Peer-review started: July 10, 2014

First decision: September 16, 2014

Revised: October 22, 2014

Accepted: December 16, 2014

Article in press: December 17, 2014

Published online: March 9, 2015

Prostatitis comprises of a group of syndromes that affect almost 50% of men at least once in their lifetime and makeup the majority of visits to the Urology Clinics. After much debate, it has been divided into four distinct categories by National Institutes of Health namely (1) acute bacterial prostatitis; (2) chronic bacterial prostatitis; (3) chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) which is further divided into inflammatory and non-inflammatory CP/CPPS; and (4) asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis. CP/CPPS has been a cause of great concern for both patients and physicians because of the lack of presence of thorough information about the etiological factors along with the difficult-to-treat nature of the syndrome. For the presented manuscript an extensive search on PubMed was conducted for CP/CPPS aimed to present an updated review on the evaluation and treatment options available for patients with CP/CPPS. Several diagnostic criteria’s have been established to diagnose CP/CPPS, with prostatic/pelvic pain for at least 3 mo being the major classifying symptom along with the presence of lower urinary tract symptoms and/or ejaculatory pain. Diagnostic tests can help differentiate CP/CPPS from other syndromes that come under the heading of prostatitis by ruling out active urinary tract infection and/or prostatic infection with uropathogen by performing urine cultures, Meares-Stamey Four Glass Test, Pre- and Post-Massage Two Glass Test. Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis is confirmed through prostate biopsy done for elevated serum prostate-specific antigen levels or abnormal digital rectal examination. Researchers have been unable to link a single etiological factor to the pathogenesis of CP/CPPS, instead a cluster of potential etiologies including atypical bacterial or nanobacterial infection, autoimmunity, neurological dysfunction and pelvic floor muscle dysfunction are most commonly implicated. Initially monotherapy with anti-biotics and alpha adrenergic-blockers can be tried, but its success has only been observed in treatment naïve population. Other pharmacotherapies including phytotherapy, neuromodulatory drugs and anti-inflammatories achieved limited success in trials. Complementary and interventional therapies including acupuncture, myofascial trigger point release and pelvic floor biofeedback have been employed. This review points towards the fact that treatment should be tailored individually for patients based on their symptoms. Patients can be stratified phenotypically based on the UPOINT system constituting of Urinary, Psychosocial, Organ-specific, Infectious, Neurologic/Systemic and symptoms of muscular Tenderness and the treatment algorithm should be proposed accordingly. Treatment of CP/CPPS should be aimed towards treating local as well as central factors causing the symptoms. Surgical intervention can cause significant morbidity and should only be reserved for treatment-refractory patients that have previously failed to respond to multiple drug therapies.

Core tip: Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) is difficult-to-treat because of the multitude of potential etiologies that are not easily observed and delayed diagnosis. Pharmacological monotherapy with antibiotics, alpha-blockers and anti-inflammatories provide significant symptomatic improvement in a limited number of patients. Multidrug therapies are recommended for monotherapy refractory patients. Complementary and interventional therapies such as acupuncture, myofascial trigger point release and pelvic floor biofeedback can provide additional symptomatic relief. Current recommendations involve a treatment algorithm based on UPOINT phenotypic presentation for CP/CPPS patients. Keeping in mind the high prevalence of CP/CPPS, development of novel therapies and an effective vaccine for prevention of CP/CPPS is crucial.

- Citation: Khan A, Murphy AB. Updates on therapies for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. World J Pharmacol 2015; 4(1): 1-16

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3192/full/v4/i1/1.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5497/wjp.v4.i1.1

Prostatitis is a term that identifies a number of syndromes ranging from acute or chronic pain to bacterial infection of the prostate gland[1]. Prostatitis makes up the majority of Urology clinic visits with as high as 2 million office visits annually by men suffering from prostatitis in the United States[2] and yet it is one of the least understood diseases in the field. Almost 50% of all men are symptomatic for prostatitis at some point in their lives[3]. Over time diagnostic and therapeutic modalities for prostatitis have evolved significantly and patients are now given specific treatments in accordance with the set of determined subtypes formulated by physicians based on clinical presentations[4].

The national institute of health (NIH) has classified chronic prostatitis into four different categories: Category I: Acute bacterial prostatitis is an infection caused by an underlying uropathogen, which presents with signs of systemic infection including fever and chills. Category II: Chronic bacterial prostatitis is caused by chronic bacterial infection of the prostatitis secondary to recurrent urinary tract infections. Category III: Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CP/CPPS) primarily presents with pain and sometimes presents with voiding symptoms in absence of any urinary tract infection (UTI). It is sub-grouped into two more categories: Category IIIa: Inflammatory CP/CPPS; Category IIIb: Non-Inflammatory CP/CPPS. Category IV: Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis is diagnosed incidentally on prostate biopsy or other pathologic specimen by presence of prostatic inflammation without the evidence of any genitourinary symptoms[5].

The majority of patients with CP/CPPS present with pain symptoms ranging from lower abdominal to ejaculatory pain but the pain is not necessarily associated with lower urinary tract symptoms (LUTS) or sexual dysfunction[6]. Apart from being one of the least understood diseases, CP/CPPS comprises almost 90% of the prostatitis syndromes in patients[7].

Given the high prevalence of the disease and the lack of good diagnostic and treatment strategies, NIH formulated a classification system to stratify the types of prostatitis in order to devise treatment modalities accordingly[8]. The guidelines provided by the NIH in the form of NIH chronic prostatitis symptom index (NIH-CPSI) now serve as the international standard for non-diagnostic symptom evaluation of prostatitis in clinical practice as well as in research protocols (Table 1)[9]. An extensive search on PubMed was conducted for CP/CPPS with an aim to present an updated review on the evaluation and treatment options available for patients with CP/CPPS and to provide an in-depth review of the possible causative factors of CP/CPPS.

| Categories |

| Acute bacterial prostatitis |

| Chronic bacterial prostatitis |

| Chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome |

| Inflammatory |

| Non-inflammatory |

| Asymptomatic inflammatory prostatitis |

CP/CPPS is a syndrome without evident pathophysiology. For long it has been postulated that pathogens are the inciting factors and the early treatments focused on microbial eradication[10]. Recently researchers identified that uropathogens are present for only a few cases, which suggests that other unidentified causative factors play a role in the disease[10] including atypical microbes or pathogens that are difficult to culture[11]. The lack of readily identifiable bacteria rationalized the initial term Chronic Non-Bacterial Prostatitis, which was later changed to chronic prostatitis or CPPS[12]. CPPS is further divided into two types based on the number of leukocytes/high power field on microscopic examination of the expressed prostatic secretion (EPS) or semen. The prostatic fluid leukocyte count is used to differentiate between CPPS type IIIa (5-10 leukocytes/hpf) and type IIIb (< 5 leukocytes/hpf)[13]. Type IIIa CP/CPPS patient samples also have higher levels of pro-inflammatory markers, which are absent in type IIIb[12]. Despite the absence of bacteria in patients with CP/CPPS, it is hypothesized that bacterial infection acts as the initiating factor for the development of the disease.

CP/CPPS has also been linked to depression, and similar conditions with chronic pain symptoms such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and irritable bowel syndrome[14,15].

Efforts have been put into finding the role of sexually transmitted pathogens such as Chlamydia trachomatis, trichomonas vaginalis, Ureaplasma urealyticum or mycoplasma hominis in causing CP/CPPS but no researcher yet been able to link the two[16]. A notion passed on by the researchers is that Bacterial involvement in CP/CPPS is only in 10% of the patients made evident by their response to antibiotics[17].

Atypical bacteria’s haven been implicated as one of the potential precipitants of the pathogenic process in CP/CPPS. Atypical bacteria’s are difficult to cultivate and require amplification at molecular level hence there’s an important role of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in the investigation[18]. Using PCR Hochreiter et al[19] were able to identify the presence of 16 s sub-unit of ribosomal RNA in CP/CPPS patients who had previously been cultured without evidence of bacterial growth in culture media.

