Mechanisms of Multidrug Resistance in Cancer Chemotherapy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

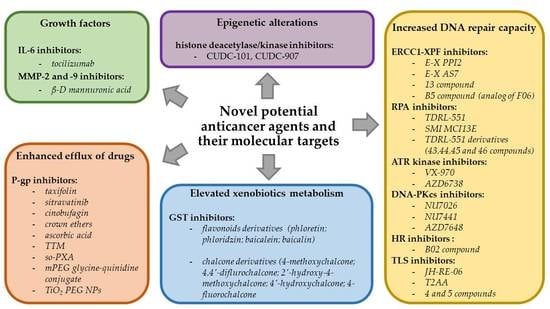

2. Types of Chemotherapeutics

3. The Problem of Drug Resistance in Cancer Chemotherapy

3.1. Enhanced Efflux of Drugs

3.2. Genetic Factors

3.2.1. Gene Mutations

3.2.2. Amplifications

3.2.3. Epigenetic Alterations

3.3. Growth Factors

3.4. Increased DNA Repair Capacity

3.5. Elevated Metabolism of Xenobiotics

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ABC | ATP-binding cassette |

| ATR | Ataxia telangiectasia and Rad3-related protein |

| 5-FU | 5-Fluorouracil |

| BCRP | Human breast cancer resistance protein |

| BBB | Blood–brain barrier |

| BRCA | Breast cancer gene |

| CAF | Chromatin assembly factor-1 |

| CD24 | Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked cell surface glycoprotein gene |

| CDK 4/6 | Cyclin-dependent kinase 4/6 |

| CML | Chronic myeloid leukemia |

| CYP | Cytochrome |

| DDR | DNA-damage response |

| DDRNAs | DNA damage response RNAs |

| decitabine; DAC | 5-Aza-2′-deoxycytidine |

| DNA-PKc | DNA-dependent protein kinase |

| DOX | Doxorubicin |

| DPDs | Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenases |

| DSB | Double-strand break |

| ECM | Extracellular matrix |

| EOC | Epithelial ovarian cancer |

| FBW7 | F-box and WD repeat domain-containing 7 protein |

| FBX8 | F-box only protein 8 |

| FDA | U.S. Food and Drug Administration |

| FEN-1 | Flap structure-specific endonuclease 1 |

| FGF | Fibroblast growth factor |

| GSAO | 4-(N-(S-glutathionylacetyl)amino)phenylarsonous acid |

| GSH | Glutathione |

| GSTs | Glutathione-S-transferases |

| HER2 | Human epidermal growth factor receptor-2 gene |

| hMLH1 | Human MutL homolog 1 gene |

| HR | Homologous recombination |

| IC50 | Half-maximum inhibitory concentration |

| ICLs | Interstrand DNA cross-links |

| iDNMT | DNA methylation inhibitor |

| iHDAC | Histone deacetylase inhibitor |

| iso-PXA | Iso-pencillixanthone A |

| LQTS | Long QT syndrome |

| MAPK | Mitogen-activated protein kinase |

| Mcl-1 | Induced myeloid leukemia cell differentiation protein |

| MDR | Multidrug resistance |

| MMP | Matrix metalloproteinase |

| MMR | Mismatch repair |

| mPEG | Methoxypolyethylene glycol |

| NER | Nucleotide excision repair |

| NHEJ | Nonhomologous end joining pathway |

| NSCLC | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| PARP | Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase protein |

| PCNA | Lys-164-mono-ubiquitinated proliferating cell nuclear antigen |

| P-gp; ABCB1 | P-glycoprotein; ATP-binding cassette subfamily B member 1 |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RPA | Replication protein A |

| RTK | Receptor tyrosine kinase |

| SCF | SKP1-CUL1-F-box |

| SCLC | Small cell lung cancer |

| SNP | Single nucleotide polymorphism |

| ssDNA | Single-strand DNA |

| T2AA | T2 amino alcohol |

| TAM | Tumor-associated macrophage |

| TCGA | The Cancer Genome Atlas |

| TiO2 PEG NP | Polyethylene glycol-modified titanium dioxide nanoparticle |

| TLS | Translesion synthesis |

| TPMTs | Thiopurine methyltransferases |

| TRAIL | Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand |

| TTM | Tometodione M |

| UGTs | Uridine diphospho-glucuronosyltransferases |

| VCR | Vincristine |

| VEGF-A | Vascular endothelial growth factor A |

| γGTs | Gamma-glutamyl transferases |

References

- Global Burden of Disease Cancer Collaboration; Fitzmaurice, C.; Allen, C.; Barber, R.M.; Barregard, L.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Brenner, H.; Dicker, D.J.; Chimed-Orchir, O.; Dandona, R.; et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 32 cancer groups, 1990 to 2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 524–548. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- WHO. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer (accessed on 12 September 2018).

- Kikuchi, H.; Yuan, B.; Hu, X.; Okazaki, M. Chemopreventive and anticancer activity of flavonoids and its possibility for clinical use by combining with conventional chemotherapeutic agents. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2019, 9, 1517–1535. [Google Scholar]

- Lichota, A.; Gwozdzinski, K. Anticancer Activity of Natural Compounds from Plant and Marine Environment. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Marchi, E.; O’Connor, O.A. Safety and efficacy of pralatrexate in the treatment of patients with relapsed or refractory peripheral T-cell lymphoma. Ther. Adv. Hematol. 2012, 3, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, X.; Li, L.; Ren, Y.; Xue, H.; Liu, H.; Wen, S.; Chen, J. Synthesis of N-Carbonyl Acridanes as Highly Potent Inhibitors of Tubulin Polymerization via One-Pot Copper-Catalyzed Dual Arylation of Nitriles with Cyclic Diphenyl Iodoniums. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2020, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, T.; Bhushan, V.; Sochat, M.; Chavda, Y. First Aid for the USMLE Step 1, 1st ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 416–419. [Google Scholar]

- Nussbaumer, S.; Bonnabry, P.; Veuthey, J.L.; Fleury-Souverain, S. Analysis of anticancer drugs: A review. Talanta 2011, 85, 2265–2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luqmani, Y.A. Mechanisms of drug resistance in cancer chemotherapy. Med. Princ. Pract. 2005, 14, 35–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onizuka, K.; Hazemi, M.E.; Sato, N.; Tsuji, G.; Ishikawa, S.; Ozawa, M.; Tanno, K.; Yamada, K.; Nagatsugi, F. Reactive OFF-ON type alkylating agents for higher-ordered structures of nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 6578–6589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Infante Lara, L.; Fenner, S.; Ratcliffe, S.; Isidro-Llobet, A.; Hann, M.; Bax, B.; Osheroff, N. Coupling the core of the anticancer drug etoposide to an oligonucleotide induces topoisomerase II-mediated cleavage at specific DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 2218–2233. [Google Scholar]

