Published online Dec 15, 2003. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i12.2880

Revised: September 18, 2003

Accepted: October 12, 2003

Published online: December 15, 2003

Intestinal lymphangiectasia, characterized by dilatation of intestinal lacteals, is rare. The major treatment for primary intestinal lymphangiectasia is dietary modification. Surgery to relieve symptoms and to clarify the etiology should be considered when medical treatment failed. This article reports a 49-year-old woman of solitary duodenal lymphangiectasia, who presented with epigastralgia and anemia. Her symptoms persisted with medical treatment. Surgery was finally performed to relieve the symptoms and to exclude the existence of underlying etiologies, with satisfactory effect. In conclusion, duodenal lymphangiectasia can present clinically as epigastralgia and chronic blood loss. Surgical resection may be resorted to relieve pain, control bleeding, and exclude underlying diseases in some patients.

- Citation: Chen CP, Chao Y, Li CP, Lo WC, Wu CW, Tsay SH, Lee RC, Chang FY. Surgical resection of duodenal lymphangiectasia: A case report. World J Gastroenterol 2003; 9(12): 2880-2882

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v9/i12/2880.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v9.i12.2880

Intestinal lymphangiectasia (IL) is a rare condition with widely variable symptoms and signs. Patients may be asymptomatic or present as vague abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, steatorrhea, edema, chylous pleural effusion, ascites, hypoproteinemia, lymphocytopenia or protein-losing enteropathy[1,2]. IL usually occurs in children or young adults, and is suspected to be caused by a congenital abnormality in the lymphatic system[1-3]. Occasionally, IL can be seen in the aged people, which may be secondary to disorders causing lymphatic obstruction, such as lymphoma, carcinoma, tuberculosis, constrictive pericarditis, retroperitoneal fibrosis, post-radiation effects, and repeated parasite infestation[1,4-6]. Diagnosis depends on characteristic endoscopic findings and pathological features[7-9]. However, it is sometimes difficult to differentiate primary from secondary IL. Surgical intervention may be a final resort to make a definite diagnosis and to relieve symptoms. Herein, we present a case with a solitary duodenal lymphangiectasia presenting as epigastralgia and chronic blood loss. The patient finally received surgical intervention and the symptoms resolved.

A 49-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital in February 1999 with progressive epigastralgia and malaise for 2 months. She had been well in the past and denied family history of systemic disorders. Physical examination showed mild anemic conjunctivae and tarry stool. There was no evidence of significant enteric protein loss.