Ever since Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) has been established as causative for diseases other than gastric ulcers, researchers have been investigating its contribution in development of CP/CPPS. One such study by Karatas et al[20] looked for H. pylori seropositivity in CP/CPPS patients. They found that 76% of the cases were seropositive for H. pylori as compared to 62% controls. They posit a possible role of H. pylori in CP/CPPS, but large multicenter studies are necessary to establish a firm link between the two.

An atypical Escherichia Coli strain known as CP1 has been associated with CP/CPPS. As this strain was isolated from a patient suffering from CP/CPPS, non-obese diabetic (NOD) mice were inoculated with CP1 to assess its role in the disease. CP1 was found to be invasive into the urothelium and could chronically colonize the urinary tract of the mice and initiate pain as seen in the patients of CP/CPPS[21].

Much work has gone into elucidating the role of the immune system in the pathophysiology of CP/CPPS[22]. One of the cells thought to play a major role are mast cells, which are derived from CD34+ hematopoietic precursor cells. Mast cells carry and release potent pro-inflammatory and vasoactive substances such as histamine, serotonin, proteases, leukotriene’s and nerve growth factor (NGF)[23,24]. Seminal NGF levels are a reliable predictor of mast cell activity and increased levels are linked to increased pain symptoms, suggesting that NGF is a possible pain inducer[25]. A study was conducted in which EPS from patients diagnosed with CPPS IIIb was compared to controls. Samples were assayed for mast cell tryptase and NGF levels. It was shown that patients diagnosed with CPPS IIIb had significantly increased levels of tryptase and NGF in their prostatic fluid[25]. Interestingly increased tryptase-PAR2 axis activity is linked to pain in animal models through the activation of the dorsal root ganglion[26].

It has been demonstrated that T cells can provoke prostatic and pelvic pain in the absence of any ongoing bacterial infection. In a study, interleukin-17a (IL-17a), which is secreted primarily by Th1 helper cells, was shown to induce pain symptoms in murine models without interferon γ (IFNγ) playing any major role in the process indicating that T cells are primary mediators of pain in the mouse CPPS model[27].

Autoimmunity has been considered as a possible cause of CP/CPPS since autoreactive T-cells have been found within the prostate, which can trigger IFNγ release[22]. Recently a study was conducted to assess the role of autoimmunity in the development of CP/CPPS in an experimental autoimmune prostatitis model in NOD mice. The study demonstrated that Th1/Th17 cells expressing CXCR3 receptors were able to infiltrate and damage the prostate gland through the induction of pro-inflammatory chemokines[28]. Several pro-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1b, -6 and -8, tumor necrosis factors α and IgA have been linked to the development of CP/CPPS following an event that triggers initiation of the inflammatory process[29].

Chemokines appear to play a significant role in the development of the CP/CPPS. Chemokines are a subgroup of cytokines responsible for regulating and recruiting inflammatory cells; of them, two chemokines, monocyte chemotactic protein 1 (MCP-1) also known as C-C motif ligand 2 and macrophage inflammation protein 1α also called C-C motif ligand 3 can enhance the pain symptoms of CPPS moreover both chemokines are elevated in CP/CPPS type IIIa and type IIIb patients[28,29].

Despite the presence of inflammatory markers in the EPS, Thumbikat et al[30] observed in their study that MCP-1 has no chemoattractant potential in CP/CPPS patients; the underlying mechanism can be caused by extracellular proteases and induced chemoattractant signal loss. In other words, the normal inflammatory pathway is altered within the patient’s prostate and this aberrant inflammatory pathway is playing part in pathogenesis of the disease.

Neurological dysfunction has been a major focal point for the etiology of the pain in CP/CPPS. A group of men diagnosed with CP/CPPS found to have high amounts of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) present in their prostatic fluid were treated with antibiotics (Quinolones or Macrolides) and anti-oxidants (Prosta-Q). Subsequently, the level of PGE2 decreased by 50% and β-endorphin levels concurrently increased 2.75 fold, which coincided with reported improvement in patient’s pain using the NIH-CPSI[31]. This provided quantifiable effects presumedly due to local neurological effects of prostaglandins along with its role in inhibition of β-endorphins[32].

NGF is a known neurotrophic agent that has a direct role in pain induction in CP/CPPS patients[33]. Prostate inflammation leads to the release of cytokines such as IL-10, which may induce the expression of NGF[33] or direct neuronal damage may bring about NGF release, prompting excitation of C-fibers and mast cell degranulation leading to further release of NGF[34]. Though NGF is released peripherally, it can sensitize central neurons once its concentration exceeds a threshold causing constant depolarization of those neurons. This, in turn, leads to central hyper-sensitization and chronic pain[32].

Furthermore, autonomic dysfunction has been implicated in patients with CP/CPPS as a key contributor in the network of processes promoting symptom development. Abnormal postural blood pressure response has been noted in CP/CPPS patients, along with elevated peripheral blood pressure readings[35]. Cho et al[36] also reported that CP/CPPS patients had lower heart rate variability as compared to the controls, which suggests that autonomic dysfunction could be a causative as well as an aggravating factor in CP/CPPS.

Recently, compelling results have been obtained highlighting the role of nanobacteria in CP/CPPS. Nanobacteria are newly discovered cell-walled organisms that have an annular structure, display slow growth in cell culture, are able to induce cell death in fibroblasts and require electron microscopy for visualization[37]. They do not require host cells in order to replicate and are believed to form the apatite core of prostatic calculi, as under physiological conditions they are present in mineralized apatite crystal form[36-38]. A study was performed to establish the treatment modalities that can be effective against nanobacteria-causing CP/CPPS in the presence of prostatic calculi; in this study patients refractory to multiple prior therapies were given tetracycline, multivitamin (Nanobac OTC supplement) and an ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid rectal suppository for 3-4 mo. Ultrasound and nanobacterial antigen testing was done before the treatment process was initiated. Patients reported marked improvement in their mean NIH-CPSI score (P < 0.0001), after 3 mo consequently few patients who underwent transrectal ultrasound displayed decreased or absent prostatic stones once the treatment was completed[38].

The process of CP/CPPS appears to begin after an initiator causes inflammatory or neurogenic damage within or outside the prostate[39]. An important consideration in CP/CPPS patients is that similar symptomatology can also be seen in patients with bladder neck obstruction and external sphincter dyssynergia[40]. These patients often complain of dysfunctional voiding. It is hypothesized that psychological stress causes aberrant pelvic floor muscle function which triggers dysfunctional voiding and eventually full-blown CP/CPPS[41-43]. There is evidence that increased intraprostatic pressure due to enhanced sympathetic activity and can lead to urine reflux from the urethra into prostate, which subsequently causes prostatic inflammation[44]. The prostatic inflammation is thought to cause edema that disrupts the microvasculature, causing tissue hypoxia and pain initiation[45].

A study by Shoskes et al[46] demonstrated myofascial pain as an etiology of CP/CPPS. They deduced that most of the patients with CP/CPPS had point myofascial tenderness with the prostate being the tenderest point. Although the cause of myofascial spasm can be infectious, inflammatory or traumatic like CP/CPPS, there was no association between the myofascial spasm and prostatic inflammation. Neuromuscular trigger points have been identified in CP/CPPS patients and it is hypothesized that painful myofascial tissue plays a major role in the syndrome[47].

A racially and ethnically diverse study known as the Boston Area Community Health survey comprised of 2301 men was conducted by Daniels et al[48] between April 2002 through June 2005, demonstrating men with frequent UTI’s had higher odds of having symptoms of CP/CPPS (P < 0.01). Similarly a study conducted to investigate the symptoms of prostatitis amongst male health professionals concluded that individuals with a history of sexually transmitted disease had 1.8 times increased odds of having the disease[49].

Patients with CP/CPPS primarily complain of pain in the pelvic region including perineum, rectum, prostate, penis, testicles and abdomen. Along with the pain occasionally patients also complain of LUTS or obstructive symptoms[50]. Pain lasting longer than 3 mo[51] is an imperative symptom and is the most consistent finding in CP/CPPS patients[6]. Patients also experience a wide array of sexual dysfunctions including erectile dysfunction, painful ejaculation and premature ejaculation[52].