- Bax, B.D.; Murshudov, G.; Maxwell, A.; Germe, T. DNA Topoisomerase Inhibitors:Trapping a DNA-Cleaving Machine in Motion. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 3427–3449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Q.; Yang, Z.; Nie, Y.; Shi, Y.; Fan, D. Multi-drug resistance in cancer chemotherapeutics: Mechanisms and lab approaches. Cancer Lett. 2014, 347, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Seebacher, N.; Shi, H.; Kan, Q.; Duan, Z. Novel strategies to prevent the development of multidrug resistance (MDR) in cancer. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 84559–84571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wang, X.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X. Drug resistance and combating drug resistance in cancer. Cancer Drug Resist. 2019, 2, 141–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dallavalle, S.; Dobričić, V.; Lazzarato, L.; Gazzano, E.; Machuqueiro, M.; Pajeva, I.; Tsakovska, I.; Zidar, N.; Fruttero, R. Improvement of conventional anti-cancer drugs as new tools against multidrug resistant tumors. Drug Resist. Updat. 2020, 50, 100682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mesci, S.; Marakli, S.; Yazgan, B.; Yıldırım, T. The effect of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters in human cancers. Int. J. Sci. Lett. 2019, 1, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.P.; Hsiao, S.H.; Huang, Y.H.; Hung, L.C.; Yu, Y.J.; Chang, Y.T.; Hung, T.H.; Wu, Y.S. Sitravatinib Sensitizes ABCB1- and ABCG2-Overexpressing Multidrug-Resistant Cancer Cells to Chemotherapeutic Drugs. Cancers 2020, 12, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zu, Y.; Yang, Z.; Tang, S.; Han, Y.; Ma, J. Effects of P-glycoprotein and its inhibitors on apoptosis in K562 cells. Molecules 2014, 19, 13061–13075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvar, S. The role of ABC transporters in anticancer drug transport. Turk. J. Biol. 2014, 38, 800–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagas, J.S.; Fan, L.; Wagenaar, E.; Vlaming, M.L.; van Tellingen, O.; Beijnen, J.H.; Schinkel, A.H. P-glycoprotein (P-gp/Abcb1), Abcc2, and Abcc3 determine the pharmacokinetics of etoposide. Clin. Cancer Res. 2010, 16, 130–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lal, S.; Wong, Z.W.; Sandanaraj, E.; Xiang, X.; Ang, P.C.; Lee, E.J.; Chowbay, B. Influence of ABCB1 and ABCG2 polymorphisms on doxorubicin disposition in Asian breast cancer patients. Cancer Sci. 2008, 99, 816–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Satake, K.; Tsukamoto, M.; Mitani, Y.; Regasini, L.O.; da Silva Bolzani, V.; Efferth, T.; Nakagawa, H. Human ABCB1 confers cells resistance to cytotoxic guanidine alkaloids from Pterogyne nitens. Biomed. Mater. Eng. 2015, 25, 249–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vaidyanathan, A.; Sawers, L.; Gannon, A.L.; Chakravarty, P.; Scott, A.L.; Bray, S.E.; Ferguson, M.J.; Smith, G. ABCB1 (MDR1) induction defines a common resistance mechanism in paclitaxel- and olaparib-resistant ovarian cancer cells. Br. J. Cancer 2016, 115, 431–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Souza, P.S.; Madigan, J.P.; Gillet, J.P.; Kapoor, K.; Ambudkar, S.V.; Maia, R.C.; Gottesman, M.M.; Fung, K.L. Expression of the multidrug transporter P-glycoprotein is inversely related to that of apoptosis-associated endogenous TRAIL. Exp. Cell Res. 2015, 336, 318–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Galski, H.; Oved-Gelber, T.; Simanovsky, M.; Lazarovici, P.; Gottesman, M.M.; Nagler, A. P-glycoprotein-dependent resistance of cancer cells toward the extrinsic TRAIL apoptosis signaling pathway. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013, 86, 584–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Nanayakkara, A.K.; Follit, C.A.; Chen, G.; Williams, N.S.; Vogel, P.D.; Wise, J.G. Targeted inhibitors of P-glycoprotein increase chemotherapeutic-induced mortality of multidrug resistant tumor cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Guberović, I.; Marjanović, M.; Mioč, M.; Ester, K.; Martin-Kleiner, I.; Šumanovac Ramljak, T.; Mlinarić-Majerski, K.; Kralj, M. Crown ethers reverse P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance in cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, L.; Ma, Z.; Tian, L.; Liu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Chen, Q.; Li, Y.; Ma, E. Ascorbate promotes the cellular accumulation of doxorubicin and reverses the multidrug resistance in breast cancer cells by inducing ROS-dependent ATP depletion. Free Radic. Res. 2019, 53, 758–767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, X.W.; Xia, Y.Z.; Zhang, Y.L.; Luo, J.G.; Han, C.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, C.; Yang, C.; Kong, L.Y. Tomentodione M sensitizes multidrug resistant cancer cells by decreasing P-glycoprotein via inhibition of p38 MAPK signaling. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 101965–101983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuan, Z.; Shi, X.; Qiu, Y.; Jia, T.; Yuan, X.; Zou, Y.; Liu, C.; Yu, H.; Yuan, Y.; He, X.; et al. Reversal of P-gp-mediated multidrug resistance in colon cancer by cinobufagin. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 1815–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, L.; Xin, L.; Cheng, M.; Wang, S.; Zheng, Q.; Liu, Q. Iso-pencillixanthone A from a marine-derived fungus reverses multidrug resistance in cervical cancer cells through down-regulating P-gp and re-activating apoptosis. RSC Adv. 2018, 8, 41192–41206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, H.J.; Chung, Y.L.; Li, C.Y.; Chang, Y.T.; Wang, C.C.N.; Lee, H.Y.; Lin, H.Y.; Hung, C.C. Taxifolin Resensitizes Multidrug Resistance Cancer Cells via Uncompetitive Inhibition of P-Glycoprotein Function. Molecules 2018, 23, 3055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Snyder, S.; Murundi, S.; Crawford, L.; Putnam, D. Enabling P-glycoprotein inhibition in multidrug resistant cancer through the reverse targeting of a quinidine-PEG conjugate. J. Controlled Release. 2020, 317, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salama, B.; El-Sherbini, E.S.; El-Sayed, G.; El-Adl, M.; Kanehira, K.; Taniguchi, A. The Effects of TiO(2) Nanoparticles on Cisplatin Cytotoxicity in Cancer Cell Lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Duesberg, P.; Stindl, R.; Hehlmann, R. Explaining the high mutation rates of cancer cells to drug and multidrug resistance by chromosome re-assortments that are catalyzed by aneuploidy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 14295–14300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Duesberg, P.; Stindl, R.; Hehlmann, R. Origin of multidrug resistance in cells with and without multidrug resistance genes: Chromosome re-assortments catalyzed by aneuploidy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2001, 98, 11283–11288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mantovani, F.; Collavin, L.; Del Sal, G. Mutant p53 as a guardian of the cancer cell. Cell Death Differ. 2019, 26, 199–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandrasekhar, C.; Kumar, P.S.; Venkata, P.; Sarma, G.K. Novel mutations in the kinase domain of BCR-ABL gene causing imatinib resistance in chronic myeloid leukemia patients. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, G.; McMullan, R.; Robson, N.; McGimpsey, J.; Catherwood, M.; McMullin, M.F. Response to Imatinib therapy is inferior for e13a2 BCR-ABL1 transcript type in comparison to e14a2 transcript type in chronic myeloid leukaemia. BMC Hematol. 2019, 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shih, Y.T.; Cortes, J.E.; Kantarjian, H.M. Treatment value of second-generation BCR-ABL1 tyrosine kinase inhibitors compared with imatinib to achieve treatment-free remission in patients with chronic myeloid leukaemia: A modelling study. Lancet Haematol. 2019, 6, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos, S.M. Aromatase inhibitors for breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Oncologist 2004, 9, 126–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzenellenbogen, J.A.; Mayne, C.G.; Katzenellenbogen, B.S.; Greene, G.L.; Chandarlapaty, S. Structural Underpinnings of Estrogen Receptor Mutations in Endocrine Therapy Resistance. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2018, 18, 377–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansoori, B.; Mohammadi, A.; Davudian, S.; Shirjang, S.; Baradaran, B. The Different Mechanisms of Cancer Drug Resistance: A Brief Review. Adv. Pharm. Bull. 2017, 7, 339–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Zheng, P.; Liu, Y. Amplification of the CD24 Gene Is an Independent Predictor for Poor Prognosis of Breast Cancer. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fromm, M.F.; Kauffmann, H.M.; Fritz, P.; Burk, O.; Kroemer, H.K.; Warzok, R.W.; Eichelbaum, M.; Siegmund, W.; Schrenk, D. The effect of rifampin treatment on intestinal expression of human MRP transporters. Am. J. Pathol. 2000, 157, 1575–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Greiner, B.; Eichelbaum, M.; Fritz, P.; Kreichgauer, H.P.; von Richter, O.; Zundler, J.; Kroemer, H.K. The role of intestinal P-glycoprotein in the interaction of digoxin and rifampin. J. Clin. Invest. 1999, 104, 147–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Genovese, I.; Ilarib, A.; Assarafc, Y.G.; Fazid, F. Not only P-glycoprotein: Amplification of the ABCB1-containing chromosome region 7q21 confers multidrug resistance upon cancer cells by coordinated overexpression of an assortment of resistance-related proteins. Drug Resist. Updat. 2017, 32, 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wahdan-Alaswad, R.; Liu, B.; Thor, A.D. Targeted lapatinib anti-HER2/ErbB2 therapy resistance in breast cancer: Opportunities to overcome a difficult problem. Cancer Drug Resist. 2020, 3, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Zhao, Z.; Shilatifard, A. Epigenetic modifications of histones in cancer. Genome Biol. 2019, 20, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, R.; Gupta, S. Epigenetic modifications in cancer. Clin. Genet. 2012, 81, 303–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mohammad, H.P.; Barbash, O.; Creasy, C.L. Targeting epigenetic modifications in cancer therapy: Erasing the roadmap to cancer. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 403–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaminskas, E.; Farrell, A.T.; Wang, Y.C.; Sridhara, R.; Pazdur, R. FDA drug approval summary: Azacitidine (5-azacytidine, Vidaza) for injectable suspension. Oncologist 2005, 10, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, P.F.; Zhou, J.D.; Yao, D.M.; Ma, J.C.; Wen, X.M.; Zhang, Z.H.; Lian, X.Y.; Xu, Z.J.; Qian, J.; Lin, J. Efficacy and safety of decitabine in treatment of elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 41498–41507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Goey, A.K.L.; Sissung, T.M.; Peer, C.J.; Figg, W.D. Pharmacogenomics and histone deacetylase inhibitors. Pharmacogenomics 2016, 17, 1807–1815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Patnaik, S.; Anupriya. Drugs Targeting Epigenetic Modifications and Plausible Therapeutic Strategies Against Colorectal Cancer. Front. Genet. 2019, 10, 588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shimizu, T.; LoRusso, P.M.; Papadopoulos, K.P.; Patnaik, A.; Beeram, M.; Smith, L.S.; Rasco, D.W.; Mays, T.A.; Chambers, G.; Ma, A.; et al. Phase I first-in-human study of CUDC-101, a multitargeted inhibitor of HDACs, EGFR, and HER2 in patients with advanced solid tumors. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014, 20, 5032–5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Okabe, S.; Tanaka, Y.; Moriyama, M.; Gotoh, A. Effect of dual inhibition of histone deacetylase and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase in Philadelphia chromosome-positive leukemia cells. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2020, 85, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, W.; Shen, J.; Zheng, H.; Fan, W. The role and mechanisms of action of microRNAs in cancer drug resistance. J. Clin. Epigenet. 2019, 11, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Luo, X.; Wu, Y.; Xia, D.; Chen, W.; Fang, Z.; Deng, J.; Hao, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhang, T.; et al. MicroRNA-34a Attenuates Paclitaxel Resistance in Prostate Cancer Cells via Direct Suppression of JAG1/Notch1 Axis. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 50, 261–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, H.M.; Nikolic, I.; Yang, J.; Castillo, L.; Deng, N.; Chan, C.L.; Yeung, N.K.; Dodson, E.; Elsworth, B.; Spielman, C.; et al. MicroRNAs as potential therapeutics to enhance chemosensitivity in advanced prostate cancer. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 7820. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W.; Zhao, L.; Wei, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Wang, F.; Sun, G.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Y. MicroRNA-320a promotes 5-FU resistance in human pancreatic cancer cells. Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 27641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Chitkara, D.; Kumar, V.; Behrman, S.W.; Mahato, R.I. miRNA profiling in pancreatic cancer and restoration of chemosensitivity. Cancer Lett. 2013, 334, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- To, K.K.; Leung, W.W.; Ng, S.S. Exploiting a novel miR-519c-HuR-ABCG2 regulatory pathway to overcome chemoresistance in colorectal cancer. Exp. Cell Res. 2015, 338, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evert, J.; Pathak, S.; Sun, X.F.; Zhang, H. A Study on Effect of Oxaliplatin in MicroRNA Expression in Human Colon Cancer. J. Cancer 2018, 9, 2046–2053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kim, S.A.; Kim, I.; Yoon, S.K.; Lee, E.K.; Kuh, H.J. Indirect modulation of sensitivity to 5-fluorouracil by microRNA-96 in human colorectal cancer cells. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2015, 38, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Song, Y.; Mi, Y.; Jin, H.; Cao, J.; Li, H.; Han, L.; Huang, L.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; et al. MicroRNA-499a promotes the progression and chemoresistance of cervical cancer cells by targeting SOX6. Apoptosis 2020, 25 (Suppl. 3–4), 205–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.; Cui, H.; Yu, H.; Ji, Q.; Kang, L.; Han, B.; Wang, J.; Dong, Q.; Li, Y.; Yan, Z.; et al. MiR-125a promotes paclitaxel sensitivity in cervical cancer through altering STAT3 expression. Oncogenesis 2016, 5, e197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lin, F.; Wang, P.; Shen, Y.; Xie, X. Upregulation of microRNA-224 sensitizes human cervical cells SiHa to paclitaxel. Eur. J. Gynaecol. Oncol. 2015, 36, 432–436. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.; Zou, Z.; Nie, P.; Kou, X.; Wu, B.; Wang, S.; Song, Z.; He, J. Downregulation of microRNA-27b-3p enhances tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer by increasing NR5A2 and CREB1 expression. Cell Death Dis. 2016, 7, e2454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- De Mattos-Arruda, L.; Bottai, G.; Nuciforo, P.G.; Di Tommaso, L.; Giovannetti, E.; Peg, V. MicroRNA-21 links epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and inflammatory signals to confer resistance to neoadjuvant trastuzumab and chemotherapy in HER2-positive breast cancer patients. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 37269–37280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lu, L.; Ju, F.; Zhao, H.; Ma, X. MicroRNA-134 modulates resistance to doxorubicin in human breast cancer cells by downregulating ABCC1. Biotechnol. Lett. 2015, 37, 2387–2394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Jiang, J.Y.; Meng, X.N.; Xiu, Y.L.; Zong, Z.H. MiR-23b targets cyclin G1 and suppresses ovarian cancer tumorigenesis and progression. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2016, 35, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Ying, X.; Wei, K.; Lin, Z.; Cui, Y.; Ding, J.; Chen, Y.; Xu, B. MicroRNA-125b Suppresses Ovarian Cancer Progression via Suppression of the Epithelial-Mesenchymal Transition Pathway by Targeting the SET Protein. Cell Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 39, 501–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tormo, E.; Ballester, S.; Artigues, A.A.; Burgués, O.; Alonso, E.; Bermejo, B.; Menéndez, S.; Zazo, S.; Madoz-Gúrpide, J.; Rovira, A.; et al. The miRNA-449 family mediates doxorubicin resistance in triplenegative breast cancer by regulating cell cycle factors. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shang, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Z.; Feng, B.; Ren, G.; Li, K.; Zhou, L.; Sun, Y.; Li, M.; Zhou, J.; et al. miR-508-5p regulates multidrug resistance of gastric cancer by targeting ABCB1 and ZNRD1. Oncogene 2014, 33, 3267–3276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, N.; Liu, P.; Chen, Q.; Situ, H.; Xie, T.; Zhang, J.; Peng, C.; Lin, Y.; Chen, J. MicroRNA-25 regulates chemoresistance-associated autophagy in breast cancer cells, a process modulated by the natural autophagy inducer isoliquiritigenin. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 7013–7026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chen, S.; Wu, J.; Jiao, K.; Wu, Q.; Ma, J.; Chen, D.; Kang, J.; Zhao, G.; Shi, Y.; Fan, D.; et al. MicroRNA-495-3p inhibits multidrug resistance by modulating autophagy through GRP78/mTOR axis in gastric cancer. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Setrerrahmane, S.; Xu, H. Tumor-related interleukins: Old validated targets for new anti-cancer drug development. Mol. Cancer 2017, 16, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Qu, Y.; Niu, X.L.; Sun, W.J.; Zhang, X.L.; Li, L.Z. Autocrine production of interleukin-8 confers cisplatin and paclitaxel resistance in ovarian cancer cells. Cytokine 2011, 56, 365–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conze, D.; Weiss, L.; Regen, P.S.; Bhushan, A.; Weaver, D.; Johnson, P.; Rincon, M. Autocrine production of interleukin 6 causes multidrug resistance in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2001, 61, 8851–8858. [Google Scholar]

- Ham, I.H.; Oh, H.J.; Jin, H.; Bae, C.A.; Jeon, S.M.; Choi, K.; Yongon, S.; Han, S.U.; Brekken, R.A.; Lee, D.; et al. Targeting interleukin-6 as a strategy to overcome stroma-induced resistance to chemotherapy in gastric cancer. Mol. Cancer 2019, 18, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, S.; Wientjes, M.G.; Gan, Y.; Au, J.L. Fibro-blast growth factors: An epigenetic mechanism of broad-spectrum resistance to anticancer drugs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2000, 97, 8658–8663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Jimenez-Pascual, A.; Siebzehnrubl, F.A. Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor Functions in Glioblastoma. Cells 2019, 8, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Suzuki, T.; Yasuda, H.; Funaishi, K.; Arai, D.; Ishioka, K.; Ohgino, K.; Tani, T.; Hamamoto, J.; Ohashi, A.; Naoki, K.; et al. Multiple roles of extracellular fibroblast growth factors in lung cancer cells. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 46, 423–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Singh, R.K.; Kumar, S.; Gautam, P.K.; Tomar, M.S.; Verma, P.K.; Singh, S.P.; Kumar, S.; Acharya, A. Protein kinase C-α and the regulation of diverse cell responses. BioMol. Concepts 2017, 8, 143–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jena, M.K.; Janjanam, J. Role of extracellular matrix in breast cancer development: A brief update. F1000Research 2018, 7, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gentile, F.; Elmenoufy, A.H.; Ciniero, G.; Jay, D.; Karimi-Busheri, F.; Barakat, K.H.; Weinfeld, M.; West, F.G.; Tuszynski, J.A. Computer-Aided Drug Design of Small Molecule Inhibitors of the ERCC1-XPF Protein-Protein Interaction. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 2019, 95, 460–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosell, R.; Taron, M.; Ariza, A.; Barnadas, A.; Mate, J.L.; Reguart, N.; Margel, M.; Felip, E.; Mendez, P.; Garcia-Campelo, R. Molecular predictors of re-sponse to chemotherapy in lung cancer. Semin. Oncol. 2004, 31, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, C.R.R.; Silva, M.M.; Quinet, A.; Cabral-Neto, J.B.; Menck, C.F.M. DNA repair pathways and cisplatin resistance: An intimate relationship. Clinics 2018, 73, e478s. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McNeil, E.M.; Astell, K.R.; Ritchie, A.M.; Shave, S.; Houston, D.R.; Bakrania, P.; Jones, H.M.; Khurana, P.; Wallace, C.; Chapman, T.; et al. Inhibition of the ERCC1-XPF structure-specific endonuclease to overcome cancer chemoresistance. DNA Repair (Amst). 2015, 31, 19–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chapman, T.M.; Gillen, K.J.; Wallace, C.; Lee, M.T.; Bakrania, P.; Khurana, P.; Coombs, P.J.; Stennett, L.; Fox, S.; Bureau, E.A.; et al. Catechols and 3-hydroxypyridones as inhibitors of the DNA repair complex ERCC1-XPF. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2015, 25, 4097–4103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mishra, A.K.; Dormi, S.S.; Turchi, A.M.; Woods, D.S.; Turchi, J.J. Chemical inhibitor targeting the replication protein A-DNA interaction increases the efficacy of Pt-based chemotherapy in lung and ovarian cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2015, 93, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Neher, T.M.; Bodenmiller, D.; Fitch, R.W.; Jalal, S.I.; Turchi, J.J. Novel irreversible small molecule inhibitors of replication protein A display single-agent activity and synergize with cisplatin. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2011, 10, 1796–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Navnath, S.; Gavande, N.S.; VanderVere-Carozza, P.S.; Pawelczak, K.S.; Vernon, T.L.; Jordan, M.R.; Turchi, J.J. Structure-Guided Optimization of Replication Protein A (RPA)–DNA Interaction Inhibitors. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelley, M.R.; Logsdon, D.; Fishel, M.L. Targeting DNA repair pathways for cancer treatment: What’s new? Future Oncol. 2014, 10, 1215–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Helleday, T.; Petermann, E.; Lundin, C.; Hodgson, B.; Sharma, R.A. DNA repair pathways as targets for cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2008, 8, 193–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, A.B.; Newsome, D.; Wang, Y.; Boucher, D.M.; Eustace, B.; Gu, Y.; Hare, B.; Johnson, M.A.; Milton, S.; Murphy, C.E.; et al. Potentiation of tumor responses to DNA damaging therapy by the selective ATR inhibitor VX-970. Oncotarget 2014, 5, 5674–5685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vendetti, F.P.; Lau, A.; Schamus, S.; Conrads, T.P.; O’Connor, M.J.; Bakkenist, C.J. The orally active and bioavailable ATR kinase inhibitor AZD6738 potentiates the anti-tumor effects of cisplatin to resolve ATM-deficient nonsmall cell lung cancer in vivo. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 44289–44305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Albarakati, N.; Abdel-Fatah, T.M.; Doherty, R.; Russell, R.; Agarwal, D.; Moseley, P.; Perry, C.; Arora, A.; Alsubhi, N.; Seedhouse, C.; et al. Targeting BRCA1-BER deficient breast cancer by ATM or DNA-PKcs blockade either alone or in combination with cisplatin for personalized therapy. Mol. Oncol. 2015, 9, 204–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fok, J.H.L.; Ramos-Montoya, A.; Vazquez-Chantada, M.; Wijnhoven, P.W.G.; Follia, V.; James, N.; Farrington, P.M.; Karmokar, A.; Willis, S.E.; Cairns, J.; et al. AZD7648 is a potent and selective DNA-PK inhibitor that enhances radiation, chemotherapy and olaparib activity. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 5065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Alagpulins, D.A.; Ayyadevara, S.; Shmookler Reis, R.J. A Small-Molecule Inhibitor of RAD51 Reduces Homologous Recombination and Sensitizes Multiple Myeloma Cells to Doxorubicin. Front. Oncol. 2014, 4, 289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wojtaszek, J.L.; Chatterjee, N.; Najeeb, J.; Ramos, A.; Lee, M.; Bian, K.; Xue, J.Y.; Fenton, B.A.; Park, H.; Li, D.; et al. A Small Molecule Targeting Mutagenic Translesion Synthesis Improves Chemotherapy. Cell 2019, 178, 152–159.e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamanaka, K.; Chatterjee, N.; Hemann, M.T.; Walker, G.C. Inhibition of mutagenic translesion synthesis: A possible strategy for improving chemotherapy? PLoS Genet. 2017, 13, e1006842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Inoue, A.; Kikuchi, S.; Hishiki, A.; Shao, Y.; Heath, R.; Evison, B.J.; Actis, M.; Canman, C.E.; Hashimoto, H.; Fujii, N. A small molecule inhibitor of monoubiquitinated Proliferating Cell Nuclear Antigen (PCNA) inhibits repair of interstrand DNA cross-link, enhances DNA double strand break, and sensitizes cancer cells to cisplatin. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 7109–7120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Sail, V.; Rizzo, A.A.; Chatterjee, N.; Dash, R.C.; Ozen, Z.; Walker, G.C.; Korzhnev, D.M.; Hadden, M.K. Identification of Small Molecule Translesion Synthesis Inhibitors That Target the Rev1-CT/RIR Protein-Protein Interaction. ACS Chem. Biol. 2017, 12, 1903–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gioia, U.; Francia, S.; Cabrini, M.; Brambillasca, S.; Michelini, F.; Jones-Weinert, C.W.; d’Adda di Fagagna, F. Pharmacological boost of DNA damage response and repair by enhanced biogenesis of DNA damage response RNAs. Sci. Rep. 2019, 239, 6460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Pathania, S.; Bhatia, R.; Baldi, A.; Singh, R.; Rawala, R.K. Drug metabolizing enzymes and their inhibitors’ role in cancer resistance. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2018, 105, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Steppi, A.; Zhou, Y.; Mao, F.; Miller, P.C.; He, M.M.; Zhao, K.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, J. Tumoral expression of drug and xenobiotic metabolizing enzymes in breast cancer patients of different ethnicities with implications to personalized medicine. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsay, E.E.; Dilda, P.J. Glutathione S-conjugates as prodrugs to target drug-resistant tumors. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Miners, J.O.; Chau, N.; Rowland, A.; Burns, K.; McKinnon, R.A.; Mackenzie, P.I.; Tucker, G.T.; Knights, K.M.; Kichenadasse, G. Inhibition of human UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes by lapatinib, pazopanib, regorafenib and sorafenib: Implications for hyperbilirubinemia. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017, 129, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osborne, M.J.; de Oliveira, L.C.; Volpon, L.; Zahreddine, A.A.; Borden, K.L.B. Overcoming drug resistance through the development of selective inhibitors of UDP-glucuronosyltransferase enzymes. J. Mol. Biol. 2019, 431, 258–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Henderson, C.; Feun, L.; Van Veldhuizen, P.; Gold, P.; Zheng, H.; Ryan, T.; Blaszkowsky, L.S.; Chen, H.; Costa, M.; et al. Phase II study of darinaparsin in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Invest. New Drugs 2010, 28, 670–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aksoy, M.; Küfrevioglu, I. Inhibition of human erythrocyte glutathione S-transferase by some flavonoid derivatives. Toxin Rev. 2017, 36, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özaslan, M.S.; Demir, Y.; Aslan, H.E.; Beydemir, Ş.; Küfrevioğlu, Ö.İ. Evaluation of chalcones as inhibitors of glutathione S-transferase. J. Biochem. Mol. Toxicol. 2018, 32, e22047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.F.; Xu, H.H.; Yan, Y.R.; Wu, P.X.; Wu, J.H.; Zhu, X.H.; Li, J.Y.; Sun, J.B.; Zhou, K.; Ren, X.L.; et al. FBX8 degrades GSTP1 through ubiquitination to suppress colorectal cancer progression. Cell Death Dis. 2019, 10, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, H.; Zhen, C.; Liu, J.; Yang, P.; Hu, L.; Shang, P. Unraveling the Potential Role of Glutathione in Multiple Forms of Cell Death in Cancer Therapy. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity 2019, 3150145, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nunes, S.C.; Serpa, J. Glutathione in Ovarian Cancer: A Double-Edged Sword. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 1882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bansal, A.; Simon, M. Glutathione metabolism in cancer progression and treatment resistance. J. Cell Biol. 2018, 217, 2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Desideri, E.; Ciccarone, F.; Ciriolo, M.R. Targeting Glutathione Metabolism: Partner in Crime in Anticancer Therapy. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ogiwara, H.; Takahashi, K.; Sasaki, M.; Kuroda, T.; Yoshida, H.; Watanabe, R.; Maruyama, A.; Makinoshima, H.; Chiwaki, F.; Sasaki, H.; et al. Targeting the Vulnerability of Glutathione Metabolism in ARID1A-Deficient Cancers. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 177–190.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, Y.S.; Lee, D.H.; Jeong, S.Y.; Park, S.H.; Oh, S.C.; Park, Y.S.; Yu, J.; Choudry, H.A.; Bartlett, D.L.; Lee, Y.J. Ferroptosis-inducing agents enhance TRAIL-induced apoptosis through upregulation of death receptor 5. J. Cell. Biochem. 2019, 120, 928–939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pan, X.; Lin, Z.; Jiang, D.; Yu, Y.; Yang, D.; Zhou, H.; Zhan, D.; Liu, S.; Peng, G.; Chen, Z.; et al. Erastin decreases radioresistance of NSCLC cells partially by inducing GPX4-mediated ferroptosis. Oncol. Lett. 2019, 17, 3001–3008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Villablanca, J.G.; Volchenboum, S.L.; Cho, H.; Kang, M.H.; Cohn, S.L.; Anderson, C.P.; Marachelian, A.; Groshen, S.; Tsao-Wei, D.; Matthay, K.K.; et al. A Phase I New Approaches to Neuroblastoma Therapy Study of Buthionine Sulfoximine and MelphalanWith Autologous Stem Cells for Recurrent/Refractory High-Risk Neuroblastoma. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2016, 63, 1349–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Catanzaro, D.; Gaude, E.; Orso, G.; Giordano, C.; Guzzo, G.; Rasola, A.; Ragazzi, E.; Caparrotta, L.; Frezza, C.; Montopoli, M. Inhibition of glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase sensitizes cisplatin-resistant cells to death. Oncotarget 2015, 6, 30102–30114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Elgendy, M.; Cirò, M.; Hosseini, A.; Weiszmann, J.; Mazzarella, L.; Ferrari, E.; Cazzoli, R.; Curigliano, G.; DeCensi, A.; Bonanni, B.; et al. Combination of Hypoglycemia and Metformin Impairs Tumor Metabolic Plasticity and Growth by Modulating the PP2A-GSK3-MCL-1 Axis. Cancer Cell 2019, 35, 798–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Cancer Type | miRNA | Chemotherapy Agent | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| prostate cancer | microRNA-34a | paclitaxel | [60] |

| microRNA-217, microRNA-181b-5p | docetaxel, cabazitaxel | [61] | |

| pancreatic cancer | microRNA-320a micro-146 | 5-FU | [62] |

| microRNA-205, microRNA-7 | gemcitabine | [63] | |

| colorectal cancer | microRNA-519c | 5-FU | [64] |

| microRNAs-384 | oxaliplatin | [65] | |

| microRNA-96 | 5-FU | [66] | |

| cervical cancer | microRNA-499a | paclitaxel | [67] |

| microRNA -125a | paclitaxel | [68] | |

| microRNA-224 | paclitaxel | [69] | |

| breast cancer | microRNA-27b-3p | tamoxifen | [70] |

| microRNA-21 | trastuzumab | [71] | |

| microRNA-134 | DOX | [72] | |

| ovarian cancer | miR-23b | paclitaxel | [73] |

| microRNA-125b | paclitaxel | [74] | |

| microRNAs-449 | DOX | [75] | |

| gastric cancer | microRNA-508-5p | VCR, adriamycin, cisplatin, 5-FU | [76] |

| microRNA-103/107 | DOX | [77] | |

| microRNA-495-3p | adriamycin, cisplatin, 5-FU, VCR | [78] |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bukowski, K.; Kciuk, M.; Kontek, R. Mechanisms of Multidrug Resistance in Cancer Chemotherapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 3233. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms21093233

Bukowski K, Kciuk M, Kontek R. Mechanisms of Multidrug Resistance in Cancer Chemotherapy. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2020; 21(9):3233. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms21093233

Chicago/Turabian StyleBukowski, Karol, Mateusz Kciuk, and Renata Kontek. 2020. "Mechanisms of Multidrug Resistance in Cancer Chemotherapy" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 21, no. 9: 3233. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/ijms21093233