1. Introduction: An Emerging Field of Study

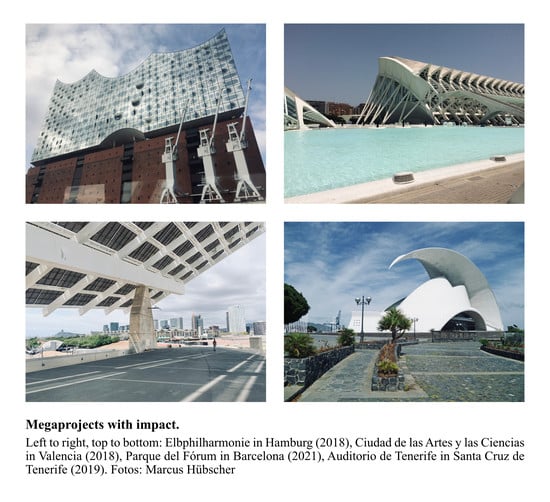

Large-scale urban projects are an essential element in the neoliberal city. Megaprojects worldwide document this, reporting from the Guggenheim Museum and the “Cinderella transformation” of Bilbao [

1], to the business-friendly Canary Wharf, London [

2] and the export hit “Barcelona Model” [

3].

The rising number of such projects goes back to two parallel and overlapping trends. First, the economic transition toward post-industrial societies turns formerly industrially used areas into brownfield sites, which, often located in strategically important districts, cities need to cope with [

4]. Second, the advancing neoliberalization has sharpened competition between cities on a global scale [

5]. In this context, urban megaprojects are regarded as welcome opportunities to give these cities a facelift, establish a marketable image, and boost the urban economy [

6]. By definition, these projects seek to renew, regenerate, or upgrade the area where they are built. Simultaneously, they often foster touristification, segregation, or gentrification that, once unleashed, are difficult to tame.

Given the obvious relevance of this topic in cities worldwide, it is not surprising that research on large-scale urban developments is also skyrocketing. The number of scientific publications (search terms were “megaprojects” AND “large-scale urban development projects” AND “brownfield”) has octuplicated from only 76 in 2010 to 610 in 2020 on the Web of Science [

7]. The expanding scientific interest has fueled various key works in the literature from different backgrounds, for example, management [

8], planning [

9], architecture [

10], or urbanism [

6]. Although adjacent fields of research such as gentrification or urban tourism are much more established, the intersection between these two fields and megaprojects is relatively new. This is the gap that this paper shall help to fill by systemizing the already existing knowledge, which expands at a strong pace. To date, there has been no systematic review of studies about the relationship between large urban projects, gentrification, and tourism, which is why I argue that an overview contributes to a better understanding.

The aim of this paper is not to discuss the relationship between megaprojects, tourism, and gentrification in depth. Rather, it is to systemize contributions that have already been made and serve as a summarizing guide through the ongoing discussion that takes place in these included studies. I will structure this descriptive review as follows. Section two presents the steps taken during the literature review. Section three discusses the results and contains both a bibliometric and a content-related analysis. It is firstly revealing to obtain insights into the “when, where and how” of these studies. I will particularly document the spatial dimensions in the discussions. Secondly, with regard to contents, the objective is to identify the most relevant topics, concepts and frames presented and explore the existing lines of discussion. Section four draws a conclusion based on these findings.

2. Materials and Methods: Conducting the Review

Conducting a systematic literature review consists of several steps. I strongly relied on the suggestions made by Green et al. [

11], Rowley and Slack [

12], and particularly Xiao and Watson [

13], who provided guidance on reviews in planning research. Apart from that, I also followed the PRISMA 2020 guidelines, which are a set of requirements to facilitate systematic reviews [

14]. On that basis, I understand systematic reviews as a procedure to “collate and synthesize findings of studies” [

14] in order to “distill the existing literature in a subject field” [

12].

The first steps in a review are to define the problem and develop a review protocol [

13]. Based on my research question presented in section one, this paper aims to explore the relationship between megaprojects, gentrification, and tourism. Hence, these terms are the keywords that I used in search engines. My understanding of these concepts is based on Diaz Orueta and Fainstein [

6], Flyvbjerg [

8], and Swyngedouw [

15], who made important contributions to these phenomena. In this preliminary research, I also found that terms are not used consistently—particularly in the case of megaprojects. There are other terms applied, not always in a synonymous way though, such as “large-scale urban development projects” [

15]. There might even be cases where the authors describe megaprojects without clearly labelling them as such, as is the case in “brownfield” redevelopment projects. I decided to also include these two keywords in my search and looked for scientific contributions that contain “gentrification”, “tourism”, and “megaprojects” (or one of the above-mentioned synonyms) by connecting these terms with “AND” operators.