Diagnosing CP/CPPS can be difficult as there are no validated tests for the disease and it is largely a diagnosis of exclusion[53] once other disease such benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), interstitial cystitis, Genitourinary stones or cancer and prostatic abscess have been ruled out[54]. Adequate history, a physical examination including a digital rectal examination and urinalysis are mandatory in every patient[55]. Physicians are advised to adopt a step-by-step approach (Table 2) including subjective evaluation and quantification of pain symptoms using the NIH-CPSI followed by physical evaluation and laboratory tests while investigating a patient for CP/CPPS[56]. Meares-Stamey-four glass[57] and the modified two glass tests[13] are commonly used laboratory investigations.

| Primary evaluation |

| History: Should include complete background and symptom evaluation |

| Physical exam: Complete physical exam including a digital rectal exam and check for myofascial tenderness |

| Pain evaluation: Use the National Institute of Health-Chronic Prostatitis Symptom index for quantification of the symptoms |

| Urinalysis and culture |

| Specialized evaluation |

| Meares-stamey four glass test |

| Pre and post-massage two glass test |

| Urodynamic studies (only if lower urinary tract symptoms or outflow obstruction present) |

| New/optional evaluation |

| Serum prostate-specific antigen |

| Prostatic fluid nerve growth factor levels |

| Cystoscopy |

| Transrectal ultrasound or computerized tomography scan |

| Intra-anal electromyography |

| Pelvic floor ultrasound |

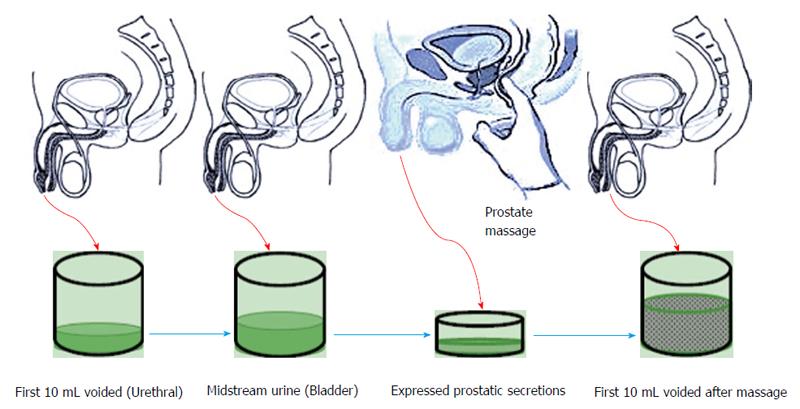

This test involves performing a prostatic massage followed by collection of four samples of Urine and expressed prostatic fluid. Each sample collection takes place after voided bladder 2 (VB2) has been collected. Initial 10 mL of voided urine constitutes urethral flora. Subsequently 200 mL of urine is voided and midstream urine is collected (VB2) this constitutes the bladder flora. Collection of VB2 is followed by a prostatic massage to collect EPS afterwards EPS and the first voided 10 mL are collected (VB3) (Figure 1). These samples are cultured and evaluated microscopically to look for bacterial presence and confirm prostatic inflammation[58]. Meares-stamey test can help differentiate between type II, IIIA and IIIB on the bases of presence of leukocytes (> 5 in IIIA and < 5 in IIIB)[50].

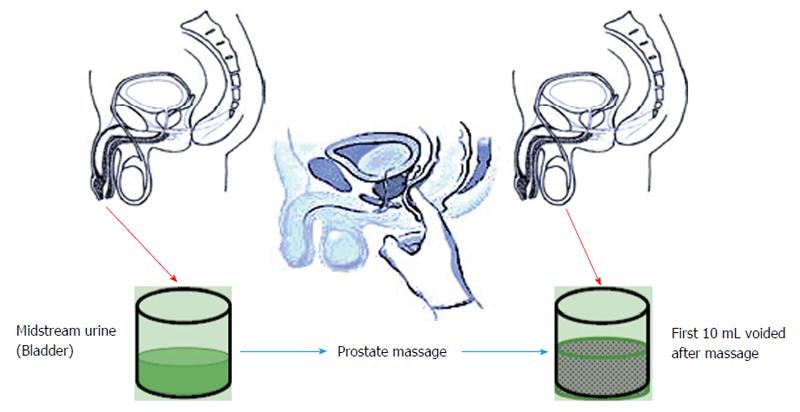

Meares-Stamey four-glass test was modified to pre and post-massage two-glass test (Figure 2), which utilizes only VB2 and VB3 and provides fairly accurate results. Along with being cost effective it is easier to perform[59].

Studies have been conducted to find a link between CP/CPPS and total or free prostate-specific antigen (PSA) but a statistically significant connection is yet to be established between the two[60,61]. PSA levels should be checked even without the presence of pain in patients older than 50 years.

As discussed earlier a positive correlation between nerve growth factor levels and NIH-CPSI score have been found, presence of higher levels of NGF in CP/CPPS than control group further strengthens the use of NGF as a biomarker[62]. Higher levels of NGF in seminal fluid of CPPS patient heralds prostatic inflammation[33] hence it can be used to assess treatment response in the patients.

CP/CPPS patients are not required to undergo unnecessary imaging or endoscopic studies until and unless there is evidence of LUTS or bladder outflow obstruction in which case urodynamic evaluation helps guide treatment[56]. Pelvic imaging such as transrectal ultrasound, computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging can be helpful in ruling out bladder, prostate, seminal vesicular or ejaculatory duct pathology[55]. As pelvic floor muscle dysfunction has been contemplated as one of the possible causes of CPPS, intra-anal electromyography and pelvic floor ultrasound has successfully been used to assess higher pelvic resting muscle tone[63].

Antibiotics: Despite the fact that bacterial involvement is one of the least likely causes of CP/CPPS and there are apprehensions surrounding the etiology of CP/CPPS, the treatment primarily constitutes of empirical therapy and in it antibiotics are amongst the most prescribed medications. In a some patients with bacteria identified as the primary etiological factor in causing the disease the antibiotic therapy helps improve symptoms by eradicating the pathogen, however the conducive effects of antibiotics have largely been linked to their anti-inflammatory activity[17].

A randomized multicenter trial by Alexander et al[64] conducted to analyze the effect of ciprofloxacin over the period of 6 wk in 49 patients, did not result in any statistically significant improvement in the NIH-CPSI score. Another study conducted to infer efficacy assessment of levofloxacin[65] proved to be fruitless in exhibiting significant improvements in patients NIH-CPSI score on the other hand a course of tetracycline over the period of 12 wk did prove efficacious but the study had lacking in several fronts including small patient population and use of combination therapy[38]. Despite the negative outcomes of the above studies, a study undertaken by Canadian Prostatitis Research Group did show promising results with likelihood of symptom improvement being almost 65% after a 12-wk course of ofloxacin was administered to CP/CPPS patients[66].

Recently Choe et al[67] performed a multicenter randomized pilot trial to compare the effect of roxithromycin with ciprofloxacin and aclofenac in 75 patients divided into three groups. Patients were treated for 4 wk and subsequently followed for 12 wk. Results obtained showed decrease in NIH-CPSI score in roxithromycin group comparable to results of the other two groups for type IIIA patients and even lower scores in type IIIB patients. This outcome supports the notion that though CP/CPPS is considered primarily to be a non-infectious condition, post-antibiotic improvement in symptoms attests their definitive role in disease treatment.

Use of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxizole has also been found to improve symptoms in CP/CPPS[68] and a single 4-6 wk course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxizole can be tried as a first line treatment therapy[58]. In a small study, Zhou et al[69] found out that tetracycline was able to improve the mean NIH-CPSI scores from 35.6 ± 5.2 to 17.1 ± 2.8 in the treatment group (P < 0.01). This result warrants performing further investigations to evaluate the effects of tetracycline therapy in CP/CPPS. Antibiotic use is recommended only in antibiotic naive population and should not be considered as a monotherapy in patients who had prior antibiotic treatment. (Evidence level: 1, recommendation grade: A).

Anti-inflammatories: As prostate inflammation is one of the possible etiologies of CP/CPPS, the use of anti-inflammatories to curb the inflammation has been a mainstay of treatment and plays a discrete role in disease management. Mast cells are considered to play an important part in pathological process of CP/CPPS for this reason a small-randomized single center study conducted to identify the effect of a leukotriene inhibitor zafirlukast did not exhibit promising results[70]. Cycloxygenase inhibitors are an important class of drugs with important anti-inflammatory effects. Rofecoxib, a COX-2 inhibitor, was given to 161 patients. Efficacious effects were seen in the treatment group against the placebo group but only at high doses given to the patients over a span of 6 wk[71]. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs have been commonly used in the treatment of CP/CPPS as a first line therapy[72]. Few trials are available, one of which was conducted by Tuğcu et al[73] who treated CP/CPPS patients with Ibuprofen together with doxazosin and thiocolchicoside (muscle relaxant) as a triple therapy and compared the results with alpha blocker (Doxazosin) monotherapy and placebo groups for six months, which displayed mean improvement of NIH-CPSI score from 23.1 to 10.7 in the triple therapy group and 21.9 to 9.2 in the the monotherapy group with a stable score in the placebo group indicating there is no advantage of triple therapy over mono therapy (P < 0.05) in CP/CPPS. Similarly, a placebo controlled study to assess the role of celecoxib in CP/CPPS by Zhao et al[74] determined that 6 wk of celecoxib therapy reduced total NIH-CPSI score from 23.91 ± 5.27 to 15.88 ± 2.51, a statistically significant decrease in score (P < 0.006).

Pentosan polysulfate sodium is a FDA approved glycosaminoglycan used in interstitial cystitis chiefly because of its anti-inflammatory effect on bladder mucosa[75]. A 16-wk randomized double-blinded multicenter study failed to show its substantial effect in improving NIH-CPSI scores in CP/CPPS patients[76]. There is an ample room for research and large multicenter studies would certainly reveal more information regarding the potential effects of pentosan in CP/CPPS patients. Keeping in mind the pathogenic role of neurotrophin Nerve growth factor in CP/CPPS, a randomized double-blinded multicenter study was conducted with 62 patients divided in two groups to evaluate the efficacy of tanezumab a humanized monoclonal antibody. Tanezumab was given as a single 20 mg intravenous dose per day to the treatment group for 6 wk but only modest response was observed as compared to the placebo group[77]. These results warrant further trials on a larger scale to broaden the scope of the available treatment options.

Anti-inflammatories play an important role in CP/CPPS therapy when given as a part of the multimodal regimen. (Evidence level: 2, recommendation grade: C).

Alpha-adrenergic blockers: Often, men suffering from CP/CPPS also present with LUTS such as urgency, frequency and incomplete voiding. These manifestations along with the fundamental CP/CPPS symptom of genitourinary pain give way to the use of α-blockers. Alpha blockade is thought to exert its pacifying effects on prostate, urethra and bladder neck and in turn improve the LUTS along with improvement in NIH-CPSI scores especially in alpha-blocker-naive patients[78]. Various randomized placebo controlled trials have been performed to ascertain effects of alpha-blockers in CP/CPPS. Alpha-blockers commonly used to minimizing LUTS in CP/CPPS are alfuzosin[79,80], tamsulosin[64,81], terazosin[82], doxazosin[73] and silodosin[83]. Despite the fact that two NIH-sponsored studies failed to demonstrate any usefulness of alfuzosin or tamsulosin in CP/CPPS[84], beneficial effects of alpha blockers are pertinent to their long term use as illustrated in a randomized placebo control study by Nickel et al[80] performed to evaluate the role of alfuzosin against placebo in recently diagnosed alpha-blocker naive CP/CPPS patients over a period of 12 wk. The study failed to demonstrate any significant improvement in the NIH-CPSI score of the group treated over the placebo group and postulated that long-term therapy might be warranted to observe treatment effects. Taken together, alpha-blocker monotherapy is not recommended, especially in patients previously treated with alpha-blockers. (Evidence level: 1, recommendation grade: A).

Combination therapy trials: Due to the complex nature of the disease, lack of effectiveness of monotherapies and the postulated role of multiple patho\genic factors for CP/CPPS, various combination therapies have been devised by researchers to address specific etiologic factors. The three A’s of CP/CPPS including alpha-blockers, anti-inflammatories and antibiotics are an effective combination therapy for CP/CPPS[85]. A recent meta-analysis of all the available treatments for CP/CPPS and their subsequent effects on patient NIH-CPSI scores reported multimodal therapy with alpha-blockers, anti-inflammatories and anti-biotics was superior to monotherapies for optimal disease management[72]. Combination therapies with alpha-blockers and anti-biotics have revealed positive outcomes[64,86], but current recommendations are to tailor the treatment regimen to the patient’s symptoms. (Evidence level: 2, recommendation grade: A).

Phytotherapy: Phytotherapy is one of the alternative pharmacotherapies believed to abate the inflammatory process that occurs in the prostate, but the exact mechanism is still unknown[87]. Phytotherapy includes pollen extracts, quercetin and saw palmetto. Various pollen extract preparations are available. In one randomized double-blinded trial, 60 patients were divided into treatment groups that received prostat/poltit (a pollen extract) or placebo. After 6 mo, the pollen treatment group reported marked improvement in symptom scores compared to placebo group[88]. A larger randomized, multicenter, placebo-controlled trial by Wagenlehner et al[89] enrolled 139 participants, randomly allotted to treatment and placebo groups. The 12-wk study resulted in improvement in pain (P = 0.0086), quality of life (P = 0.0250) and NIH-CPSI score (P = 0.0126) in the Pollen extract group. These studies highlight the fact that pollen extract to some extent is effective in the treatment of CP/CPPS. (Evidence level: 1, recommendation grade: B).

Quercetin is a bioflavonoid found in plants, as well as in green tea, onions and red wine and is a known anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory agent[90]. A prospective placebo controlled, double-blind trial by Shoskes et al[91] demonstrated mean improvement of NIH-CPSI score from 21.0 to 13.1 (P = 0.003) in the group taking quercetin. Apart from the quercetin and placebo group, a third group received a quercetin formulation mixed with digestive enzymes bromelain and papain. This group demonstrated an 82% improvement in mean NIH symptom scores from 25.1 to 14.6. (Evidence level: 2, recommendation grade: C)

Saw Palmetto (Serenao repens), a herbal lipid extract, is one of the most frequently used phytotherapies in symptomatic benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) patients[92,93], but its use in CP/CPPS still remains controversial because of limited number of trials. A prospective, randomized open-label study by Kaplan et al[94] compared saw palmetto with finasteride, 5-alpha reductase inhibitor, in 64 participants. After 1 year, mean NIH-CPSI score in the finasteride group decreased from 23.9 to 18.1 (P = 0.003) and from 24.7 to 24.6 (P = 0.41) in saw palmetto group. These authors concluded that the use of saw palmetto does not improve the symptoms in CP/CPPS patients significantly. (Evidence level: 3, recommendation grade: C).

Neuromodulatory drugs: Neurological dysfunction has been implicated as a prime culprit in men with CP/CPPS. Depression and psycho-emotional changes usually accompany neurogenic pain in CP/CPPS[95,96]. Thus, anxiolytics and anti-depressants might have a therapeutic role in disease management. Several uncontrolled trials have been performed to evaluate different pharmacological interventions for neuropathic pain symptoms. Recently, Giannantoni et al[97] conducted a small study to analyze the effectiveness of duloxetine being given as part of a multidrug regimen for CP/CPPS. After 16 wk of treatment in 38 men, randomly divided into two groups, one of which received an alpha-blocker (Tamsulosin) and saw palmetto, while the other group received triple therapy with an alpha-blocker (Tamsulosin), saw palmetto and duloxetine. Significant improvement in total NIH-CPSI score (25.1-14.17, P < 0.01) was observed in the group receiving the triple therapy. The anticonvulsants pregabalin and gabapentin play a major role in chronic pain syndromes treatment and also have been used in CP/CPPS[98]. A multi-center randomized double-blinded placebo controlled trial failed to show significant NIH-CPSI score improvement in participants receiving pregabalin[99]. Nonetheless well-controlled studies are required to investigate possible benefits of these drugs in the management of CP/CPPS. Neuromodulatory drugs should not be recommended as a primary treatment modality for CP/CPPS (Evidence level: 2, recommendation grade: B).

Hormonal therapy: Finasteride is a 5-α reductase inhibitor used as a treatment to alleviate symptoms and prevent surgical intervention in men with BPH[100]. It blocks the conversion of testosterone to the more potent dihydrotestosterone. The use of finasteride in CP/CPPS needs further study because of the lack of data that supports its positive role in improving patient symptoms. Nickel et al[101] conducted a placebo-controlled, randomized trial to determine the effectiveness of finasteride in reducing CP/CPPS symptoms. Only 75% of participants receiving finasteride had > 25% improvement in the subjective oral assessment and a similar trend was observed in the NIH-CPSI scores. Use of mepartricin, an estrogen-lowering drug[102], has been tested in a small placebo controlled trial. It was found to be effective in decreasing the NIH-CPSI score from 25.0 to 10.0 in the treatment group along with a statistically significant decrease in scores of pain (11.0-4.0) and quality of life (10.0-5.0)[103]. Despite the fact that this study displayed some benefit of mepartricin in CP/CPPS patients, larger multicenter center studies are still required to confirm the results. Hormonal therapy is not considered as a first line treatment in CP/CPPS and should be reserved in patients with symptoms of BPH (Evidence level: 2, recommendation grade: C).

Others: Recently a 12-mo randomized placebo controlled double-blinded study was conducted to observe the effects of immunostimulation in CP/CPPS by giving an oral immunostimulatory agent known as OM-89, which is a lysed pathogenic E. coli extract[104]. The study did not demonstrate a significant difference in improvement of NIH-CPSI scores between the treatment and the placebo groups despite the fact that the long term therapy was well tolerated by the patients[105]. Hormonal therapies as yet are only advisable to patients with CP/CPPS with prior symptoms of prostatic hyperplasia. Use of allopurinol[106,107] and oral corticosteroids[108] in the management of CP/CPPS remains uncertain and their effects have not comprehensively studied and more detailed and well planned trials are necessary to ascertain the therapeutic role these drugs. (Evidence level: 3, recommendation grade: C).

Physical therapy, myofascial trigger point release and pelvic floor biofeedback: Large number of patients with CP/CPPS also have pelvic floor muscle dysfunction[109] and myofascial pain. In order to relax these pelvic muscle and decrease the pain associated with hypersensitive regions in muscles or fascia, pelvic floor physical therapy and myofascial trigger point release has been devised. Researchers from stanford have identified various myofascial trigger points[47] and have devised a protocol accordingly employing myofascial trigger point release physical therapy along with paradoxical relaxation technique in CP/CPPS patients. The beneficial effect of this treatment can be assessed by one of their trials which resulted in a 72% rate of moderate to marked improvement of symptoms along with improvement in NIH-CPSI scores with a median decrease of 10.5 (P < 0.001) in markedly and 6.5 (P = 0.008) in moderately improved groups of CP/CPPS patients[110].

A randomized, multi-center, feasibility trial performed by FitzGerald et al[111] evaluated the effectiveness of physical therapy in urological chronic pelvic pain syndromes with global therapeutic massage (GTM) vs myofascial physical therapy (MPT). In the study, 45% participants had CP/CPPS and 42% received GTM and 48% received MPT. MPT resulted in improved symptom scores (P = 0.0003) in CP/CPPS patients but was only significantly better than GTM on the urinary symptom scale of the NIH-CPSI (-3.9 vs -0.3, P = 0.007).

Along with myofascial trigger point release, the rationale behind physical therapy is to restore proper use of pelvic floor muscles. Pelvic floor biofeedback and pelvic floor re-education were investigated by Cornel et al[112] in a study using rectal Electromyogram probes to monitor therapy response. Pelvic floor biofeedback helped improve the NIH-CPSI score from 23.6 to 11.4 (P < 0.001) along with a decreased pelvic muscle tone (P < 0.001). Similarly He et al[41] used pelvic floor biofeedback in 21 patients and attained comparable results with improvement in NIH-CPSI score (P < 0.05) along with improvement urodynamics (P < 0.05). Nadler[113] had previously demonstrated the beneficial effects of biofeedback and bladder training in CP/CPPS patients in a small pilot study. Overall, these results point towards therapeutic benefit when targeting pelvic floor muscle dysfunction for CP/CPPS patients.

Acupuncture: Acupuncture has been put forward as a safe and beneficial procedure for CP/CPPS patients. Recently several publications have evaluated the role of acupuncture[114-117], though the exact mechanism of pain relief is unknown. But, its utility in other neuropathic pain entities has already been established[114]. A recent review found acupuncture effective in ameliorating CP/CPPS pain symptoms and the authors endorsed acupuncture as part of a standard CP/CPPS treatment[118].

A pilot study to determine the validity of acupuncture use to improve CP/CPPS symptoms was performed. Chen et al[115] provided acupuncture therapy for 6 wk in men refractory to standard therapy. Total NIH-CPSI score decreased from 28.2 to 8.5. The NIH-CPSI pain (14.1-4.8), urinary (5.2-1.3), and NIH-CPSI quality-of-life (8.8-2.3) scores all decreased after a median follow-up of 33 wk. Although this had significant limitations including small study population and the lack of control and placebo groups, acupuncture achieved impressive results and highlighted a need for randomized placebo controlled studies. Lee et al[116] compared acupuncture with sham acupuncture and found out that 32 (73%) of 44 participants responded with 4.5 points decrease in NIH-CPSI score on average in the acupuncture group compared to the score of 21 (47%) participants in the sham group (P = 0.03). After 24 wk 32% participants in the acupuncture group demonstrated long-term response as compared to 13% participants (P = 0.04) in sham acupuncture group without any additional treatment.

Electroacupuncture was noted to significantly reduce NIH-CPSI scores (details) at 6 wk compared to sham electroacupuncture and to medical advise and exercise regimens[119].

In a recent randomized double-blinded trial, results of acupuncture and sham acupuncture in CP/CPPS were compared over the period of 10 wk. In sham acupuncture, participant’s short needles were placed 0.5 cm away from the true acupuncture points. Clinical response criterion was achieved in 73% of the acupuncture participants compared with 47% of sham acupuncture participants (P = 0.017). Higher levels of β-endorphins and leucine-enkephalin levels were noted in the acupuncture group (P < 0.01)[117]. A recent systemic review analyzed 27 clinical trials including 890 patients and concluded that acupuncture can be contemplated as an efficacious treatment modality in CP/CPPS[120]. Nevertheless, high quality randomized, placebo-controlled trials are needed to investigate acupuncture as a first-line treatment modality for CP/CPPS.

Posterior tibial nerve stimulation and sacral neuromodulation: United States Food and Drug Administration has approved sacral nerve stimulation and posterior tibial nerve stimulation for use in CP/CPPS patients with urinary symptoms. Despite the fact that these therapies have been approved, they are still not considered first line treatments[121]. Both therapies have improved NIH CPSI scores, but larger and better-designed multicenter trials are still required in order to include them into the treatment algorithm[122-124].

Botulinum toxin injection: Botulinum toxin is a potent neurotoxin already being used in different muscular and neurological disorders. Likewise its use has been advocated in the treatment of CP/CPPS patients when multi-therapy is employed[125].

Others: Several other techniques including prostatic massage, sitz bath and frequent ejaculations are prescribed, but they only have a supportive role in the treatment of CP/CPPS. Nickel et al[126] devised a comprehensive 8-wk program consisting of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in patients with CP/CPPS in order to help the patients manage their condition and in turn improve their quality of life (QoL). This technique was again tested by Tripp et al[127] and obtained satisfactory results. Patients displayed improved scores in the categories of pain, disability and catastrophizing. Follow-up CPSI scores were significantly decreased (P = 0.007) in particular, significant decrease was noted in CPSI pain (P = 0.015) and QoL domains (P = 0.013). These results support the use of CBT, but additional randomized controlled trials are required to assess its long-term effects in CP/CPPS patients.

