New Liquid Chemical Hydrogen Storage Technology

Abstract

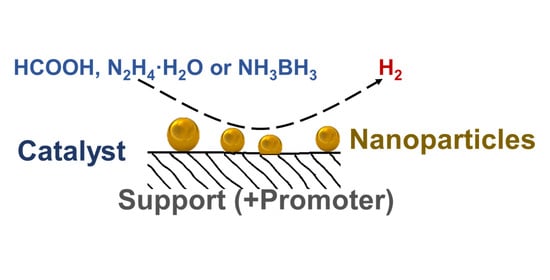

:1. Introduction

2. Formic Acid Dehydrogenation

2.1. Monometallic Catalysts

2.2. Bimetallic and Multimetallic Catalysts

3. Hydrazine Hydrate Dehydrogenation

3.1. Monometallic Catalysts

3.2. Bimetallic Catalysts

4. Ammonia Borane Dehydrogenation

4.1. Hydrolysis of Ammonia Borane

4.1.1. Monometallic Catalysts

4.1.2. Bimetallic Catalysts

4.2. Methanolysis of Ammonia Borane

5. Conclusions and Outlook

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Majumdar, A.; Deutch, J.M.; Prasher, R.S.; Griffin, T.P. A framework for a hydrogen economy. Joule 2021, 5, 1905–1908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.; Zhang, T.; Zhou, D.; Sun, P.; Lu, Z.; Bian, H.; Dang, J.; Gao, H.; Qian, Y.; Li, W.; et al. Charge Transfer of Interfacial Catalysts for Hydrogen Energy. ACS Mater. Lett. 2022, 4, 967–977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Li, Y.; Li, Y. Hydrogen Storage and Transportation; Chemical Industry Press Co., Ltd.: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Kirlikovali, K.O.; Idrees, K.B.; Wasson, M.C.; Farha, O.K. Porous Materials for Hydrogen Storage. Chem 2022, 8, 693–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onishi, N.; Laurenczy, G.; Beller, M.; Himeda, Y. Recent progress for reversible homogeneous catalytic hydrogen storage in formic acid and in methanol. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 373, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, C.; Jia, Y.; Yao, X. Recent advances in liquid-phase chemical hydrogen storage. Energy Storage Mater. 2020, 26, 290–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xu, Q. Gold-containing metal nanoparticles for catalytic hydrogen generation from liquid chemical hydrides. Chin. J. Catal. 2016, 37, 1594–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onishi, N.; Iguchi, M.; Yang, X.; Kanega, R.; Kawanami, H.; Xu, Q.; Himeda, Y. Development of effective catalysts for hydrogen storage technology using formic acid. Adv. Energy Mater. 2019, 9, 1801275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xu, Q. Encapsulating metal nanocatalysts within porous organic hosts. Trends Chem. 2020, 2, 214–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Astruc, D. Recent developments of nanocatalyzed liquid-phase hydrogen generation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2021, 50, 3437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Zhou, H.; Wang, C.G.; Ye, E.; Xu, J.W.; Loh, X.J.; Li, Z. Current research progress and perspectives on liquid hydrogen rich molecules in sustainable hydrogen storage. Energy Storage Mater. 2021, 35, 695–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, R.; Lu, W.; Toan, S.; Zhou, Z.; Russell, C.K.; Sun, Z.; Sun, Z. Thermocatalytic formic acid dehydrogenation: Recent advances and emerging trends. J. Mater. Chem. A 2021, 9, 24241–24260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulushev, D.A.; Ross, J.R.H. Heterogeneous catalysts for hydrogenation of CO2 and bicarbonates to formic acid and formates. Catal. Rev. 2018, 60, 566–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Xue, W.; Wang, Y.J. Review on heterogeneous catalysts for hydrogen generation via liquid-phase formic acid decomposition. J. Chem. Eng. Chin. Univ. 2019, 33, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Yadav, M.; Akita, T.; Tsumori, N.; Xu, Q. Strong metal–molecular support interaction (SMMSI): Amine-functionalized gold nanoparticles encapsulated in silica nanospheres highly active for catalytic decomposition of formic acid. J. Mater. Chem. 2012, 22, 12582–12586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Q.Y.; Du, X.L.; Liu, Y.M.; Cao, Y.; He, H.Y.; Fan, K.N. Efficient subnanometric gold-catalyzed hydrogen generation via formic acid decomposition under ambient conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 8926–8933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.Q.; Yang, X.F.; Huang, Y.Q.; Xu, S.T.; Su, X.L.; Pan, X.; Xu, J.M.; Wang, A.Q.; Liang, C.H.; Wang, X.K.; et al. A Schiff base modified gold catalyst for green and efficient H2 production from formic acid. Energy Environ. Sci. 2015, 8, 3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zacharska, M.; Chuvilin, A.L.; Kriventsov, V.V.; Beloshapkin, S.; Estrada, M.; Simakov, A.; Bulushev, D.A. Support effect for nanosized Au catalysts in hydrogen production from formic acid decomposition. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2016, 6, 6853–6860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulushev, D.A.; Zacharska, M.; Guo, Y.; Beloshapkin, S.; Simakov, A. CO-free hydrogen production from decomposition of formic acid over Au/Al2O3 catalysts doped with potassium ions. Catal. Commun. 2017, 92, 86–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulushev, D.A.; Chekhova, G.N.; Sobolev, V.I.; Chuvilin, A.L.; Fedoseeva, Y.V.; Gerasko, O.A.; Okotrub, A.V.; Bulusheva, L.G. Cucurbit [6] uril as a co-catalyst for hydrogen production from formic acid. Mater. Today Energy 2022, 26, 100998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Sun, Q.; Bai, R.; Li, X.; Guo, G.; Yu, J. In situ confinement of ultrasmall Pd clusters within nanosized silicalite-1 zeolite for highly efficient catalysis of hydrogen generation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138, 7484–7487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Wang, N.; Bing, Q.; Si, R.; Liu, J.; Bai, R.; Zhang, P.; Jia, M.; Yu, J. Subnanometric hybrid Pd-M(OH)2, M = Ni, Co, clusters in zeolites as highly efficient nanocatalysts for hydrogen generation. Chem 2017, 3, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhu, Q.L.; Tsumori, N.; Xu, Q. Sodium hydroxide-assisted growth of uniform Pd nanoparticles on nanoporous carbon MSC-30 for efficient and complete dehydrogenation of formic acid under ambient conditions. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.L.; Tsumori, N.; Xu, Q. Immobilizing extremely catalytically active palladium nanoparticles to carbon nanospheres: A weakly-capping growth approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 11743–11748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, F.Z.; Zhu, Q.L.; Tsumori, N.; Xu, Q. Diamine-alkalized reduced graphene oxide: Immobilization of sub-2 nm palladium nanoparticles and optimization of catalytic activity for dehydrogenation of formic acid. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 5141–5144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yang, X.; Tsumori, N.; Liu, Z.; Himeda, Y.; Autrey, T.; Xu, Q. Tandem nitrogen functionalization of porous carbon: Toward immobilizing highly active palladium nanoclusters for dehydrogenation of formic acid. ACS Catal. 2017, 7, 2720–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Yang, X.; Chen, L.; Tsumori, N.; Taguchi, N.; Xu, Q. Interfacing with Fe–N–C sites boosts the formic acid dehydrogenation of palladium nanoparticles. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13, 46749–46755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Q.Y.; Lin, J.D.; Liu, Y.M.; Du, X.L.; Wang, J.Q.; He, H.Y.; Cao, Y. An aqueous rechargeable formate-based hydrogen battery driven by heterogenous Pd catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 13583–13587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, Q.Y.; Lin, J.D.; Liu, Y.M.; He, H.Y.; Huang, F.Q.; Cao, Y. Dehydrogenation of formic acid at room temperature: Boosting palladium nanoparticle efficiency by coupling with pyridinic-nitrogen-doped carbon. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 11849–11853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulushev, D.A.; Zacharska, M.; Shlyakhova, E.V.; Chuvilin, A.L.; Guo, Y.; Beloshapkin, S.; Okotrub, A.V.; Bulusheva, L.G. Single isolated Pd2+ cations supported on N-doped carbon as active sites for hydrogen production from formic acid decomposition. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 681–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulushev, D.A.; Zacharska, M.; Lisitsyn, A.S.; Podyacheva, O.Y.; Hage, F.S.; Ramasse, Q.M.; Bangert, U.; Bulusheva, L.G. Single atoms of Pt-group metals stabilized by N-doped carbon nanofibers for efficient hydrogen production from formic acid. ACS Catal. 2016, 6, 3442–3451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Bulushev, D.A.; Ross, J.R.H. Formic acid decomposition over palladium-based catalysts doped by potassium carbonate. Catal. Today 2016, 259, 453–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bulushev, D.A.; Bulusheva, L.G. Catalysts with single metal atoms for the hydrogen production from formic acid. Catal. Rev. 2021; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulushev, D.A. Progress in catalytic hydrogen production from formic acid over supported metal complexes. Energies 2021, 14, 1334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.; Surkus, E.; Chen, F.; Pohl, M.M.; Agostini, G.; Schneider, M.; Junge, H.; Beller, M. A stable nanocobalt catalyst with highly dispersed CoNx active sites for the selective dehydrogenation of formic acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 16616–16620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Surkus, A.E.; Rabeah, J.; Anwar, M.; Dastigir, S.; Junge, H.; Brückner, A.; Beller, M. Cobalt single-atom catalysts with high stability for selective dehydrogenation of formic acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020, 59, 15849–15854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.C.; Huang, Y.J.; Xing, W.; Liu, C.P.; Liao, J.H.; Lu, T.H. High-quality hydrogen from the catalyzed decomposition of formic acid by Pd–Au/C and Pd–Ag/C. Chem. Commun. 2008, 30, 3540–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.J.; Zhou, X.C.; Yin, M.; Liu, C.P.; Xing, W. Novel PdAu@Au/C core−shell catalyst: Superior activity and selectivity in formic acid decomposition for hydrogen generation. Chem. Mater. 2010, 22, 5122–5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tedsree, K.; Li, T.; Jones, S.; Chan, C.W.A.; Yu, K.M.K.; Bagot, P.A.J.; Marquis, E.A.; Smith, G.D.; Tsang, S.C.E. Hydrogen production from formic acid decomposition at room temperature using a Ag–Pd core–shell nanocatalyst. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2011, 6, 302–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yang, F.; Wang, H.; Chen, R.; Sun, P.C.; Chen, T.H. Mg2+-assisted low temperature reduction of alloyed AuPd/C: An efficient catalyst for hydrogen generation from formic acid at room temperature. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 10887–10890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X.J.; Lu, Z.H.; Jiang, H.L.; Akita, T.; Xu, Q. Synergistic catalysis of metal–organic framework-immobilized Au–Pd nanoparticles in dehydrogenation of formic acid for chemical hydrogen storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 11822–11825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.M.; Wang, Z.L.; Gu, L.; Li, S.J.; Wang, H.L.; Zheng, W.T.; Jiang, Q. AuPd–MnOx/MOF–graphene: An efficient catalyst for hydrogen production from formic acid at room temperature. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1500107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.J.; Zhou, Y.T.; Kang, X.; Liu, D.X.; Gu, L.; Zhang, Q.H.; Yan, J.M.; Jiang, Q. A simple and effective principle for a rational design of heterogeneous catalysts for dehydrogenation of formic acid. Adv. Mater. 2019, 31, 1806781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, F.Z.; Zhu, Q.L.; Yang, X.; Zhan, W.W.; Pachfule, P.; Tsumori, N.; Xu, Q. Metal-organic framework templated porous carbon-metal oxide/reduced graphene oxide as superior support of bimetallic nanoparticles for efficient hydrogen generation from formic acid. Adv. Energy Mater. 2018, 8, 1701416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Zhu, Q.L.; Tsumori, N.; Xu, Q. Immobilizing highly catalytically active noble metal nanoparticles on reduced graphene oxide: A non-noble metal sacrificial approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Pachfule, P.; Chen, Y.; Tsumori, N.; Xu, Q. Highly efficient hydrogen generation from formic acid using a reduced graphene oxide-supported AuPd nanoparticle catalyst. Chem. Commun. 2016, 52, 4171–4174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, Z.; Kitta, M.; Tsumori, N.; Guo, W.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, J.; Zou, R.; Xu, Q. Solid-solution alloy nanoclusters of the immiscible gold-rhodium system achieved by a solid ligand-assisted approach for highly efficient catalysis. Nano Res. 2020, 13, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Yan, J.M.; Ping, Y.; Wang, H.L.; Zheng, W.T.; Jiang, Q. An efficient CoAuPd/C catalyst for hydrogen generation from formic acid at room temperature. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 4406–4409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.L.; Ping, Y.; Yan, J.M.; Wang, H.L.; Jiang, Q. Hydrogen generation from formic acid decomposition at room temperature using a NiAuPd alloy nanocatalyst. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 4850–4856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yurderi, M.; Bulut, A.; Zahmakiran, M.; Kaya, M. Carbon supported trimetallic PdNiAg nanoparticles as highly active, selective and reusable catalyst in the formic acid decomposition. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2014, 160–161, 514–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Luo, W.; Cheng, G. Monodisperse CoAgPd nanoparticles assembled on graphene for efficient hydrogen generation from formic acid at room temperature. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2016, 41, 439–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Liang, B.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, T. Design strategies of highly selective nickel catalysts for H2 production via hydrous hydrazine decomposition: A review. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2018, 5, 356–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhang, A.; Yao, Q.; Lu, Z.H. Recent progress on catalysts for hydrogen evolution from decomposition of hydrous hydrazine. Acta Chim. Sin. 2021, 79, 885–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Zhang, X.B.; Xu, Q. Room-temperature hydrogen generation from hydrous hydrazine for chemical hydrogen storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 9894–9895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, A.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Delgado, J.J.; Zhang, T. A noble-metal-free catalyst derived from Ni-Al hydrotalcite for hydrogen generation from N2H4·H2O decomposition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 6191–6194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, L.; Liang, B.; Li, L.; Yang, X.; Huang, Y.; Wang, A.; Wang, X.; Zhang, T. Cerium-oxide-modified nickel as a non-noble metal catalyst for selective decomposition of hydrous hydrazine to hydrogen. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 1623–1628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Varma, A. Hydrogen generation from hydrous hydrazine over Ni/CeO2 catalysts prepared by solution combustion synthesis. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2018, 220, 409–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Wu, L.; Jia, A.; Li, X.; Shi, Z.; Duan, M.; Wang, Y. Ni nanoparticles encapsulated in the channel of titanate nanotubes: Efficient noble-metal-free catalysts for selective hydrogen generation from hydrous hydrazine. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 332, 637–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Yao, Q.; Feng, G.; Zou, H.; Lu, Z.H. Nickel-ceria nanowires embedded in microporous silica: Controllable synthesis, formation mechanism, and catalytic applications. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 59, 5781–5790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Xu, Q. Complete conversion of hydrous hydrazine to hydrogen at room temperature for chemical hydrogen storage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 18032–18033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Yadav, M.; Aranishi, K.; Xu, Q. Temperature-induced selectivity enhancement in hydrogen generation from Rh-Ni nanoparticle-catalyzed decomposition of hydrous hydrazine. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2012, 37, 18915–18919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Xu, Q. Bimetallic Ni-Pt nanocatalysts for selective decomposition of hydrazine in aqueous solution to hydrogen at room temperature for chemical hydrogen storage. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 6148–6152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Xu, Q. Highly-dispersed surfactant-free bimetallic Ni–Pt nanoparticles as high-performance catalyst for hydrogen generation from hydrous hydrazine. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 9128–9134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Yang, X.; Xu, Q. Ultrafine bimetallic Pt–Ni nanoparticles immobilized on 3-dimensional N-doped graphene networks: A highly efficient catalyst for dehydrogenation of hydrous hydrazine. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 112–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, F.Z.; Yang, X.; Xu, Q. Ultrafine bimetallic Pt–Ni nanoparticles achieved by metal-organic framework templated zirconia/porous carbon/reduced graphene oxide: Remarkable catalytic activity in dehydrogenation of hydrous hydrazine. Small Methods 2020, 4, 1900707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, H.; Zhang, S.; Hong, X.; Yao, Q.; Luo, Y.; Lu, Z.H. Immobilization of Ni-Pt nanoparticles on MIL-101/rGO composite for hydrogen evolution from hydrous hydrazine and hydrazine borane. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 835, 155426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, F.; Zou, H.; Yao, Q.; Huang, B.; Lu, Z.H. Monodispersed bimetallic nanoparticles anchored on TiO2-decorated titanium carbide MXene for efficient hydrogen production from hydrazine in aqueous solution. Renew. Energy 2020, 155, 1293–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, Y.P.; Shi, Q.; Zhou, L.L.; Chen, M.H.; Chen, C.; Tang, P.P.; Walker, G.S.; Wang, P. NiPt nanoparticles anchored onto hierarchical nanoporous N-doped carbon as an efficient catalyst for hydrogen generation from hydrazine monohydrate. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2020, 12, 18617–18624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Liu, C.; Du, C.; Cai, P.; Cheng, G.; Luo, W. Nitrogen-doped graphene hydrogel-supported NiPt-CeOx nanocomposites and their superior catalysis for hydrogen generation from hydrazine at room temperature. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 2856–2865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.K.; Iizuka, Y.; Xu, Q. Nickel-palladium nanoparticle catalyzed hydrogen generation from hydrous hydrazine for chemical hydrogen storage. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2011, 36, 11794–11801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Yao, Q.; Huang, M.; Du, H.; Lu, Z.H. Bimetallic NiIr nanoparticles supported on lanthanum oxy-carbonate as highly efficient catalysts for hydrogen evolution from hydrazine borane and hydrazine. Inorg. Chem. Front. 2019, 6, 2271–2278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song-Il, O.; Yan, J.M.; Wang, H.L.; Wang, Z.L.; Jiang, Q. High catalytic kinetic performance of amorphous CoPt NPs induced on CeOx for H2 generation from hydrous hydrazine. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2014, 39, 3755–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Yao, Q.; Qing, S.; Lu, Z.H. La(OH)3 nanosheet-supported CoPt nanoparticles: A highly efficient and magnetically recyclable catalyst for hydrogen production from hydrazine in aqueous solution. J. Mater. Chem. A 2019, 7, 9903–9911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, W.; Wen, Y.; Gu, L.; Zhang, Y. Rh-Ni-B Nanoparticles as Highly Efficient Catalysts for Hydrogen Generation from Hydrous Hydrazine. Adv. Energy Mater. 2015, 5, 1401879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Tan, S.; Cai, P.; Luo, W.; Cheng, G. A RhNiP/rGO hybrid for efficient catalytic hydrogen generation from an alkaline solution of hydrazine. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 14572–14576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Yu, J.; Bie, H.; Hao, Z. Highly efficient hydrogen generation from hydrous hydrazine using a reduced graphene oxide-supported NiPtP nanoparticle catalyst. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 690, 783–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zou, H.; Yao, Q.; Luo, M.; Li, X.; Lu, Z.H. Cr2O3-modified NiFe nanoparticles as a noble-metal-free catalyst for complete dehydrogenation of hydrazine in aqueous solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 501, 144247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W.; Guo, H.; Varma, A. Noble-metal-free NiCu/CeO2 catalysts for H2 generation from hydrous hydrazine. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2019, 249, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Wen, M.; Lin, X.; Wu, Q.; Gu, C.; Chen, H. A NiCo/NiO–CoOx ultrathin layered catalyst with strong basic sites for high-performance H2 generation from hydrous hydrazine. J. Mater. Chem. A 2016, 4, 6595–6602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, M.; Xu, Q. A high-performance hydrogen generation system: Transition metal-catalyzed dissociation and hydrolysis of ammonia–borane. J. Power Sources 2006, 156, 190–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aijaz, A.; Karkamkar, A.; Choi, Y.J.; Tsumori, N.; Roennebro, E.; Autrey, T.; Shioyama, H.; Xu, Q. Immobilizing highly catalytically active Pt nanoparticles inside the pores of metal–organic framework: A double solvents approach. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 13926–13929. [Google Scholar]

- Du, C.; Ao, Q.; Cao, N.; Yang, L.; Luo, W.; Cheng, G. Facile synthesis of monodisperse ruthenium nanoparticles supported on graphene for hydrogen generation from hydrolysis of ammonia borane. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2015, 40, 6180–6187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Ji, J.; Duan, X.; Qian, G.; Li, P.; Zhou, X.; Chen, D.; Yuan, W. Unique reactivity in Pt/CNT catalyzed hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia borane. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 2142–2144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Q.; Lu, Z.H.; Jia, Y.; Chen, X.; Liu, X. In situ facile synthesis of Rh nanoparticles supported on carbon nanotubes as highly active catalysts for H2 generation from NH3BH3 hydrolysis. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2015, 40, 2207–2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, X.; Kitta, M.; Xu, Q. Monodispersed Pt nanoparticles on reduced graphene oxide by a non-noble metal sacrificial approach for hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia borane. Nano Res. 2017, 10, 3811–3816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pachfule, P.; Yang, X.; Zhu, Q.L.; Tsumori, N.; Uchida, T.; Xu, Q. From Ru nanoparticle-encapsulated metal–organic frameworks to highly catalytically active Cu/Ru nanoparticle-embedded porous carbon. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 4835–4841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.Y.; Kochovski, Z.; Lee, H.C.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Sun, J.K.; Yuan, J. Ionic organic cage-encapsulating phase-transferable metal clusters. Chem. Sci. 2019, 10, 1450–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Chen, Z.; Li, M.; Zhou, X.; Lu, H. Amine-capped Co nanoparticles for highly efficient dehydrogenation of ammonia borane. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2014, 6, 13191–13200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahyari, M.; Shaabani, A. Nickel nanoparticles immobilized on three-dimensional nitrogen-doped graphene as a superb catalyst for the generation of hydrogen from the hydrolysis of ammonia borane. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 16652–16659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, D.G.; Zeng, X.L.; Chu, W.; Wang, D.; Wu, P. Magnetically recyclable hollow Co–B nanospindles as catalysts for hydrogen generation from ammonia borane. J. Mater. Sci. 2010, 45, 2862–2867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakap, M. Hydrogen generation from the hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia borane using electrolessly deposited cobalt–phosphorus as reusable and cost-effective catalyst. J. Power Sources 2014, 265, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, C.Y.; Kang, L.; Cao, S.; Chen, Y.; Lin, Z.S.; Fu, W.F. Nanostructured Ni2P as a robust catalyst for the hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia-borane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 15725–15729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Yang, Y.; Tang, Y. Effects of heat-treatment on the adhesive strength of diamond films coated on the cemented carbide substrates. J. Integr. Technol. 2017, 6, 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- Rakap, M. The highest catalytic activity in the hydrolysis of ammonia borane by poly(N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone)-protected palladium–rhodium nanoparticles for hydrogen generation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2015, 163, 129–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.W.; Lai, S.W.; Cho, S.O. Catalytic hydrogen generation from hydrolysis of ammonia borane using octahedral Au@Pt nanoparticles. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2015, 40, 16316–16322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, N.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, T.; Mayoral, A.; Li, L.; Zhou, X.; Xu, J.; Zhang, P.; Yu, J. Impregnating subnanometer metallic nanocatalysts into self-pillared zeolite nanosheets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 6905–6914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Liu, Y.; Wen, H.; Shen, R.; Mehdi, S.; Wu, X.; Liang, E.; Guo, X.; Li, B. Ensemble-boosting effect of Ru-Cu alloy on catalytic activity towards hydrogen evolution in ammonia borane hydrolysis. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2021, 287, 119960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Li, X.; Duan, H.; Zhang, H.; Jia, Q.; Zhang, S. Graphene supported Pt–Ni bimetallic nanoparticles for efficient hydrogen generation from KBH4/NH3BH3 hydrolysis. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 47, 11601–11610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.T.; Cai, Y.Y.; Ge, J.M.; Zhang, Y.N.; Gong, L.H.; Li, X.H.; Wang, K.X.; Ren, Q.Z.; Su, J.; Chen, J.S. Multifunctional Au–Co@CN nanocatalyst for highly efficient hydrolysis of ammonia borane. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 388–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Q.L.; Li, J.; Xu, Q. Immobilizing metal nanoparticles to metal–organic frameworks with size and location control for optimizing catalytic performance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 10210–10213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, Q.L.; Xu, Q. Highly active AuCo alloy nanoparticles encapsulated in the pores of metal–organic frameworks for hydrolytic dehydrogenation of ammonia borane. Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 5899–5901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, F.; Wang, C.; Wang, Q.; Martinez-Villacorta, A.M.; Escobar, A.; Chong, H.; Wang, X.; Moya, S.; Salmon, L.; Fouquet, E.; et al. Highly selective and sharp Volcano-type synergistic Ni2Pt@ZIF-8-catalyzed hydrogen evolution from ammonia borane hydrolysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 10034–10042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, Y.; Qin, X.; Li, A.; Deng, Y.; Lin, L.; Zhang, M.; Yu, Q.; Li, S.; Peng, M.; Xu, Y.; et al. Maximizing the synergistic effect of CoNi catalyst on α-MoC for robust hydrogen production. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143, 628–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.B.; Kang, X.D.; Wang, P. Ruthenium nanoparticles immobilized in montmorillonite used as catalyst for methanolysis of ammonia borane. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2010, 35, 10317–10323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J.K.; Zhan, W.W.; Akita, T.; Xu, Q. Toward homogenization of heterogeneous metal nanoparticle catalysts with enhanced catalytic performance: Soluble porous organic cage as a stabilizer and homogenizer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 7063–7066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Sun, J.K.; Kitta, M.; Pang, H.; Xu, Q. Encapsulating highly catalytically active metal nanoclusters inside porous organic cages. Nat. Catal. 2018, 1, 214–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, L.; Liu, H.; Kurihara, T.; Horike, S.; Xu, Q. Encapsulating ultrastable metal nanoparticles within reticular Schiff base nanospaces for enhanced catalytic performance. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2021, 2, 100289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, W.; Zhou, J.; Kochovski, Z.; Miao, H.; Gao, Z.; Sun, J.; Yuan, J. Ionic organic cage-encapsulated metal clusters for switchable catalysis. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2021, 2, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, L.; Zhang, S.; Yang, X.; Zhuang, Q.; Sun, J.K. Toward the controlled synthesis of highly dispersed metal clusters enabled by downsizing crystalline porous organic cage supports. Small Methods 2022, 6, 2200591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, X.; Bulushev, D.A.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Q. New Liquid Chemical Hydrogen Storage Technology. Energies 2022, 15, 6360. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/en15176360

Yang X, Bulushev DA, Yang J, Zhang Q. New Liquid Chemical Hydrogen Storage Technology. Energies. 2022; 15(17):6360. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/en15176360

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Xinchun, Dmitri A. Bulushev, Jun Yang, and Quan Zhang. 2022. "New Liquid Chemical Hydrogen Storage Technology" Energies 15, no. 17: 6360. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/en15176360