With regard to conducting the review, the electronic databases must be selected. According to Green et al. [

11], it is essential to combine several search engines since none of them contain all of the relevant documents. In this literature review, I combined Google Scholar, Web of Science, ProQuest, SocIndex, and two university library databases that I had access to. In case there were many results, I selected the first 100 hits, sorted by relevance.

As

Figure 1 shows, I started the review with 797 hits, which I found in August 2021. All of them were imported to a literature management program (Endnote, version X9.3.3), which detected 192 duplicates. In the following screening process, I applied a two-stage protocol [

13]. For the remaining 605 entries, I scanned the title, abstract, and keywords, and excluded records that were not relevant to my research question. In case I was unsure, I kept the text in the review, based on Xiao’s and Watson’s [

13] recommendation.

The remaining 308 records were screened for retrieval and eligibility, based on their full texts. Exclusion criteria were, for example, non-English language and a lack of accessibility or quality (

Figure 1). Texts that did not undergo peer-reviewed procedures were also eliminated. I excluded studies where I participated, to reduce personal bias, but I added them when putting the results into a broader context.

Apart from that, rules for inclusion were applied. I only included those texts in my review that had obvious links to the three main concepts (megaprojects, gentrification, tourism). With 66 final texts, I perceived that the number of studies included was already high, which is why a back-and-forth search was not added.

This procedure implicates several limitations. Based on the strict selection of the search terms, the review does not include studies that might have the same research interest but uses different wording. Moreover, only open access contributions and studies available via the university’s library could be accessed, which reduced the number of possible records by 22%. A further point of discussion is the decision to only include peer-reviewed and high-quality contributions. That means that most of the conference proceedings and grey literature were excluded. Hence, the review presented here cannot claim to discover the breadth of studies but rather represents a specific section. In this respect, a literature review contains the subjective decisions made by the researcher and the results will differ if any of the abovementioned factors are altered. However, revealing the chosen procedure increases the replicability of this review and this is what I regard as good scientific practice.

The final step was to analyze the documents included and report the findings [

13]. Here, I applied techniques of a qualitative content analysis based on Mayring [

16]. To develop the category system, I applied two approaches (deductive and inductive). I set up categories that derive from the research question and the basic literature that I used to determine the keywords (deductive) [

17]. There were several framework codes that were set up before the review was compiled, for example, the place of the case studies, methods applied, objectives, project descriptions, etc. [

11]. I started analyzing the documents and completed the category system based on the material (inductive) [

17]. These codes were rather content-related. After the first ten papers, the code system seemed saturated; it did not grow extensively from that point on. Consequently, I checked these first papers again, which should be performed after having at least 10% of the material coded [

18]. Apart from that, I also worked with memos, which meant taking notes during the entire process, and later used these thoughts for the analysis [

12]. I used the codes in order to define overarching themes among the documents and also to draw comparisons between the text segments [

19]. In this process, I deducted general descriptions, also known as abstraction “through generating categories” [

20].

3. Results

Referring to the findings, this paper contains both a quantitative and qualitative approach. Firstly, aspects such as the publication frameworks (year of publication, medium, places of the case studies, etc.) were assessed using descriptive statistics (

Section 3.1). Secondly, I gathered the studies’ concepts and places (

Section 3.2), on the one hand, and overarching topics [

13], lines of discussion, as well as differences and similarities between the studies [

11], on the other hand (

Section 3.3).

3.1. Bibliographic Analysis

The bibliometric analysis explores the documents included from a quantitative point of view [

21]. I do so in a descriptive way and put the focus on the types of publications, the geographical place of the case studies, and the topics named in abstracts and keywords.

3.1.1. Publications

Research on megaproject, gentrification, and tourism is a dynamic field, with a considerable increase in contributions during the last few years. This growth set in after 2010. Between 2011 and 2021, 85% of all the studies included were published. Indeed, similar evolutions have been observed in other literature reviews, for example, one about gentrification research [

22]. This might be linked to the general increase in contributions in the field of gentrification. This growth might be traced back to the impacts of 2008′s financial crisis. Indeed, researchers have argued that large-scale urban projects were used in the crisis’ aftermath to promote growth [

23,

24]. A similar logic is observed with regard to tourism, for example, in Spanish cities [

25]. This proves the topicality of these phenomena, particularly against the background of the current COVID-19 crisis. During the last two decades, 2019 stands out most: 21% of all the studies were published in this year [

26]. The search engines consulted did not find contributions published prior to 2002. Of course, this does not necessarily mean that the phenomenon did not occur until then. Rather, it indicates that the keywords proposed in this review did not address older studies, which shows another limitation of my approach.

Comparing the authorships of the texts revealed a quite balanced research landscape, even when compared to other reviews on neighboring topics [

22]. There was only one author (Doucet) who appeared three times in the review [

27,

28,

29]. Five authors had two records. On the contrary, a vast majority—more than 80%—was written by authors with only one study.

With regard to the type of publication, 83% of all the records are papers in scientific journals, only 17% are book chapters (

Figure 2). About one-third of these papers (64%) were published in journals that only occur once in the review. Again, this underlines the diversity of the field, as there are 40 different journals in total. Furthermore, journals possess a range of impact factors. Although about one-fifth of the journals are not listed on the Web of Science, there is a large share of contributions with lower factors (35% under 2.0), and a considerable share with a high factor (28% over 4).

I also reflected on which of the search engines provided the best results.

Figure 3 reveals that Google Scholar, ProQuest, and University Library #1 found large shares of the total number of records. Moreover, the databases perform differently when it comes to efficiency, i.e., the share of records included in the review. While Google Scholar, University Library #1, and the Web of Science even slightly increased their share in the final review, ProQuest, University Library #2, and SocIndex decreased. In total, the Web of Science had the most efficient performance of all, as it had a hit rate of 16%. Google Scholar’s hit rate was only 8%; however, it found the largest number of studies, which still contributes significantly to this review. Norris et al. drew the same conclusion in their comparative analysis of different search engines, namely that Google Scholar performs the best [

30]. However, other authors [

13] and

Figure 3 show that using a variety of search tools contributes significantly to finding a diverse set of relevant documents.

3.1.2. Places and Projects

This paragraph looks at the geographical scale of studies included in the review. There are two dimensions to that. I will first investigate the cities and projects that are cited within the documents of this review. The aim here is to identify the most visible megaprojects worldwide and their spatial distribution. Secondly, I will change the perspective and focus on cities and projects that serve as case studies in the literature.

Figure 4 reveals the visibility of large-scale urban projects within the academic discourse. More than one-quarter of all the projects cited (26%) are located in Mediterranean countries, where tourism typically plays an essential role in urban development. The maps also show that countries of the so-called “global north” account for two-thirds of all the projects named. Although Asian countries (14%) and the Gulf region (11%) have important shares, other areas, such as South America (2%) or Sub-Saharan Africa (1%), rarely appear.

The countries with most citations are Spain, the U.S., and the United Kingdom. In particular, the case of Spain speaks for itself. As a relatively small nation with only 14% of the population of the U.S., it is the country that reaches the highest number of project references within this review. This also goes for the United Arab Emirates, a country with barely 10 million inhabitants, but a considerable number of citations based on Abu Dhabi’s and Dubai’s megaprojects.

This is also reflected in the statistics on the cities cited (

Table 1)—with London, Bilbao, and Barcelona being the top three cities discussed, all of which are located in Europe. The most-referenced projects are Bilbao’s Guggenheim Museum, followed by Canary Wharf, London.

Apart from the cited cities, I also explored which cities are analyzed by means of case studies within the review. In total, 78 projects are discussed. Almost half of this group (49%) is studied at least two times, the rest are studied only once. Again, the statistics reveal the strong role of the UK, the U.S., and Spain (

Table 2). Although it was the city most cited (

Table 1), Bilbao does not dominate the ranking (

Table 2). In contrast, it is Rotterdam and the Netherlands that reach the top positions in both tables, but neither of them belong in the top 10 list of the cited projects or cities. Here, the dominance of case studies in the “global north” is even more obvious compared to the references made: 70% of the case studies take place there.

Figure 5 insinuates a relationship between the number of case studies per country included in the literature review, on the one hand, and the number of cited reference projects, on the other hand. This serves as a control proxy for the representativeness of the case studies selected. For example, there is no country with many citations that did not also appear in a case study within the review. The countries located above the trend line have a case study surplus compared to those countries below the line. This means that the U.S. or the United Arab Emirates (UAE), for example, are cited quite often, although there are not as many case studies in these countries compared to others. This suggests that projects such as Burj Khalifa (Dubai) or Atlantic Yards (New York) have high visibility within the academic discussion. Contrarily, megaprojects in The Netherlands, Germany, and the UK, appear in a relatively high number of case studies but have less visibility within the academic discussion.

Figure 5 also proves the polarized setting of the case studies. Spain, the UK, and the U.S. are ahead of all other countries, on the one hand, while there is a large group of countries with only one or two case studies, on the other hand. Only the UAE assumes a medial position.

3.1.3. Keywords and Abstracts

Exploring keywords and abstracts quantitatively is a first step to approach the contents of the records included. Both types of data reveal which key terms and concepts are linked to the texts—from the authors’ perspectives. In this paper, I assess these aspects in order to extract categories for the qualitative analysis (inductive) and gather first impressions of relevant research topics.

With regard to keywords, the term “urban” is used most. Out of the 699 keywords included, it appeared 65 times, and almost two-thirds of all the records use it (

Table 3). I explain this high frequency with the multiple meanings of the term. “Urban” is understood as the spatial scale, where the researched phenomena take place. Apart from that, it also entails a conceptual meaning, and is combined as an adjective with other terms, such as “renewal” or “project”.

Interestingly, the second most important keyword is “planning” (used by 39% of the records), which indicates the importance of this field as a research perspective. The first place-related keyword is “waterfront” (rank 7), which indicates the relevance of conversion areas near blue infrastructures in one-fifth of the texts included.

Another striking fact is that the keywords I used in search engines to find the relevant literature (see

Section 2) play minor roles in

Table 3. The term “brownfield” only occurs in 4% of the documents and tourism in 8%. Out of all the keywords, “gentrification” reaches the highest position (rank 10). This observation insinuates that gentrification, tourism, and megaprojects might indeed be the conceptual framework of many studies, while other specific aspects are researched in detail.

Regarding the keywords, I also used the VOSviewer to analyze the appearances (

Figure 6). VOSviewer is a program designed to visualize bibliometric items [

31]. The volume of the labels is determined by the weight of each item. Moreover, the algorithm clusters the items according to their co-occurrence. This means that closeness represents stronger relatedness [

32], but the lines also represent links between the keywords.

For this term map, 316 keywords were used in total. Contrary to

Table 3, the keywords were not split up, which means that for example “urban planning” was not divided into “urban” and “planning”. The minimum number of appearances was three, which means that 17 keywords met the threshold. The clusters do not match perfectly from a thematic perspective, as they are generated automatically. However, I used this map as a complementary tool to enrich the analysis. In the top map in

Figure 6, three thematic clusters are identified. Cluster one (red) mainly contains study areas such as social sciences or urban studies, showing the background of the documents used in the review. Cluster two (black) is a large, but rather disperse group that contains places (cities), and also processes such as urban renewal and urban planning. Cluster three (blue) only includes three concepts, namely, megaprojects, gentrification, and urban regeneration, representing those studies that analyze projects in the context of their city’s development.

The second map displayed at the bottom in

Figure 6 contains the same keywords but they are referenced by their year of publication. With only 66 documents included, the data set is relatively small and representativity must be questioned. However, this map indicates a shift in the usage of terms. The older keywords (around 2010) mainly contain disciplines (urban studies, social sciences), while the younger keywords (around 2014) focus on objects or processes (megaprojects, cities, urban planning). This trend might be confirmed for larger samples in future research.

Figure 7 visualizes the quantitative analysis of the abstracts and contains words that occurred at least ten times. These words are classified into the following five groups: stakeholder, process, scale, concept, and project. Compared to the VOSviewer map above, I find

Figure 7 less conceptual, but easier to interpret. Hence, I used these umbrella terms to begin constructing the category system, on which the further qualitative analysis was based (see

Section 3.3.).

3.2. Concepts

Apart from the more quantitative aspects described in

Section 3.1, I wanted to cover the conceptual aspects of this review, referring to methods, research objectives, the theoretical frame, and the location of the projects cited within the cities.

3.2.1. Methods

I will firstly illustrate which concepts the included studies have. There is a clear majority of case studies (

Figure 8), which account for almost 82% of the texts analyzed. Contrary to that, only about 10% are mere theoretical contributions. This indicates how the discussion on megaprojects, gentrification, and tourism has a strong project-related approach. I traced this back to the emerging character of this field of research (

Section 3.1.1). It seems logical that, in an initial phase of the discussion, researchers explore the phenomena by means of case studies, while the theoretic background is yet to evolve. However, 35% of all the case studies apply a comparative approach including projects in at least two different cities, which seems to be the first step in generating conceptual ideas.

Figure 8 also shows that half of the case studies rely on qualitative methods. Only 11% of the case studies have a quantitative approach. About 26% use document analyses, but only 6% apply it as a single method, the rest combine it with other instruments. In fact, conducting both document analysis and interviews is the most common approach to the case studies—almost one-fifth choose this combination. About 28% of the studies do not specify nor discuss their methods.

3.2.2. Objectives

Scanning through the research concepts of the studies selected, I identified the following three groups of objectives that are typically pursued: descriptions, evaluations, and reflections. These objectives overlap in some studies, in others, they occur separately.

Firstly, as case studies represent the majority of contributions in the review, it is not surprising that one main objective is to describe the projects. However, emphasis varies strongly. Many studies “describe and analyze the transformation” [

33] provoked by large-scale projects. Further aspects range from planning processes [

34], stakeholders [

27], and motivations [

35], to the design of megaprojects [

36].

Secondly, there is an important body of literature that aims to evaluate the impacts of these projects. By placing the megaprojects into their cities’ contexts, the research focus is put, for example, on (social and environmental) justice and public protests. In this respect, some researchers explicitly explore the relationship between “urban public policy and gentrification” [

37]. Furthermore, the expected positive impacts are also researched. The so-called “trickle-down effect” is a narrative that many megaprojects provide, but it is also one that is questioned by scholars [

38].

Thirdly, studies critically reflect not only the projects but also the frames and conditions, where such large-scale developments emerge. Here, megaprojects are described as “local productions of the global” [

39], referring to globalized trends such as the entrepreneurial turn [

40,

41], the neoliberal urban hegemony [

42], inter-city competition [

43], or financialization [

3].

3.2.3. Theoretical Frame

Analyzing the theoretical frames used by the studies is another way to approach the review. There is a large variety of theories used and not all the studies clearly indicate the frame they have applied.

Table 4 summarizes the four most important frames used.

Firstly, the theoretical umbrella concept with the most contributions is, by far, neoliberalization. Representatives such as Moulaert (55%), Harvey (55%), or Swyngedouw (59%) are cited among more than half of the documents each. Within this frame, I identified the largest variety of aspects. The linkage between megaprojects, tourism, and gentrification is associated with urban entrepreneurialism [

27] and privatization [

44], the global competition between cities [

45], or forms of governance [

23].

Secondly, a smaller, but still important frame is culture and image, with main authors such as Sharon Zukin and Richard Florida. Both are cited by about one-quarter of the documents. The studies that refer to this frame interpret large-scale projects as a means to re-shape or “re-imagine” [

36] the city, or highlight the essential role of culture in urban development [

40].

Urban justice is a third frame used by the studies, which explores “questions that pertain to the geographic scale at which justice may be produced, the nature of economic versus other forms of injustice, the universality of the concept, and the importance of process versus outcomes” [

34]. With authors such as Peter Marcuse (16%) and Edward Soja (11%), these concepts are rather specific and not applied as often compared to other concepts. However, this frame contains some strong and visible aspects such as environmental justice [

46] or gentrification as a question of social and spatial justice [

47].

Fourthly, another perspective deals with planning and policy from a very practical point of view. Here, large-scale projects are integrated within urban programs to stop urban decline [

48], initiate brownfield regeneration [

49], or “make cities competitive with suburbs” [

50].

Another part of understanding the theoretical frame is to analyze the key terms used to describe the projects. I began this literature review by determining “megaprojects”, “large-scale urban development projects”, and “brownfield” as key terms and used them to search for literature in different databases. It is revealing to see how the final 66 documents actually use these terms.

Figure 9 reveals that a minority of records applies only one of the concepts. On the contrary, half of the texts use both “megaproject” and “large-scale urban development project” synonymously. About 12% even add “brownfield” as a third description. Comparing the three terms with each other, “brownfield” is the one that is less used. Apart from that, only 14 out of the 66 studies (21%) explicitly offer a definition of what they understand under the concepts applied.

3.2.4. Projects’ Locations within Cities

I also tagged each case study with regard to their city-specific location. Almost half of all the location tags belong to the category “waterfront” (44%), which indicates the large share of megaprojects related to blue infrastructures. About 31% of the tags are in the category “brownfield”. This is quite surprising because it proves the relevance of such conversion projects for the research interest presented in this paper, on the one hand. Conversely,

Figure 9 and

Table 3 clearly show how the specific term “brownfield” only plays a minor role as a keyword or concept. This means that there is a gap between the actual relevance of conversion projects and the labeling of such as brownfield sites. Apart from that, there are also other sites named, such as neighborhoods (17%), and developments on the greenfield (7%).

Comparing these findings to the literature reveals that other scholars have observed a similar development. Diaz Orueta and Fainstein [

6] even speak of a new generation of megaprojects and see in their location on waterfronts or old manufacturing areas the main elements of their definition. They add to the discussion that building these projects on derelict land increases public acceptance because, apparently, no one is displaced from there [

6]. Hence, this can be interpreted as a strategy promoted by the projects’ initiators to avoid protest [

43]. It also goes back to the ongoing economic transition toward the post-industrial city, which leaves many former industrially used places without a function [

63].

3.3. Topics and Contents

This section digs deeper into the contents discussed by the documents included in this literature review. I do so by presenting the code system, and three selected topics, namely gentrification, tourism, and planning.

Table 5 contains a selection of codes, which helps to give a first overview of the most relevant and overarching topics dealt with. The table does not show concept-related codes such as methods, projects’ descriptions, or objectives, it rather focuses on contents.

Some of the codes I had already prepared based on previous knowledge and what was to be expected based on other literature and the analysis of keywords and abstracts (project-related data, planning, justice). Additionally, many subcategories were built on the material. For example, 71% of all the studies explain the diverse motivations for the megaprojects described. This is a category that I did not expect. Next to “planning” (80%) and “justice” (79%), it is even one of the largest categories, at least considering the number of documents where they appear.

3.3.1. Gentrification

Large-scale development projects can produce gentrification in multiple ways, and this also reflects the literature analyzed. New-build gentrification is indeed one of the most common phenomena, which occurs if projects are developed on a formerly unused area [

29]. Apart from that, such developments obviously influence adjacent neighborhoods. This might occur by the intention of the project’s initiators, such as in the Valencia Plan [

40]. It can also occur unintended, if there are strong market forces, such as a “self-financing imperative” [

64] and no “careful public interference” against gentrification is proposed [

65].

In any case, projects that lack spatial and functional integration within the district will provoke a strong disparity and high price differences [

66]. Moreover, new facilities such as “shopping malls, parks, luxurious hotels, and convention centres” [

1] are part of a project to attract other social groups, such as tourists. This is also observed in green gentrification processes [

67], which territorialize “those spaces as inviting to capital, elites, and tourists” [

68]. With examples such as the Anacostia River in Washington D.C. [

34] or Medellín’s Greenbelt [

68], the discussion on green gentrification is quite young and dynamic [

69]. Green gentrification accounts for 10% of all the codes within the gentrification category and proves to be a relevant one because it exemplifies how environmental upgrading due to megaprojects does not always benefit all neighbors.

Marcuse’s concept of exclusionary displacement has been applied to this discussion, because the new housing units built in such megaprojects are rarely accessible to groups with less income [

44]. Megaprojects also produce a fear of displacement due to the expected neighborhood changes [

44]. However, the example of Rotterdam’s Kop van Zuid shows how gentrification has not spread “far beyond its boundaries” [

28]; therefore, the process is not a self-fulfilling prophecy per se.

Furthermore, the group of displaced persons is more heterogeneous than one would suppose at first glance. It is not only inhabitants evicted from their houses, but also “drivers, informal venders, and occupants” from the public spaces [

70]. In some cases, even industries are (actively) evicted to replace them with service-oriented functions. This parallelism of deindustrialization and upgrading is observed in Berlin [

71], where the city center is intended to be shifted to the east. Similar processes occur if market forces drive industrial uses from the waterfront, such as in Hong Kong [

72] or in Seoul [

73].

Apart from that, injustice is not only seen as a product of displacement. In Turkish cities, low-income groups were displaced from their (informal) settlements but were offered new apartments within the megaprojects, which appeared to be a move to integrate local inhabitants. However, they were also incorporated into “a globally articulated mortgage market which means a long-term dispossession to their labor” [

55].

In summary, the relationship between megaprojects and gentrification is complex. It is worth noting that the literature included in this review rather takes an analytical point of view, either describing or exploring these processes, rather than proposing solutions to the problem. Gentrification is not only to be regarded as a threat to a neighborhood’s sustainability, but even endangers the actual goal of the projects: It might physically regenerate a district but does not ultimately contribute to the local people’s wellbeing [

74]. If so, gentrification can become a tinderbox even for projects’ developers, because it fuels protest against the plans [

1].

3.3.2. Tourism

Tourism is studied from various points of view in the literature. While most studies confirm tourism as one key driver for megaprojects, only some explore the conflicts that the growing tourism brings about [

75].

This changes with regard to the initiators’ point of view about their megaprojects. In most cases, the predominant narrative is to attract more tourists or even position the city on the tourists’ consciousness by means of megaprojects. In this literature review, there is one exception: In the case of the Barcelona model, megaprojects were also intended to diversify the economy to be less reliant on mass tourism [

3].

The authors explain the high attractiveness of tourist functions with its profitability. Apart from luxury residences, offices, and shopping facilities, tourism (e.g., hotels) is one of the most profitable uses in megaprojects [

76], let alone the additional benefits of tourists’ spending in the city. The question is also, what role tourism plays historically in the region’s or country’s economy. In some cases, “states use tourism to define national identity through symbols, attributes, and places, and develop an important urban infrastructure to assert global recognition” [

77]. Using the global visibility of large-scale urban development projects is thus a logical consequence.

To address this visibility, there are at least two forms in which tourism forms a part of megaprojects. Firstly, there are those projects where tourism is one element among others in a mixed-use program. The variety of examples reaches from Bilbao’s Abandoibarra [

64] to Kings Waterfront in Liverpool [

49] or the Belgrade Waterfront [

57].

Secondly, in some megaprojects, tourism is the main function. Again, there are different forms of such projects, for example, the America’s Cup in 2007 in Valencia, which clearly advocates high-end tourism [

56]. Very popular examples are the spectacular museums (Guggenheim, Bilbao) [

37] or the opera houses in Oslo [

35] and Santa Cruz de Tenerife [

78]. Such “spectacular” buildings “tend to confirm one city’s cosmopolitan orientation or at least tourism-friendly identity” [

58] and reveal the connection between global image and tourism.

Apart from cultural flagship projects, tourism can be promoted in many other ways, all of them concentrated in the example of Costa del Sol, Málaga [

75]. In this case, a combination of direct large-scale investment into accommodation, the regeneration of the historic center, and a waterfront regeneration was proposed.

It is particularly the latter example, namely, waterfront projects, where tourism functions are promising, as proven in Melbourne: “the key to its success was that the development provided a north-facing, sunny exposure on the waterfront, with a brand-new panorama of the city skyline” [

33].

With regard to the impact of tourism on the concept of megaprojects and later on urban development in general, the literature included in this review assumes a rather critical position. This is basically because of the “competing demand between a place for tourism and a place for local people” [

72]. In many cases, the needs of the local people are neglected completely. This is discussed by the concept of “container tourism”, which refers to spectacular architecture that is empty of contents [

51]. In more integrative cases, there is at least some heritage conservation, which has both a value for the local identity and is also attractive for tourists [

69]. Preserving local peculiarities is an effective strategy, given the fact that from the tourists’ perspective, it can be disappointing to find just another globalized urban form in their travel destination [

69].

Overall, the literature cited in this review documents the strong belief that governance and planning based on large-scale infrastructures would foster both tourism and the image of the city itself [

40]—a key assumption under the entrepreneurial turn.

3.3.3. Planning

A third topic that I will discuss is planning, as it has obvious practical relevance. In general, I observe a critical perspective in these documents. This is because planning large-scale urban development projects poses severe problems to the existing planning framework [

24]. Apart from that, most of the observed planning processes are seen as “dark and secret” [

1], where “speed” and “urgency” [

79] reign, although these are not good planning principles.

When analyzing planning processes in megaprojects, the studies included place a strong emphasis on stakeholders. This sub-category alone accounts for 45% of all the codes included in the category “planning”. Therefore, I will describe some general aspects and later focus on public–private partnerships and the role of the state, which are both highly discussed issues.

An important step that many studies propose is to disentangle the network of stakeholders in a megaproject, as “a complex set of power relations” [

69]. There is a need to do so because these relations are regarded as complex due to the non-transparent international links of capital and power [

57]. For example, personal relations and nepotism are described as common problems [

23]. More than half of the studies also refer to the “elite” as a fuzzy and partially hidden group that tries to reach its interests by means of a megaproject [

34,

70]. It is particularly this elite that has been influenced by very visible and apparently successful transformations due to megaprojects [

1]. Contrarily, the studies do not so much focus on civic groups, neighborhood representatives, or other associations. This is probably because these groups are neither in charge nor do they contribute to the undemocratic character of projects.

Instead, the outstanding focus is placed on public–private partnerships as the prevailing model behind megaprojects [

6]. Some studies explain the motivations for this model, which serves to mobilize actors apart from governmental entities by entrepreneurial strategies [

27]. Others focus on the implications of public–private partnerships, such as Diaz Orueta and Fainstein [

6]. They criticize that the produced spaces often put profits first and urbanity second. Moreover, planning rules are modified to make them fit with logic from the private sector [

57]. This has led to “decentralized forms of governance […] while relying on state-issued exceptional rules” [

54]. In some cases, megaprojects are even used to introduce public–private partnerships to the city on a large scale as the new form of governance [

66].

Apart from that, the authors also critically investigate the role of the state. About 49% of all the codes dealing with stakeholders concentrate on public decision-makers. The state is seen as “a key articulator in speculative city development schemes” [

53]. Despite the popularity of public–private partnerships, many of the megaprojects are state-led. This is not only the case in autocratic systems [

57] but also in more democratic environments [

28]. However, it would be wrong to assume that there is just a singular stakeholder behind the term “state”. It rather must be differentiated between national, regional, and local entities [

57], or even other public bodies such as the army, port authorities, etc. [

69]. This turns the state into a highly relevant but complex aspect to study, as the public stakeholders often pursue contradicting goals [

80].

4. Conclusions

This literature review sought to systemize the existing knowledge about the intertwining fields of urban megaprojects, gentrification, and tourism. Despite the limits of the chosen procedure (e.g., limited range of keywords, focus on English-speaking discourse), I want to highlight the following three aspects that this review has shown:

Research interest: The area studied is an emerging field with a number of contributions that grow steadily. The global north and countries such as Spain, the UK, and the U.S. dominate the discussion. Journals are the type of publication where most discussions take place. Studies strongly rely on qualitative approaches or mixed methods

Format: Case studies contribute significantly to the discussion, which emphasizes the existing knowledge about how to approach megaprojects, which methods to apply and how to interpret them.

Contents: With regard to contents, topics such as planning, motivations behind projects, (social) justice, the impacts on the city, and reactions in society prevail. Half of the texts refer to authors representing concepts on neoliberalism, and about one-quarter draws on theories about culture and image. Contributions from practical perspectives represent a minority.

However, I identify the following three gaps in the literature that future research should try to fill:

Methodological gap: More than one-quarter of all the studies did not clearly explain their methods. This is problematic for the following two reasons: (1) It reduces the quality of the results because the reader cannot understand how the findings were produced. (2) It also makes it impossible to replicate research designs and thus violates the principles of good scientific practice [

81].

Transfer gap: From a more practical perspective, it is not clear at all how to bring existing knowledge about the relationship between megaprojects, gentrification, and tourism to policymakers and stakeholders in the cities. This is proven by the growing number of case studies, showing that no learning processes are taking place between the projects.

Spatial gap: From a conceptual perspective, there is a spatial gap with the global north dominating the discussion. Hence, an unreflected transfer of concepts from the global north to the south must be avoided. The large number of studies that take place in the north dealing with highly visible megaprojects easily outweighs examples from the south. Of course, new and emerging studies will take the existing concepts into consideration, but not reflecting on the local peculiarities of each phenomenon would be a mistake (see for example López-Morales [

82] for a critical discussion of north–south trajectories in gentrification research).

On that basis, I draw several conclusions that serve as guidance for further research.

Firstly, to advance the discussion, I propose a conceptual sharpening. This refers, for example, to the clear use of keywords such as megaprojects or gentrification, and also includes their transparent definitions. This is necessary to avoid softening the existing concepts. It also contributes to a clear understanding of these terms, as it is claimed in the neighboring discussion between gentrification and touristification [

83]. Regarding the high share of case studies within this discussion, more theoretical and conceptual contributions should complement the field. Apart from that, by conceptual sharpening, I also refer to providing a comprehensible description and discussion of the methods applied.

Secondly, some of the flagship projects have significantly high visibility, not only in the scientific discourse but also in practice and planning. Cities around the globe copy Barcelona or Bilbao and hope to benefit from a similar “successful” development. A critical reflection of these urban development models takes place in academia but fails to find its way to the stakeholders in planning and policy. How can this transfer of knowledge take place? The aim here is not to avoid further megaprojects, but rather enable learning processes between them—an area that has not attracted enough interest thus far [

84]. Hence, more research must be conducted on how to cope with these phenomena. We already know why the narratives of successful megaprojects are linked to gentrification and tourism from the perspective of project initiators. We also know where these processes take place and how to frame the observations within the context of neoliberalization, the entrepreneurial turn, etc. However, there is far less knowledge of how to make it better—by both contributing to finding a city’s place in the global urban network, but without fostering polarization, segregation, and other conflicts in their urban arenas. The main problem here is that the planning of megaprojects is so complex that adding social sustainability as a further criterion easily overloads the process, although it should be the main rationale of planning anyway.

Thirdly, a key question is how COVID-19 will affect the relationship between megaprojects, gentrification, and tourism. I see several pandemic-induced turning points, with an impact on each of these phenomena. Due to the current economic recession [

85], a number of projects under construction might face financial difficulties, which endangers their success. Paradoxically, it can be assumed that many cities will feel the need to boost their economies by means of megaprojects, just as in the aftermath of 2008′s economic crisis [

24] or the Asian financial crisis [

80]. I also expect tourism to play a fundamental role in these future projects, based on the strong turn toward tourism as a growth strategy in countries such as Spain after 2008. With regard to gentrification, some scholars expect an even stronger new wave of the process in the aftermath of COVID-19. This so-called “disaster gentrification” [

86] will roll over neighborhoods that are left socially vulnerable not only due to the economic crisis, but also due to renewed austerity programs. This problem is a future line of research with immediate relevance. We will not only need to investigate how to provide appropriate policy instruments to cope with the possible impacts but also how to make large-scale urban development projects (socially) more sustainable in the first place.