These interventions are helpful in CP/CPPS patients with pelvic floor muscle dysfunction and help relieve the symptoms significantly (Evidence level: 4, recommendation grade: C).

Surgical treatments have been found to help patients suffering from CP/CPPS refractory to other types of treatments. Various types of surgical interventions are available but their level of benefit is still questionable.

Transurethral needle ablation: Transurethral needle ablation (TUNA) is already one of the primary treatment methods with clinical efficacy BPH/LUTS[128]. Its therapeutic effect in CP/CPPS is yet to be determined because of the limited number of studies available. A Pilot study performed by Aaltomaa et al[129] along with the studies conducted by Lee et al[130] and Chiang et al[131] have shown favorable outcomes in the patients, but further prospective trials are still required[130].

Transurethral balloon dilation: Transurethral balloon dilation (TUBT) is another treatment modality offered to CP/CPPS patients, though, as in the case of TUNA, limited number of studies only allows TUBT to be offered as a secondary treatment choice. A small study by Lopatin et al[132] performed TUBT on 7 patients presenting with bladder neck or prostatic urethra obstruction which improved the overall symptoms of CP/CPPS in all the participants.

Transurethral microwave therapy: Transurethral microwave therapy (TUMT) is one of the primary treatments BPH. In CP/CPPS patients, TUMT have been used and results obtained are promising though its use as a first line therapy is not recommended[5].

Extracorporeal shockwave therapy and Extracorporeal magnetic stimulation: Most recently, extracorporeal shock wave therapy has been shown to have potential benefit in CP/CPPS patients. Zimmermann et al[133] followed 34 patients for 12 wk and found significant improvement in patients pain and QoL. They followed their initial trial with a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized trial with 60 patients. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy was significantly effective in improving pain, QoL and voiding symptoms[134].

Kim et al[135] used a recent technique known as extracorporeal magnetic stimulation to treat CP/CPPS. In their study 46 patients were enrolled and the treatment was provided for 6 wk. The patients were followed 24 wk post treatment. More than 70% of the patients registered a positive outcome of the treatment with an improvement in NIH-CPSI (P < 0.05) and pain scores (P < 0.05). Results for this study are promising but it would be too early to say if it can be included as a primary mode of treatment until and unless more multicenter trials are performed and validate its effectiveness.

The above interventions are reserved for patients with refractory symptoms and should not be offered as first line treatment modality (Evidence level: 2, recommendation grade: A).

Transurethral resection of prostate and Prostatectomy: Transurethral resection of prostate and prostatectomy have been reserved only for CP/CPPS patients with intractable pain and is not routinely recommended because it involves significant morbidity and persistence of symptoms post-surgery[39,96] (Evidence level: 4, recommendation grade: D).

CP/CPPS is a heterogeneous syndrome, which makes it difficult to treat. Monotherapies have worked in some of the patients, but there is no data to support the use of a single therapy in most patients. Monotherapy failed to find major success in treating the disease because it acts against a single target but there are multiple etiologies that likely lead to the development of the disease[136].

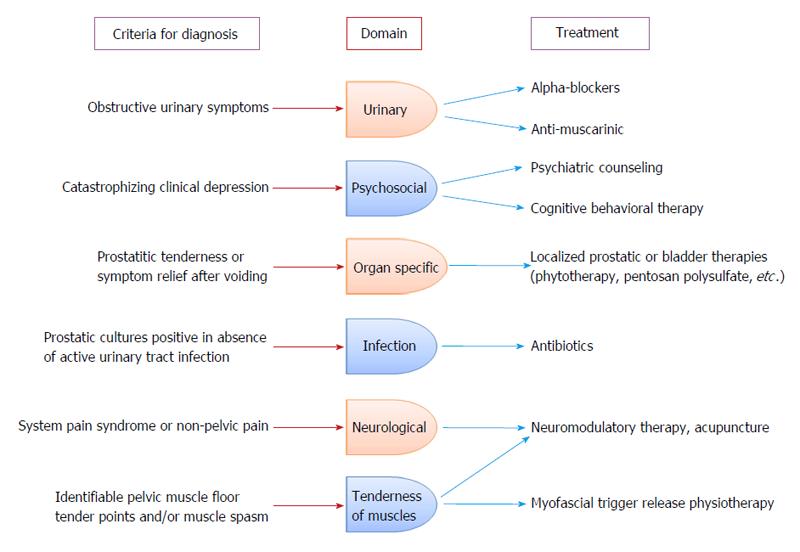

A more tailored treatment approach was required to treat this condition with varied symptomatology and consequently Shoskes et al[137] and Nickel et al[138] came up with a phenotypic approach for the management of CP/CPPS. The UPOINT phenotypic approach comprises of six clinical domains including Urinary symptoms, Psychosocial dysfunction, Organ specific findings, Infection, Neurologic dysfunction and Tenderness of muscles[136]. Recently sexual dysfunction was included in this phenotypic approach, which led to the modified UPOINTS system after a study showed sexual dysfunction domain correlated with the NIH-CPSI score significantly[139,140].

To test the treatment efficacy of the UPOINT system, a prospective study was conducted, including 100 patients treated with multimodal therapy. Men were re-evaluated after 26 wk. The treatment proved to be effective and almost 86% patients experienced at least a 6-point decrease in NIH-CPSI score and total improvement in NIH-CPSI scores were from 25.2 ± 6.1 to 13.2 ± 7.2 (P < 0.0001). These results are comparable to some of the large monotherapy trials[141].

An algorithm has been constructed to provide individualized therapy based on the phenotypes within the UPOINT system (Figure 3). Because of the fact that monotherapies give modest therapeutic outcomes, a multimodal treatment approach would be considered more rational and should be considered as a primary recommendation based on patients phenotype.

CP/CPPS has been baffling the physicians since long because of its complex etiology and difficult-to-treat nature. No single etiological factor has been linked strongly to CP/CPPS, instead a cluster of factors cause symptoms in CP/CPPS patients. This relates to the fact that monotherapy does not always proves effective in treating the symptoms. Primary role of the Urologist is to rule out differentials that present with similar symptoms as CP/CPPS and utilize diagnostic modalities that cause minimum physical and psychological distress to the patients and provide most accurate results. Multimodal therapy such as UPOINT has been beneficial because of its role in influencing multiple constituents that lead to CP/CPPS. Overall CP/CPPS should not be considered as a localized pathology and a centralized approach is recommended to reverse or halt the progression of symptoms. There is still space for development of novel therapeutic regimens including the development of a vaccine that can be offered to CP/CPPS patients. Psychological stress should always be ruled out and psychiatric counseling needs to be offered along with pharmacological treatment. Pelvic floor biofeedback along with acupuncture proved to help patients but larger multicenter studies are still required to prove its effectiveness in CP/CPPS patients. It is recommended that physicians keep in touch with new researches and treatments coming out for CP/CPPS, in order to provide their patients a chance for an up to date and improved treatment opportunities. For now the best available strategy would be to individually tailor treatment plan for each patient.

P- Reviewer: Engelhardt PF S- Editor: Gong XM L- Editor: A E- Editor: Liu SQ

| 1. | Pontari MA, Joyce GF, Wise M, McNaughton-Collins M. Prostatitis. J Urol. 2007;177:2050-2057. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Collins MM, Stafford RS, O’Leary MP, Barry MJ. How common is prostatitis? A national survey of physician visits. J Urol. 1998;159:1224-1228. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 446] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 375] [Article Influence: 14.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Schaeffer AJ, Landis JR, Knauss JS, Propert KJ, Alexander RB, Litwin MS, Nickel JC, O’Leary MP, Nadler RB, Pontari MA. Demographic and clinical characteristics of men with chronic prostatitis: the national institutes of health chronic prostatitis cohort study. J Urol. 2002;168:593-598. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 157] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Schaeffer AJ. Clinical practice. Chronic prostatitis and the chronic pelvic pain syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:1690-1698. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 155] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 159] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Nickel JC. Prostatitis. Can Urol Assoc J. 2011;5:306-315. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Krieger JN, Egan KJ, Ross SO, Jacobs R, Berger RE. Chronic pelvic pains represent the most prominent urogenital symptoms of “chronic prostatitis”. Urology. 1996;48:715-721; discussion 721-722. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 166] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 172] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | de la Rosette JJ, Hubregtse MR, Meuleman EJ, Stolk-Engelaar MV, Debruyne FM. Diagnosis and treatment of 409 patients with prostatitis syndromes. Urology. 1993;41:301-307. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 118] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nickel JC, Nyberg LM, Hennenfent M. Research guidelines for chronic prostatitis: consensus report from the first National Institutes of Health International Prostatitis Collaborative Network. Urology. 1999;54:229-233. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 199] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 208] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Litwin MS, McNaughton-Collins M, Fowler FJ, Nickel JC, Calhoun EA, Pontari MA, Alexander RB, Farrar JT, O’Leary MP. The National Institutes of Health chronic prostatitis symptom index: development and validation of a new outcome measure. Chronic Prostatitis Collaborative Research Network. J Urol. 1999;162:369-375. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 620] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 586] [Article Influence: 23.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Nickel JC, Alexander RB, Schaeffer AJ, Landis JR, Knauss JS, Propert KJ. Leukocytes and bacteria in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome compared to asymptomatic controls. J Urol. 2003;170:818-822. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 167] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Pontari MA. Etiology of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: psychoimmunoneurendocrine dysfunction (PINE syndrome) or just a really bad infection? World J Urol. 2013;31:725-732. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Krieger JN, Nyberg L, Nickel JC. NIH consensus definition and classification of prostatitis. JAMA. 1999;282:236-237. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 974] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 853] [Article Influence: 34.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nickel JC. The Pre and Post Massage Test (PPMT): a simple screen for prostatitis. Tech Urol. 1997;3:38-43. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 14. | Potts JM, Payne CK. Urologic chronic pelvic pain. Pain. 2012;153:755-758. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 24] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Potts J, Payne RE. Prostatitis: Infection, neuromuscular disorder, or pain syndrome? Proper patient classification is key. Cleve Clin J Med. 2007;74 Suppl 3:S63-S71. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 33] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Weidner W, Schiefer HG, Krauss H, Jantos C, Friedrich HJ, Altmannsberger M. Chronic prostatitis: a thorough search for etiologically involved microorganisms in 1,461 patients. Infection. 1991;19 Suppl 3:S119-S125. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 174] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Hua VN, Williams DH, Schaeffer AJ. Role of bacteria in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Curr Urol Rep. 2005;6:300-306. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Krieger JN, Riley DE. Bacteria in the chronic prostatitis-chronic pelvic pain syndrome: molecular approaches to critical research questions. J Urol. 2002;167:2574-2583. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Hochreiter WW, Duncan JL, Schaeffer AJ. Evaluation of the bacterial flora of the prostate using a 16S rRNA gene based polymerase chain reaction. J Urol. 2000;163:127-130. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 105] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Karatas OF, Turkay C, Bayrak O, Cimentepe E, Unal D. Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence in patients with chronic prostatitis: a pilot study. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 2010;44:91-94. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 14] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rudick CN, Berry RE, Johnson JR, Johnston B, Klumpp DJ, Schaeffer AJ, Thumbikat P. Uropathogenic Escherichia coli induces chronic pelvic pain. Infect Immun. 2011;79:628-635. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kouiavskaia DV, Southwood S, Berard CA, Klyushnenkova EN, Alexander RB. T-cell recognition of prostatic peptides in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2009;182:2483-2489. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 27] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ren S, Sakai K, Schwartz LB. Regulation of human mast cell beta-tryptase: conversion of inactive monomer to active tetramer at acid pH. J Immunol. 1998;160:4561-4569. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 24. | Kalesnikoff J, Galli SJ. New developments in mast cell biology. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1215-1223. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 519] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 547] [Article Influence: 34.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Done JD, Rudick CN, Quick ML, Schaeffer AJ, Thumbikat P. Role of mast cells in male chronic pelvic pain. J Urol. 2012;187:1473-1482. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 57] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Roman K, Done JD, Schaeffer AJ, Murphy SF, Thumbikat P. Tryptase-PAR2 axis in experimental autoimmune prostatitis, a model for chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Pain. 2014;155:1328-1338. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Quick ML, Wong L, Mukherjee S, Done JD, Schaeffer AJ, Thumbikat P. Th1-Th17 cells contribute to the development of uropathogenic Escherichia coli-induced chronic pelvic pain. PLoS One. 2013;8:e60987. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Breser ML, Motrich RD, Sanchez LR, Mackern-Oberti JP, Rivero VE. Expression of CXCR3 on specific T cells is essential for homing to the prostate gland in an experimental model of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Immunol. 2013;190:3121-3133. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 39] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Murphy SF, Schaeffer AJ, Thumbikat P. Immune mediators of chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Nat Rev Urol. 2014;11:259-269. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 64] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Thumbikat P, Shahrara S, Sobkoviak R, Done J, Pope RM, Schaeffer AJ. Prostate secretions from men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome inhibit proinflammatory mediators. J Urol. 2010;184:1536-1542. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 15] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Shahed AR, Shoskes DA. Correlation of beta-endorphin and prostaglandin E2 levels in prostatic fluid of patients with chronic prostatitis with diagnosis and treatment response. J Urol. 2001;166:1738-1741. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 61] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Pontari MA, Ruggieri MR. Mechanisms in prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2008;179:S61-S67. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 96] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Miller LJ, Fischer KA, Goralnick SJ, Litt M, Burleson JA, Albertsen P, Kreutzer DL. Nerve growth factor and chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2002;59:603-608. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 122] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Mazurek N, Weskamp G, Erne P, Otten U. Nerve growth factor induces mast cell degranulation without changing intracellular calcium levels. FEBS Lett. 1986;198:315-320. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 111] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Yilmaz U, Liu YW, Berger RE, Yang CC. Autonomic nervous system changes in men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2007;177:2170-2174; discussion 2174. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 36] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Cho DS, Choi JB, Kim YS, Joo KJ, Kim SH, Kim JC, Kim HW. Heart rate variability in assessment of autonomic dysfunction in patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2011;78:1369-1372. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Shen X, Ming A, Li X, Zhou Z, Song B. Nanobacteria: a possible etiology for type III prostatitis. J Urol. 2010;184:364-369. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Shoskes DA, Thomas KD, Gomez E. Anti-nanobacterial therapy for men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome and prostatic stones: preliminary experience. J Urol. 2005;173:474-477. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Nickel JC. Treatment of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31 Suppl 1:S112-S116. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 37] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kaplan SA, Ikeguchi EF, Santarosa RP, D’Alisera PM, Hendricks J, Te AE, Miller MI. Etiology of voiding dysfunction in men less than 50 years of age. Urology. 1996;47:836-839. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 113] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | He W, Chen M, Zu X, Li Y, Ning K, Qi L. Chronic prostatitis presenting with dysfunctional voiding and effects of pelvic floor biofeedback treatment. BJU Int. 2010;105:975-977. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 19] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kaplan SA, Santarosa RP, D’Alisera PM, Fay BJ, Ikeguchi EF, Hendricks J, Klein L, Te AE. Pseudodyssynergia (contraction of the external sphincter during voiding) misdiagnosed as chronic nonbacterial prostatitis and the role of biofeedback as a therapeutic option. J Urol. 1997;157:2234-2237. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 87] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Li Y, Qi L, Wen JG, Zu XB, Chen ZY. Chronic prostatitis during puberty. BJU Int. 2006;98:818-821. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Mehik A, Hellström P, Lukkarinen O, Sarpola A, Alfthan O. Increased intraprostatic pressure in patients with chronic prostatitis. Urol Res. 1999;27:277-279. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 21] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Mehik A, Hellström P, Nickel JC, Kilponen A, Leskinen M, Sarpola A, Lukkarinen O. The chronic prostatitis-chronic pelvic pain syndrome can be characterized by prostatic tissue pressure measurements. J Urol. 2002;167:137-140. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 29] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Shoskes DA, Berger R, Elmi A, Landis JR, Propert KJ, Zeitlin S. Muscle tenderness in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: the chronic prostatitis cohort study. J Urol. 2008;179:556-560. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Anderson RU, Sawyer T, Wise D, Morey A, Nathanson BH. Painful myofascial trigger points and pain sites in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Urol. 2009;182:2753-2758. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 75] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Daniels NA, Link CL, Barry MJ, McKinlay JB. Association between past urinary tract infections and current symptoms suggestive of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. J Natl Med Assoc. 2007;99:509-516. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 49. | Collins MM, Meigs JB, Barry MJ, Walker Corkery E, Giovannucci E, Kawachi I. Prevalence and correlates of prostatitis in the health professionals follow-up study cohort. J Urol. 2002;167:1363-1366. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 50. | Murphy AB, Macejko A, Taylor A, Nadler RB. Chronic prostatitis: management strategies. Drugs. 2009;69:71-84. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Luzzi GA. Chronic prostatitis and chronic pelvic pain in men: aetiology, diagnosis and management. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2002;16:253-256. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Tran CN, Shoskes DA. Sexual dysfunction in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. World J Urol. 2013;31:741-746. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 46] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | McNaughton Collins M, MacDonald R, Wilt TJ. Diagnosis and treatment of chronic abacterial prostatitis: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2000;133:367-381. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 114] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Sharp VJ, Takacs EB, Powell CR. Prostatitis: diagnosis and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2010;82:397-406. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 55. | Nickel JC. Clinical evaluation of the man with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2002;60:20-22; discussion 22-23. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 43] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Schaeffer AJ. Epidemiology and evaluation of chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2008;31 Suppl 1:S108-S111. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 45] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Meares EM, Stamey TA. Bacteriologic localization patterns in bacterial prostatitis and urethritis. Invest Urol. 1968;5:492-518. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 58. | Habermacher GM, Chason JT, Schaeffer AJ. Prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:195-206. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 102] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Nickel JC, Shoskes D, Wang Y, Alexander RB, Fowler JE, Zeitlin S, O’Leary MP, Pontari MA, Schaeffer AJ, Landis JR. How does the pre-massage and post-massage 2-glass test compare to the Meares-Stamey 4-glass test in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome? J Urol. 2006;176:119-124. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 119] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Morote J, Lopez M, Encabo G, de Torres IM. Effect of inflammation and benign prostatic enlargement on total and percent free serum prostatic specific antigen. Eur Urol. 2000;37:537-540. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 85] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Nadler RB, Collins MM, Propert KJ, Mikolajczyk SD, Knauss JS, Landis JR, Fowler JE, Schaeffer AJ, Alexander RB. Prostate-specific antigen test in diagnostic evaluation of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2006;67:337-342. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 54] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Watanabe T, Inoue M, Sasaki K, Araki M, Uehara S, Monden K, Saika T, Nasu Y, Kumon H, Chancellor MB. Nerve growth factor level in the prostatic fluid of patients with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome is correlated with symptom severity and response to treatment. BJU Int. 2011;108:248-251. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 49] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Davis SN, Morin M, Binik YM, Khalife S, Carrier S. Use of pelvic floor ultrasound to assess pelvic floor muscle function in Urological Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome in men. J Sex Med. 2011;8:3173-3180. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 35] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Alexander RB, Propert KJ, Schaeffer AJ, Landis JR, Nickel JC, O’Leary MP, Pontari MA, McNaughton-Collins M, Shoskes DA, Comiter CV. Ciprofloxacin or tamsulosin in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a randomized, double-blind trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141:581-589. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 201] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 204] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Nickel JC, Downey J, Clark J, Casey RW, Pommerville PJ, Barkin J, Steinhoff G, Brock G, Patrick AB, Flax S. Levofloxacin for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in men: a randomized placebo-controlled multicenter trial. Urology. 2003;62:614-617. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 137] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Nickel JC, Downey J, Johnston B, Clark J. Predictors of patient response to antibiotic therapy for the chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a prospective multicenter clinical trial. J Urol. 2001;165:1539-1544. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 107] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Choe HS, Lee SJ, Han CH, Shim BS, Cho YH. Clinical efficacy of roxithromycin in men with chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome in comparison with ciprofloxacin and aceclofenac: a prospective, randomized, multicenter pilot trial. J Infect Chemother. 2014;20:20-25. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Fowler JE. Antimicrobial therapy for bacterial and nonbacterial prostatitis. Urology. 2002;60:24-26; discussion 26. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 18] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Zhou Z, Hong L, Shen X, Rao X, Jin X, Lu G, Li L, Xiong E, Li W, Zhang J. Detection of nanobacteria infection in type III prostatitis. Urology. 2008;71:1091-1095. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 63] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Goldmeier D, Madden P, McKenna M, Tamm N. Treatment of category III A prostatitis with zafirlukast: a randomized controlled feasibility study. Int J STD AIDS. 2005;16:196-200. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 30] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Nickel JC, Pontari M, Moon T, Gittelman M, Malek G, Farrington J, Pearson J, Krupa D, Bach M, Drisko J. A randomized, placebo controlled, multicenter study to evaluate the safety and efficacy of rofecoxib in the treatment of chronic nonbacterial prostatitis. J Urol. 2003;169:1401-1405. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 116] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Thakkinstian A, Attia J, Anothaisintawee T, Nickel JC. α-blockers, antibiotics and anti-inflammatories have a role in the management of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. BJU Int. 2012;110:1014-1022. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 70] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Tuğcu V, Taşçi AI, Fazlioğlu A, Gürbüz G, Ozbek E, Sahin S, Kurtuluş F, Cek M. A placebo-controlled comparison of the efficiency of triple- and monotherapy in category III B chronic pelvic pain syndrome (CPPS). Eur Urol. 2007;51:1113-1117; discussion 1118. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 72] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Zhao WP, Zhang ZG, Li XD, Yu D, Rui XF, Li GH, Ding GQ. Celecoxib reduces symptoms in men with difficult chronic pelvic pain syndrome (Category IIIA). Braz J Med Biol Res. 2009;42:963-967. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 38] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Murphy AB, Nadler RB. Pharmacotherapy strategies in chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome management. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2010;11:1255-1261. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 17] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Nickel JC, Forrest JB, Tomera K, Hernandez-Graulau J, Moon TD, Schaeffer AJ, Krieger JN, Zeitlin SI, Evans RJ, Lama DJ. Pentosan polysulfate sodium therapy for men with chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a multicenter, randomized, placebo controlled study. J Urol. 2005;173:1252-1255. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 87] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Nickel JC, Atkinson G, Krieger JN, Mills IW, Pontari M, Shoskes DA, Crook TJ. Preliminary assessment of safety and efficacy in proof-of-concept, randomized clinical trial of tanezumab for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome. Urology. 2012;80:1105-1110. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 44] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Nickel JC, Touma N. α-Blockers for the Treatment of Chronic Prostatitis/Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: An Update on Current Clinical Evidence. Rev Urol. 2012;14:56-64. [PubMed] [Cited in This Article: ] |

| 79. | Mehik A, Alas P, Nickel JC, Sarpola A, Helström PJ. Alfuzosin treatment for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, pilot study. Urology. 2003;62:425-429. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 125] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Nickel JC, Krieger JN, McNaughton-Collins M, Anderson RU, Pontari M, Shoskes DA, Litwin MS, Alexander RB, White PC, Berger R. Alfuzosin and symptoms of chronic prostatitis-chronic pelvic pain syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:2663-2673. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 139] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 145] [Article Influence: 9.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Nickel JC, Narayan P, McKay J, Doyle C. Treatment of chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome with tamsulosin: a randomized double blind trial. J Urol. 2004;171:1594-1597. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 133] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Cheah PY, Liong ML, Yuen KH, Teh CL, Khor T, Yang JR, Yap HW, Krieger JN. Terazosin therapy for chronic prostatitis/chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a randomized, placebo controlled trial. J Urol. 2003;169:592-596. [PubMed] [DOI] [Cited in This Article: ] [Cited by in F6Publishing: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |