhold, N.P.; Lockhart, S.R.; Najvar, L.K.; Berkow, E.L.; Jaramillo, R.; Olivo, M.; Garvey, E.P.; Yates, C.M.; Schotzinger, R.J.; Catano, G.; et al. The Fungal Cyp51-Specific Inhibitor VT-1598 Demonstrates In Vitro and In Vivo Activity against Candida auris. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2019, 63, e02233-18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bowman, J.C.; Hicks, P.S.; Kurtz, M.B.; Rosen, H.; Schmatz, D.M.; Liberator, P.A.; Douglas, C.M. The antifungal echinocandin caspofungin acetate kills growing cells of Aspergillus fumigatus in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2002, 46, 3001–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Odds, F.C. Drug evaluation: BAL-8557—A novel broad-spectrum triazole antifungal. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs 2006, 7, 766–772. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schmitt-Hoffmann, A.; Roos, B.; Heep, M.; Schleimer, M.; Weidekamm, E.; Brown, T.; Roehrle, M.; Beglinger, C. Single-ascending-dose pharmacokinetics and safety of the novel broad-spectrum antifungal triazole BAL4815 after intravenous infusions (50, 100, and 200 milligrams) and oral administrations (100, 200, and 400 milligrams) of its prodrug, BAL8557, in healthy volunteers. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 279–285. [Google Scholar]

- Bartroli, J.; Turmo, E.; Algueró, M.; Boncompte, E.; Vericat, M.L.; Conte, L.; Ramis, J.; Merlos, M.; García-Rafanell, J.; Forn, J. New azole antifungals. 2. Synthesis and antifungal activity of heterocyclecarboxamide derivatives of 3-amino-2-aryl-1-azolyl-2-butanol. J. Med. Chem. 1998, 41, 1855–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, N.; Xie, Y.; Sheng, C.; Cao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Chen, H.; Fan, G. In vivo pharmacokinetics and in vitro antifungal activity of iodiconazole, a new triazole, determined by microdialysis sampling. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2013, 41, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brautaset, T.; Sletta, H.; Degnes, K.F.; Sekurova, O.N.; Bakke, I.; Volokhan, O.; Andreassen, T.; Ellingsen, T.E.; Zotchev, S.B. New nystatin-related antifungal polyene macrolides with altered polyol region generated via biosynthetic engineering of Streptomyces noursei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 6636–6643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Krishnan, B.R.; James, K.D.; Polowy, K.; Bryant, B.J.; Vaidya, A.; Smith, S.; Laudeman, C.P. CD101, a novel echinocandin with exceptional stability properties and enhanced aqueous solubility. J. Antibiot. 2017, 70, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ong, V.; James, K.D.; Smith, S.; Krishnan, B.R. Pharmacokinetics of the Novel Echinocandin CD101 in Multiple Animal Species. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e01626-16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Y.; Prideaux, B.; Nagasaki, Y.; Lee, M.H.; Chen, P.Y.; Blanc, L.; Ho, H.; Clancy, C.J.; Nguyen, M.H.; Dartois, V.; et al. Unraveling Drug Penetration of Echinocandin Antifungals at the Site of Infection in an Intra-abdominal Abscess Model. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2017, 61, e01009-17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Abuhelwa, A.Y.; Foster, D.J.R.; Mudge, S.; Hayes, D.; Upton, R.N. Population Pharmacokinetic Modeling of Itraconazole and Hydroxyitraconazole for Oral SUBA-Itraconazole and Sporanox Capsule Formulations in Healthy Subjects in Fed and Fasted States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2015, 59, 5681–5696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gupta, A.K.; Surprenant, M.S.; Kempers, S.E.; Pariser, D.M.; Rensfeldt, K.; Tavakkol, A. Efficacy and safety of topical terbinafine 10% solution (MOB-015) in the treatment of mild to moderate distal subungual onychomycosis: A randomized, multicenter, double-blind, vehicle-controlled phase 3 study. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2021, 85, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, A.; Donadu, M.G.; Usai, D.; Dore, S.; Boscia, F.; Zanetti, S. In Vitro Antimicrobial Activity of a New Ophthalmic Solution Containing Hexamidine Diisethionate 0.05% (Keratosept). Cornea 2020, 39, 1415–1418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinna, A.; Donadu, M.G.; Usai, D.; Dore, S.; D’Amico-Ricci, G.; Boscia, F.; Zanetti, S. In vitro antimicrobial activity of a new ophthalmic solution containing povidone-iodine 0.6% (IODIM (R)). Acta Ophthalmol. 2020, 98, E178–E180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santangelo, R.; Paderu, P.; Delmas, G.; Chen, Z.W.; Mannino, R.; Zarif, L.; Perlin, D.S. Efficacy of oral cochleate-amphotericin B in a mouse model of systemic candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2000, 44, 2356–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Gasser, G.; Metzler-Nolte, N. The potential of organometallic complexes in medicinal chemistry. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2012, 16, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kljun, J.; Scott, A.J.; Rizner, T.L.; Keiser, J.; Turel, I. Synthesis and Biological Evaluation of Organoruthenium Complexes with Azole Antifungal Agents. First Crystal Structure of a Tioconazole Metal Complex. Organometallics 2014, 33, 1594–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevanović, N.L.; Aleksic, I.; Kljun, J.; Bogojevic, S.S.; Veselinovic, A.; Nikodinovic-Runic, J.; Turel, I.; Djuran, M.I.; Glišić, B.Đ. Copper(II) and Zinc(II) Complexes with the Clinically Used Fluconazole: Comparison of Antifungal Activity and Therapeutic Potential. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrejević, T.P.; Aleksic, I.; Počkaj, M.; Kljun, J.; Milivojevic, D.; Stevanović, N.L.; Nikodinovic-Runic, J.; Turel, I.; Djuran, M.I.; Glišić, B.Đ. Tailoring copper(II) complexes with pyridine-4,5-dicarboxylate esters for anti-Candida activity. Dalton Trans. 2021, 50, 2627–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savic, N.D.; Vojnovic, S.; Glisic, B.Ð.; Crochet, A.; Pavic, A.; Janjic, G.V.; Pekmezovic, M.; Opsenica, I.M.; Fromm, K.M.; Nikodinovic-Runic, J.; et al. Mononuclear silver(I) complexes with 1,7-phenanthroline as potent inhibitors of Candida growth. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 156, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Polvi, E.J.; Averette, A.F.; Lee, S.C.; Kim, T.; Bahn, Y.; Veri, A.O.; Robbins, N.; Heitman, J.; Cowen, L.E. Metal Chelation as a Powerful Strategy to Probe Cellular Circuitry Governing Fungal Drug Resistance and Morphogenesis. PLoS Genet. 2016, 12, e1006350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, Y.; Betts, H.; Keller, S.; Cariou, K.; Gasser, G. Recent developments of metal-based compounds against fungal pathogens. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 10346–10402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishikawa, H.; Fukuda, Y.; Mitsuyama, J.; Tashiro, M.; Tanaka, A.; Takazono, T.; Saijo, T.; Yamamoto, K.; Nakamura, S.; Imamura, Y.; et al. In vitro and in vivo antifungal activities of T-2307, a novel arylamidine, against Cryptococcus gattii: An emerging fungal pathogen. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 1709–1713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sun, N.; Wen, J.; Lu, G.; Hong, Z.; Fan, G.; Wu, Y.; Sheng, C.; Zhang, W. An ultra-fast LC method for the determination of iodiconazole in microdialysis samples and its application in the calibration of laboratory-made linear probes. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2010, 51, 248–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ravu, R.R.; Jacob, M.R.; Khan, S.I.; Wang, M.; Cao, L.; Agarwal, A.K.; Clark, A.M.; Li, X. Synthesis and Antifungal Activity Evaluation of Phloeodictine Analogues. J. Nat. Prod. 2021, 84, 2129–2137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, J.W.; Lee, K.; Kim, S.; Lee, Y.R.; Kim, H.J.; Seo, K.J.; Lee, M.H.; Yeon, S.K.; Jang, B.K.; Park, S.J.; et al. Optimization and Evaluation of Novel Antifungal Agents for the Treatment of Fungal Infection. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 15912–15935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kato, I.; Ukai, Y.; Kondo, N.; Nozu, K.; Kimura, C.; Hashimoto, K.; Mizusawa, E.; Maki, H.; Naito, A.; Kawai, M. Identification of Thiazoyl Guanidine Derivatives as Novel Antifungal Agents Inhibiting Ergosterol Biosynthesis for Treatment of Invasive Fungal Infections. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 10482–10496. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Tu, J.; Han, G.Y.; Liu, N.; Sheng, C.Q. Novel Carboline Fungal Histone Deacetylase (HDAC) Inhibitors for Combinational Treatment of Azole-Resistant Candidiasis. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 1116–1126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krishnamurthy, S.; Plaine, A.; Albert, J.; Prasad, T.; Prasad, R.; Ernst, J.F. Dosage-dependent functions of fatty acid desaturase Ole1p in growth and morphogenesis of Candida albicans. Microbiology-Sgm 2004, 150, 1991–2003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DeJarnette, C.; Meyer, C.J.; Jenner, A.R.; Butts, A.; Peters, T.; Cheramie, M.N.; Phelps, G.A.; Vita, N.A.; Loudon-Hossler, V.C.; Lee, R.E.; et al. Identification of Inhibitors of Fungal Fatty Acid Biosynthesis. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 3210–3223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowes, D.J.; Miao, J.; Al-Waqfi, R.A.; Avad, K.A.; Hevener, K.E.; Peters, B.M. Identification of Dual-Target Compounds with Anti-fungal and Anti-NLRP3 Inflammasome Activity. ACS Infect. Dis. 2021, 7, 2522–2535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pue, N.; Guddat, L.W. Acetohydroxyacid Synthase: A Target for Antimicrobial Drug Discovery. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2014, 20, 740–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camilli, G.; Griffiths, J.S.; Ho, J.; Richardson, J.P.; Naglik, J.R. Some like it hot: Candida activation of inflammasomes. PLoS Pathog. 2020, 16, e1008975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, V.; Feio, M.J.; Bastos, M. Role of lipids in the interaction of antimicrobial peptides with membranes. Prog. Lipid Res. 2012, 51, 149–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, B.; Augusto, M.T.; Felício, M.R.; Hollmann, A.; Franco, O.L.; Gonçalves, S.; Santos, N.C. Designing improved active peptides for therapeutic approaches against infectious diseases. Biotechnol. Adv. 2018, 36, 415–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Struyfs, C.; Cammue, B.P.A.; Thevissen, K. Membrane-Interacting Antifungal Peptides. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2021, 9, 649875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donadu, M.G.; Peralta-Ruiz, Y.; Usai, D.; Maggio, F.; Molina-Hernandez, J.B.; Rizzo, D.; Bussu, F.; Rubino, S.; Zanetti, S.; Paparella, A. Colombian Essential Oil of Ruta graveolens against Nosocomial Antifungal Resistant Candida Strains. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donadu, M.G.; Usai, D.; Marchetti, M.; Usai, M.; Mazzarello, V.; Molicotti, P.; Montesu, M.A.; Delogu, G.; Zanetti, S. Antifungal activity of oils macerates of North Sardinia plants against Candida species isolated from clinical patients with candidiasis. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 34, 3280–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bua, A.; Usai, D.; Donadu, M.G.; Delgado Ospina, J.; Paparella, A.; Chaves-Lopez, C.; Serio, A.; Rossi, C.; Zanetti, S.; Molicotti, P. Antimicrobial activity of Austroeupatorium inulaefolium (HBK) against intracellular and extracellular organisms. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 2869–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolan, K.; Montgomery, S.; Buchheit, B.; DiDone, L.; Wellingtone, M.; Krysan, D.J. Antifungal Activity of Tamoxifen: In Vitro and In Vivo Activities and Mechanistic Characterization. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009, 53, 3337–3346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Koselny, K.; Green, J.; DiDone, L.; Halterman, J.P.; Fothergill, A.W.; Wiederhold, N.P.; Patterson, T.F.; Cushion, M.T.; Rappelye, C.; Wellington, M.; et al. The Celecoxib Derivative AR-12 Has Broad-Spectrum Antifungal Activity In Vitro and Improves the Activity of Fluconazole in a Murine Model of Cryptococcosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2016, 60, 7115–7127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Posch, W.; Wilflingseder, D.; Lass-Florl, C. Immunotherapy as an Antifungal Strategy in Immune Compromised Hosts. Curr. Clin. Microbiol. Rep. 2020, 7, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rachini, A.; Pietrella, D.; Lupo, P.; Torosantucci, A.; Chiani, P.; Bromuro, C.; Proietti, C.; Bistoni, F.; Cassone, A.; Vecchiarelli, A. An anti-beta-glucan monoclonal antibody inhibits growth and capsule formation of Cryptococcus neofonnans in vitro and exerts therapeutic, anticryptococcal activity in vivo. Infect. Immun. 2007, 75, 5085–5094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mambro, T.D.; Vanzolini, T.; Bruscolini, P.; Perez-Gaviro, S.; Marra, E.; Roscilli, G.; Bianchi, M.; Fraternale, A.; Schiavano, G.F.; Canonico, B.; et al. A new humanized antibody is effective against pathogenic fungi in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 19500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nosanchuk, J.D.; Dadachova, E. Radioimmunotherapy of fungal diseases: The therapeutic potential of cytocidal radiation delivered by antibody targeting fungal cell surface antigens. Front. Microbiol. 2012, 3, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heung, L.J.; Luberto, C.; Del Poeta, M. Role of sphingolipids in microbial pathogenesis. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 28–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Levery, S.B.; Momany, M.; Lindsey, R.; Toledo, M.S.; Shayman, J.A.; Fuller, M.; Brooks, K.; Doong, R.L.; Straus, A.H.; Takahashi, H.K. Disruption of the glucosylceramide biosynthetic pathway in Aspergillus nidulans and Aspergillus fumigatus by inhibitors of UDP-Glc: Ceramide glucosyltransferase strongly affects spore germination, cell cycle, and hyphal growth (vol 525, pg 59, 2002). Febs Lett. 2002, 526, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rittershaus, P.C.; Kechichian, T.B.; Allegood, J.C.; Merrill, A.H., Jr.; Hennig, M.; Luberto, C.; Del Poeta, M. Glucosylceramide synthase is an essential regulator of pathogenicity of Cryptococcus neoformans. J. Clin. Investig. 2006, 116, 1651–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Mandala, S.M.; Thornton, R.A.; Frommer, B.R.; Curotto, J.E.; Rozdilsky, W.; Kurtz, M.B.; Giacobbe, R.A.; Bills, G.F.; Cabello, M.A.; Martín, I. The Discovery of Australifungin, a Novel Inhibitor of Sphinganine N-Acyltransferase from Sporormiella-Australis—Producing Organism, Fermentation, Isolation, and Biological-Activity. J. Antibiot. 1995, 48, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Achenbach, H.; Mühlenfeld, A.; Fauth, U.; Zähner, H. The galbonolides. Novel, powerful antifungal macrolides from Streptomyces galbus ssp. eurythermus. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1988, 544, 128–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mora, V.; Rellaa, A.; Farnouda, A.M.; Singha, A.; Munshia, M.; Bryana, A.; Naseema, S.; Konopkaa, J.B.; Ojimab, I.; Bullesbachc, E.; et al. Identification of a New Class of Antifungals Targeting the Synthesis of Fungal Sphingolipids. Mbio 2015, 6, e00647-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kryštůfek, R.; Šácha, P.; Starková, J.; Brynda, J.; Hradilek, M.; Tloušt’ová, E.; Grzymska, J.; Rut, W.; Boucher, M.J.; Drąg, M.; et al. Re-emerging Aspartic Protease Targets: Examining Cryptococcus neoformans Major Aspartyl Peptidase 1 as a Target for Antifungal Drug Discovery. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 6706–6719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Agent | Spectrum of Activity | Route of Administration | Company/Sponsor | Current Status | Clinical Trial Registration Number |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T-2307 | Broad spectrum | IV | Toyama Chemical Ltd. | Phase I completed (as stated in [57], but no actual data available in the literature) | Not available |

| Fosmanogepix | Candida spp. (except C. krusei) and Aspergillus spp. | PO/IV | Amplyx Pharmaceuticals | Phase II recruiting | NCT04240886 |

| Nikkomycin Z | Candida spp. and Aspergillus spp. | PO | University of Arizona | Phase I completed; however lack of funding and volunteers caused the termination of phase II studies | NCT00834184 |

| Olorofim | Aspergillus spp. and uncommon molds | PO/IV | F2G Ltd. | Phase II Phase III planned (not yet recruiting) | NCT03583164 NCT05101187 |

| VL-2397 | Aspergillus spp. and some Candida spp. | IV | Vical Biotechnology | No current development plans (phase II trial terminated early, because of a business decision) | NCT03327727 |

| Aureobasidin A | Board spectrum and proliferative tachyzoite form of toxoplasma (antiprotozoal) | PO/IV | Takara Bio Group | Preclinical | Not available |

| MGCD290 | Candida spp. and Aspergillus spp. | PO | MethylGene, Inc. | Further development suspended after phase II clinical trial | NCT01497223 |

| VT-1129 | Candida spp. and Cryptococus spp. | PO | Viamet Pharmaceuticals Inc. | Preclinical | Not available |

| VT-1161 | Candida spp., coccidioides spp., and Rhizopus spp. | PO | Mycovia Pharmaceuticals | Phase III completed | NCT03561701 |

| VT-1598 | Candida spp., Aspergillus spp., and Cryptococus spp. | PO | Mycovia Pharmaceuticals Clinical trial sponsored by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) | Phase I | NCT04208321 |

| Ibrexafungerp | Candida spp. and Aspergillus spp. | PO/IV | Scynexis, Inc. | Phase III | NCT03059992 |

| Isavuconazole | Broad spectrum | PO (Isavuconazonium sulfate PO/IV) | Basilea and Astellas Clinical trials sponsored by Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center and M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, respectively. | Phase II trials completed FDA approved in 2015 for the treatment of aspergillosis and invasive mucormycosis | NCT03149055 NCT03019939 |

| Albaconazole | Broad spectrum | PO | Palau Pharma Clinical trial sponsored by GSK | Phase II completed | NCT00730405 |

| Iodiconazole | Broad spectrum | Topical | Second Military Medical University and Anhui Jiren Pharmaceutical | Phase III (as stated in [58], but no actual data available in the literature) | Not available |

| BSG005 | Broad spectrum | IV | Biosergen AS | Phase I | NCT04921254 |

| Rezafungin | Candida spp., Aspergillus spp., and Pneumocystis jirovecii | IV | Cidara Therapeutics, Inc. | Phase III | NCT03667690 NCT04368559 |

| SUBA-itraconazole | Broad spectrum | PO | Mayne Pharma Ltd. | Phase II FDA approved in 2018 for the treatment of aspergillosis, histoplasmosis, and blastomycosis in patients contraindicated to amphotericin B | NCT03572049 |

| Topical terbinafine solution | Onychomycosis | Topical 10% solution | Moberg Pharma | Phase III | NCT02859519 |

| Amphotericin B cochleate | Broad spectrum | PO | Matinas BioPharma | Phase II | NCT02629419 |

| Structural Type | General Structure * | Target | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phloeodictine analogues |  | Fungal ergosterol biosynthesis | [59] |

| Biphenylethylaminoacetamides |  | Fungal cell wall integrity | [60] |

| Thiazoyl guanidine derivatives |  | Fungal ergosterol biosynthesis | [61] |

| Carboline HDAC inhibitors |  | Fungal histone deacetylase | [62] |

| Acyl hydrazides |  | Fungal fatty acid biosynthesis | [64] |

| Thiobenzoate scaffolds |  | Dual target: fungal acetohydroxyacid synthase and NLRP3 inflammasome | [65] |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bouz, G.; Doležal, M. Advances in Antifungal Drug Development: An Up-To-Date Mini Review. Pharmaceuticals 2021, 14, 1312. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ph14121312

Bouz G, Doležal M. Advances in Antifungal Drug Development: An Up-To-Date Mini Review. Pharmaceuticals. 2021; 14(12):1312. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ph14121312

Chicago/Turabian StyleBouz, Ghada, and Martin Doležal. 2021. "Advances in Antifungal Drug Development: An Up-To-Date Mini Review" Pharmaceuticals 14, no. 12: 1312. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ph14121312