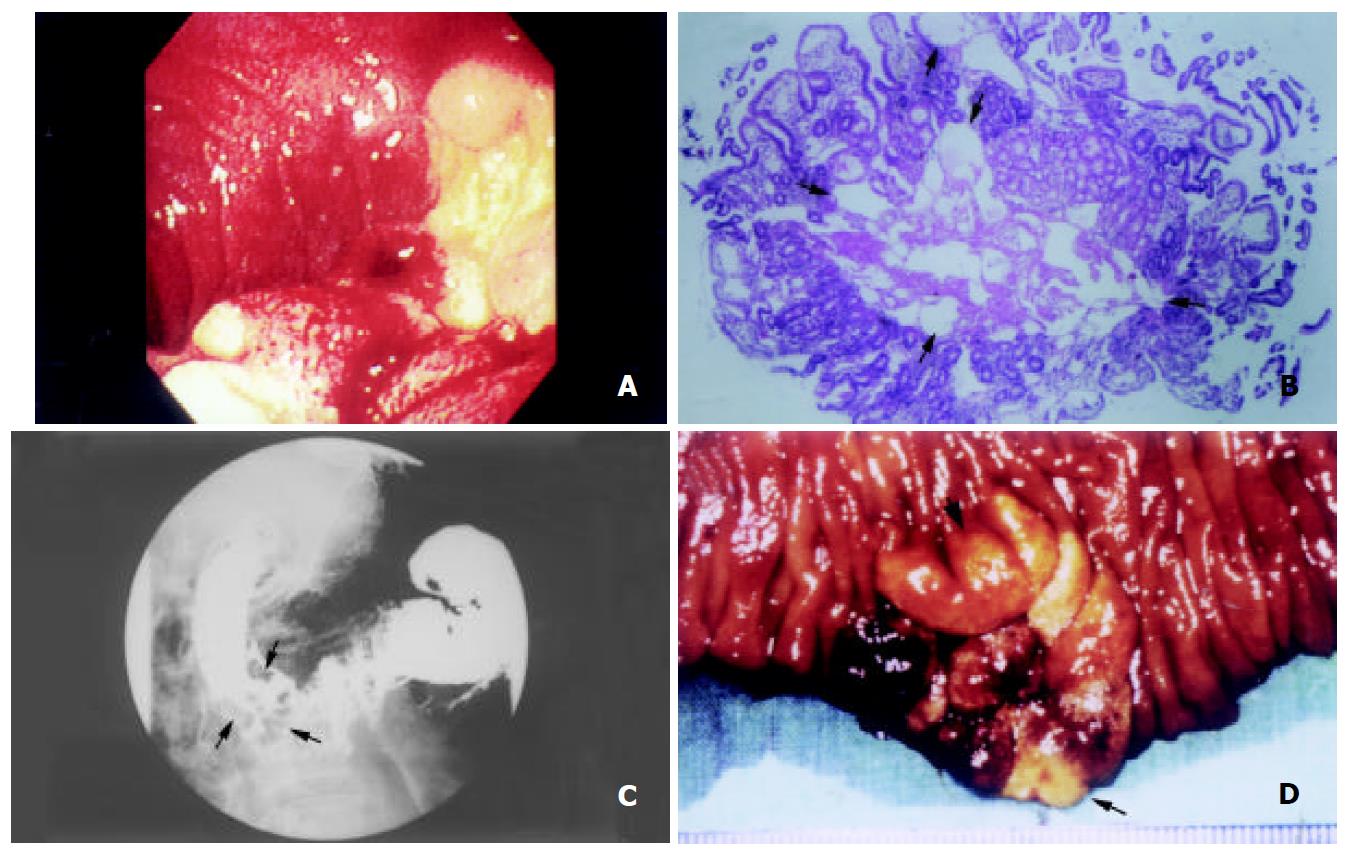

Complete blood count revealed mild normocytic normochromic anemia (hemoglobin 10.5 g/dL). Stool examination disclosed positive occult blood (+++). Serum biochemistries as well as serum concentrations of immunoglobulins and tumor markers, including α-fetoprotein, carcinoembryonic antigen, carbohydrate antigen 19-9, and carbohydrate antigen-125, were all within normal limits. Urinary excretion of 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5-HIAA) was normal. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy showed a 3 cm irregular elevation with bulging border, superficial whitish spots, as well as hemorrhagic and friable mucosa in the second portion of duodenum (Figure 1A). Histological examination showed prominent, dilated lymphatic vessels in the mucosal and submucosal layers (Figure 1B). Upper gastrointestinal barium radiography demonstrated a cluster of polypoid filling defects, 3 × 3 cm in size, in the second portion of duodenum (Figure 1C). Abdominal sonography and computerized tomography (CT) showed no obvious abnormalities. Small intestine series and barium enema did not disclose any lesion. Antacids and a low-fat, high-protein diet supplemented with medium-chain triglycerides were prescribed for one month with no obvious improvement.

For treating refractory epigastralgia and chronic bleeding and excluding underlying diseases, the modified Whipple’s operation with pylorus preservation was carried out in March 1999. A polypoid lesion in the second portion of the duodenum, 3 × 3 cm in size, was found 1 cm lateral to the papilla of Vater (Figure 1D). Pathological examination confirmed it to be an idiopathic lymphangiectasia. No underlying etiologies could be identified. After operation, the patient recovered well. Epigastralgia resolved and the blood hemoglobin returned to normal after surgery and during the later four-years’ follow-up.

Intestinal lymphangiectasia has been well recognized as a disorder characterized by dilated lymphatic vessels of the gastrointestinal tract, especially the small intestine[1-3]. It is a rare condition related to fat malabsorption and protein-losing enteropathy. Distribution of IL can be segmented, multifocal or diffuse. The pathogenesis is believed to be due to obstruction of lymphatic drainage[1-3]. According to the etiologies, IL can be classified into primary and secondary forms[1,2]. Primary IL is usually associated with many genetic syndromes, such as Turner’s syndrome[2,10]. On the contrary, secondary IL is acquired, due to several kinds of gastrointestinal diseases and intra-abdominal or retroperitoneal pathologies, such as carcinoma, lymphoma, tuberculosis or constrictive pericarditis[1,4-6].

Clinical manifestations are similar in both forms of IL, but with variable severity according to the extent of involvement. Some patients can be completely asymptomatic, while at the other extreme, some may be associated with protein-losing enteropathy, growth retardation, or recurrent gastrointestinal tract bleeding[1,2,11]. The protein loss is suspected to be due to rupture of the dilated intramucosal or submucosal lacteals, or exudation from the epithelium[3]. The hemorrhage may be due to rupture of the dilated lacteals, which have potential communications with blood vessels[11].

