Dihalogen and Pnictogen Bonding in Crystalline Icosahedral Phosphaboranes

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results and Discussion

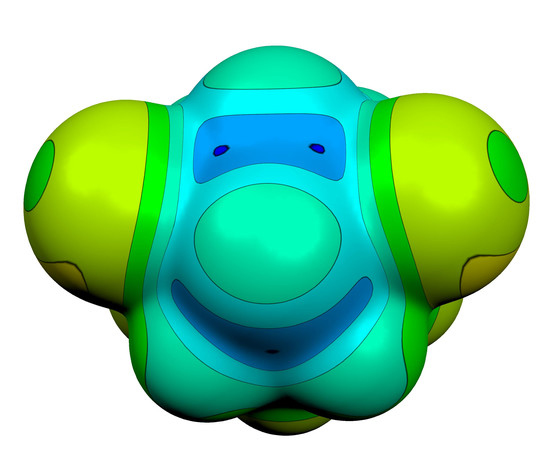

3.1. The Properties of Isolated Molecules

3.2. Interactions in the Single Crystal of 1 and the Crystal of 2•Toluene

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grüner, B.; Hnyk, D.; Císařová, I.; Plzák, Z.; Štíbr, B. Phosphaborane Chemistry. Syntheses and Calculated Molecular Structures of Mono- and Di-chloro Derivatives of 1,2-Diphospha-closo-dodecaborane(10). J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 2002, 15, 2954–2959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Štíbr, B.; Holub, J.; Bakardjiev, M.; Hnyk, D.; Tok, O.L.; Milius, W.; Wrackmeyer, B. Phosphacarborane Chemistry: The Synthesis of the Parent Phosphadicarbaboranes nido-7,8,9-PC2B8H11 and [nido-7,8,9-PC2B8H10]−, and Their 10-Cl Derivatives—Analogs of the Cyclopentadiene Anion. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2002, 9, 2320–2326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, J.L.; Whitesell, M.A.; Chapman, R.W.; Kester, J.G.; Huffman, J.C.; Todd, L.J. Synthesis of Some 10-, 11-, and 12-Atom Phosphaboranes. Crystal Structure of 2-(Trimethylamine)-1-PB11H10. Inorg. Chem. 1993, 32, 3369–3372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, W.; Sawitzki, G.; Haubold, W. Synthesis of Halogenated Polyhedral Phosphaboranes. Crystal Structures of closo-1,7-P2B10Cl10. Inorg. Chem. 2000, 39, 1282–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Melichar, P.; Hnyk, D.; Fanfrlík, J. Systematic Examination of Classical and Multi-Center Bonding in Heteroborane Clusters. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 4666–4675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hnyk, D.; Všetečka, V.; Drož, L.; Exner, O. Charge Distribution within 1,2-Dicarba-closo-dodecaborane: Dipole Moments of its Phenyl Derivatives. Collect. Czech. Chem. Commun. 2001, 66, 1375–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.; Hennemann, M.; Murray, J.S.; Politzer, P. Halogen Bonding: The σ-Hole. J. Mol. Model. 2007, 13, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pecina, A.; Lepšík, M.; Hnyk, D.; Hobza, P.; Fanfrlík, J. Chalcogen and Pnicogen Bonds in Complexes of Neutral Icosahedral and Biccaped Square-Antiprismatic Heteroboranes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2015, 119, 1388–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanfrlík, J.; Přáda, A.; Padělková, Z.; Pecina, A.; Macháček, J.; Lepšík, M.; Holub, J.; Růžička, A.; Hnyk, D.; Hobza, P. The Dominant Role of Chalcogen Bonding in the Crystal Packing of 2D/3D Aromatics. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 10139–10142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanfrlík, J.; Hnyk, D. Chalcogens Act as Inner and Outer Heteroatoms in Borane Cages with Possible Consequences for σ-Hole Interactions. CrystEngComm 2016, 47, 8973–9162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanfrlík, J.; Holub, J.; Růžičková, Z.; Řezáč, J.; Lane, P.D.; Wann, D.A.; Hnyk, D.; Růžička, A.; Hobza, P. Competition between Halogen, Hydrogen and Dihydrogen Bonding in Brominated Carboranes. ChemPhysChem 2016, 17, 3373–3376. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Holub, J.; Melichar, P.; Růžičková, Z.; Vrána, J.; Wann, D.A.; Fanfrlík, J.; Hnyk, D.; Růžička, A. A Novel Stibacarbaborane Cluster with Adjacent Antimony Atoms Exhibiting Unique Pnictogen Bond Formation that Dominates Its Crystal Packing. Dalton Trans. 2017, 46, 13714–13719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holub, J.; Růžičková, Z.; Hobza, P.; Fanfrlík, J.; Hnyk, D.; Růžička, A. Various Types of Non-covalent Interactions Contributing Towards Crystal Packing of Halogenated Diphospha-dicarborane with an Open Pentagonal Belt. New J. Chem. 2018, 42, 10481–10483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Mennucci, B.; Petersson, G.A.; et al. Gaussian 09, Revision, D.01; Gaussian, Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Flűkiger, P.; Lűthi, H.P.; Portmann, S.; Weber, J. MOLEKEL 4.3; Swiss Center for Scientific Computing: Manno, Switzerland, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Portmann, S.; Luthi, H.P. MOLEKEL: An Interactive Molecular Graphic Tool. CHIMIA Int. J. Chem. 2000, 54, 766–770. [Google Scholar]

- Riley, K.E.; Tran, K.A.; Lane, P.; Murray, J.S.; Politzer, P. Comparative Analysis of Electrostatic Potential Maxima and Minima on Molecular Surfaces, as Determined by Three Methods and a Variety of Basis Sets. J. Comput. Sci. 2016, 17, 273–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hostaš, J.; Řezáč, J. Accurate DFT-D3 Calculations in a Small Basis Set. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017, 13, 3575–3585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Řezáč, J.; Hobza, P. Advanced Corrections of Hydrogen Bonding and Dispersion for Semiempirical Quantum Mechanical Methods. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2012, 8, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Řezáč, J.; Huang, Y.; Hobza, P.; Beran, J.O.G. Benchmark Calculations of Three-Body Intermolecular Interactions and the Performance of Low-Cost Electronic Structure Methods. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015, 11, 3065–3079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitonak, M.; Neogady, P.; Cerny, J.; Grimme, S.; Hobza, P. Scaled MP3 Non-Covalent Interaction Energies Agree Closely with Accurate CCSD(T) Benchmark Data. ChemPhysChem 2009, 10, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halkier, A.; Helgaker, T.; Jørgensen, P.; Klopper, W.; Koch, H.; Olsen, J.; Wilson, A.K. Basis-Set Convergence in Correlated Calculations on Ne, N2, and H2O. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998, 286, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeziorski, B.; Moszynski, R.; Szalewicz, K. Perturbation Theory Approach to Intermolecular Potential Energy Surfaces of van der Waals Complexes. Chem. Rev. 1994, 94, 1887–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, T.M.; Burns, L.A.; Parrish, R.M.; Ryno, A.G.; Sherrill, C.D. Levels of Symmetry Adapted Perturbation Theory (SAPT). I. Efficiency and Performance for Interaction Energies. J. Chem. Phys. 2014, 140, 094106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahlrichs, R.; Bar, M.; Haser, M.; Horn, H.; Kolmel, C. Electronic Structure Calculations on Workstation Computers: The Program System Turbomole. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1989, 162, 165–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turney, J.M.; Simmonett, A.C.; Parrish, R.M.; Hohenstein, E.G.; Evangelista, F.; Fermann, J.T.; Mintz, B.J.; Burns, L.A.; Wilke, J.J.; Abrams, M.L.; et al. Psi4: An Open-Source Ab Initio Electronic Structure Program. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2012, 2, 556–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stewart, J.P. Optimization of parameters for semiempirical methods IV: Extension of MNDO, AM1, and PM3 to more main group elements. J. Mol. Model. 2004, 10, 155–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Řezáč, J. Cuby: An Integrative Framework for Computational Chemistry. J. Comput. Chem. 2016, 37, 1230–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Macháček, J.; Plešek, J.; Holub, J.; Hnyk, D.; Všetečka, V.; Císařová, I.; Kaupp, M.; Štíbr, B. New Route to 1-Thia-closo-dodecaborane(11), closo-1-SB11H11, and Its Halogenation Reactions. The Effect of the Halogen on the Dipole Moments and the NMR Spectra and the Importance of Spin-Orbit Coupling for the 11B Chemical Shifts. Dalton Trans. 2006, 1024–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Mantina, M.; Chamberlin, A.C.; Valero, R.; Cramer, C.J.; Truhlar, D.G. Consistent van der Waals Radii for the Whole Main Group. J. Phys. Chem. A 2009, 113, 5806–5812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schmidbaur, H.; Nowak, R.; Steigelmann, O.; Muller, G. π-Complexes of p-Block Elements: Synthesis and Structures of Adducts of Arsenic and Antimony Halides with Alkylated Benzenes. Chemische Berichte 1990, 123, 1221–1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burford, N.; Clyburne, J.A.C.; Wiles, J.A.; Cameron, T.S.; Robertson, K.N. Tethered Diarenes as Four-Site Donors to SbCl3. Organometallics 1996, 15, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burford, N.; Clyburne, J.A.C.; Bakshi, P.K.; Cameron, T.S. η6-Arene Complexation to a Phosphenium Cation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 8829–8830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGrath, T.D.; Welch, A.J. Steric Effects in Heteroboranes. IV. 1-Ph-2-Br-1,2-closo-C2B10H10. Acta Cryst. 1995, C51, 649–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauzá, A.; Quiñonero, D.; Deyà, P.M.; Frontera, A. Halogen Bonding versus Chalcogen and Pnicogen Bonding: A Combined Cambridge Structural Database and Theoretical Study. CrystEngComm 2013, 15, 3137–3144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awwadi, F.F.; Willet, R.D.; Peterson, K.A.; Twamley, B. The Nature of Halogen···Halogen Synthons: Crystalographic and Theoretical Studies. Chem. Eur. J. 2006, 12, 8952–8960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Compound | Atom | VS,max [kcal mol−1] |

|---|---|---|

| 3,6-Cl2-closo-1,2-P2B10H8 (1) | P(1,2) | 2 × 25.2; 25.1 |

| Cl(3,6) 1 | 2.3 | |

| closo-1,7-P2B10Cl10 (2) | P(1,7) | 30.2; 2 × 28.9; 2 × 27.8 |

| Cl(2,3) | 13.1 | |

| Cl(9,10) 2 | 1.5 |

| Interaction | DFT-D3/MP2.5 | SAPT0/jun-cc-pVDZ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Eelec | Eind | Edisp | Eexch | ||

| A···B | −4.85/−4.23 | −4.83 | −2.28 (21%) | −0.81 (8%) | −7.67 (71%) | 5.94 |

| A···C | −4.09/−3.90 | −4.01 | −2.26 (27%) | −0.61 (7%) | −5.42 (65%) | 4.28 |

| A···D | −3.85/−3.35 | −3.70 | −2.11 (24%) | −0.65 (8%) | −5.87 (68%) | 4.92 |

| Interaction | DFT-D3/MP2.5 | SAPT0/jun-cc-pVDZ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Eelec | Eind | Edisp | Eexch | ||

| 2···toluene Pn-bond | −9.94/−10.55 | −11.56 | −9.80 (35%) | −3.96 (14%) | −14.61 (52%) | 16.81 |

| 2···toluene stacking | −2.51/−2.25 | −1.96 | −0.84 (22%) | −0.21 (6%) | −2.75 (72%) | 1.84 |

| 2···toluene H-bond | −0.87/−0.80 | −0.51 | −0.35 (16 %) | −0.21 (10%) | −1.58 (74%) | 1.63 |

| 2···2 bifurcated diX-bonds | −3.67 | −3.27 | −1.17 (16%) | −0.32 (4%) | −5.73 (79%) | 3.95 |

| 2···2 bifurcated diX-bond | −2.94 | −3.01 | −1.78 (26%) | −0.40 (6%) | −4.67 (68%) | 3.84 |

| 2···2 diX-bond | −2.32/−2.65 | −2.13 | −1.51 (25%) | −0.35 (6%) | −4.13 (69%) | 3.86 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fanfrlík, J.; Hnyk, D. Dihalogen and Pnictogen Bonding in Crystalline Icosahedral Phosphaboranes. Crystals 2018, 8, 390. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/cryst8100390

Fanfrlík J, Hnyk D. Dihalogen and Pnictogen Bonding in Crystalline Icosahedral Phosphaboranes. Crystals. 2018; 8(10):390. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/cryst8100390

Chicago/Turabian StyleFanfrlík, Jindřich, and Drahomír Hnyk. 2018. "Dihalogen and Pnictogen Bonding in Crystalline Icosahedral Phosphaboranes" Crystals 8, no. 10: 390. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/cryst8100390