Diagnosis depends on clinical suspicion. Specific endoscopic findings, accompanied by typical histological pictures can draw into the diagnosis[7]. These endoscopic findings include white-tipped villi, scattered white spots, white nodules, and submucosal elevations[7-9]. Typical histological pictures consist of dilated intramucosal and submucosal lacteals[7-9]. CT scan can help to find the underlying causes of secondary IL[12].

Treatment of IL depends on the severity and extent of involvement. For most patients with primary IL, due to generalized abnormalities and diffuse distribution, dietary modification with a low-fat, high-protein diet and supplementation of medium-chain triglycerides (MCT) is the mainstay of treatment[1,2]. As MCT is absorbed from the portal venous system directly rather than via lymphatics, it may avoid engorgement of the lymphatics, and thus reduce the opportunity for rupture[2]. On the other hand, for patients with secondary IL, the underlying diseases should be treated. Surgical resection can be chosen when IL is confined to a segment of the intestine and has successfully treated protein-losing enteropathy, anemia or abdominal pain in intestine lymphangiectasia[2,13-15].

In this case, an irregularly elevated lesion in the second portion of the duodenum combined with epigastralgia and chronic blood loss was found. Biopsies showed a picture of IL, however, secondary IL could not be excluded. Due to segmental involvement and to rule out underlying causes, surgical resection was performed. The symptoms were relieved and a definite diagnosis of idiopathic duodenal IL was made. In conclusion, surgical resection may be chosen to relieve symptoms and exclude underlying diseases in patients with solitary duodenal IL.

Edited by Zhu LH

| 1. | Rubin DC. Small intestine: anatomy and structural anomalies In: Yamada T, ed. Textbook of gastroenterology. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams Wilkins. 1999;1578-1579. [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 2. | Vardy PA, Lebenthal E, Shwachman H. Intestinal lymphagiectasia: a reappraisal. Pediatrics. 1975;55:842-851. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 3. | WALDMANN TA, STEINFELD JL, DUTCHER TF, DAVIDSON JD, GORDON RS. The role of the gastrointestinal system in "idiopathic hypoproteinemia". Gastroenterology. 1961;41:197-207. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 4. | Nelson DL, Blaese RM, Strober W, Bruce R, Waldmann TA. Constrictive pericarditis, intestinal lymphangiectasia, and reversible immunologic deficiency. J Pediatr. 1975;86:548-554. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rao SS, Dundas S, Holdsworth CD. Intestinal lymphangiectasia secondary to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Dig Dis Sci. 1987;32:939-942. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Oksüzoğlu G, Aygencel SG, Haznedaroğlu IC, Arslan M, Bayraktar Y. Intestinal lymphangiectasia due to recurrent giardiasis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:409-410. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 7. | Abramowsky C, Hupertz V, Kilbridge P, Czinn S. Intestinal lymphangiectasia in children: a study of upper gastrointestinal endoscopic biopsies. Pediatr Pathol. 1989;9:289-297. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Riemann JF, Schmidt H. Synopsis of endoscopic and other morphological findings in intestinal lymphangiectasia. Endoscopy. 1981;13:60-63. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Aoyagi K, Iida M, Yao T, Matsui T, Okada M, Oh K, Fujishima M. Characteristic endoscopic features of intestinal lymphangiectasia: correlation with histological findings. Hepatogastroenterology. 1997;44:133-138. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 10. | Rutlin E, Wisløff F, Myren J, Serck-Hanssen A. Intestinal telangiectasis in Turner's syndrome. Endoscopy. 1981;13:86-87. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Perisic VN, Kokai G. Bleeding from duodenal lymphangiectasia. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66:153-154. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 10] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Fakhri A, Fishman EK, Jones B, Kuhajda F, Siegelman SS. Primary intestinal lymphangiectasia: clinical and CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1985;9:767-770. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 13. | Kingham JG, Moriarty KJ, Furness M, Levison DA. Lymphangiectasia of the colon and small intestine. Br J Radiol. 1982;55:774-777. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jameson JS, Boyle JR, Jones L, Rees Y, Kelly MJ. An unusual presentation of intestinal lymphangiectasia. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1996;11:198-199. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Persić M, Browse NL, Prpić I. Intestinal lymphangiectasia and protein losing enteropathy responding to small bowel restriction. Arch Dis Child. 1998;78:194. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 20] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |