Unaccompanied Minors: Worldwide Research Perspectives

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Evolution of Scientific Production

3.2. Types, Languages of Publications, and Sources

3.3. Distribution of Publications by Country

3.4. Distribution into Thematic Categories

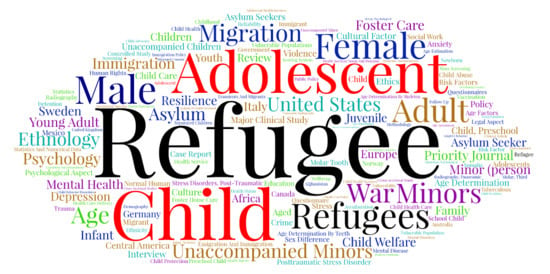

3.5. Analysis of Author Keywords and Index Keywords

3.6. Analysis of the Interconnection among Keywords: Detection of Communities

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Boswell, C. The political functions of expert knowledge: Knowledge and legitimation in European Union immigration policy. J. Eur. Public Policy 2008, 15, 471–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbulescu, R.; Grugel, J. Unaccompanied Minors, Migration Control and Human Rights at the EU’s Southern Border: The role and limits of civil society activism. Migr. Stud. 2016, 4, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parusel, B. Unaccompanied Minors in Europe: Between immigration control and the need for protection. In Security, Insecurity and Migration in Europe; Lazaridis, G., Ed.; Ashgate: Farnham, UK, 2011; pp. 139–160. [Google Scholar]

- Massey, D.S. The social and economic origins of immigration. Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 1990, 510, 60–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Androff, D. The human rights of unaccompanied minors in the USA from Central America. J. Hum. Rights Soc. Work 2016, 1, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rania, N.; Migliorini, L.; Fagnini, L. Unaccompanied migrant minors: A comparison of new Italian interventions models. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 92, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Handbook on the Optional Protocol on the Sale of Children, Child Prostitution, and Child Pornography; Innocenti Research Centre: Florence, Italy, 2009; Available online: http://www.unicefirc.org/publications/pdf/optional_protocol_eng.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2018).

- Carmel, E. European Union migration governance: Utility, security and integration. Migration and Welfare in the New Europe. Soc. Protect. Challenges Integr. 2011, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaunert, C.; Occhipinti, J.D.; Léonard, S. Introduction: Supranational governance in the Area of Freedom, Security and Justice after the Stockholm Programme. Camb. Rev. Int. Aff. 2014, 27, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaunert, C.; Léonard, S. The European Union asylum policy after the Treaty of Lisbon and the Stockholm Programme: Towards supranational governance in a common area of protection? Refugee Surv. Quart. 2012, 31, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demeny, P. Europe’s two demographic crises: The visible and the unrecognized. Pop. Dev. Rev. 2016, 42, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-Lax, V. The EU Humanitarian Border and the Securitization of Human Rights: The ‘Rescue-Through-Interdiction/Rescue-Without-Protection’ Paradigm. J. Common Mark.Stud. 2018, 56, 119–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brekke, J.P.; Brochmann, G. Stuck in transit: Secondary migration of asylum seekers in Europe, national differences, and the Dublin regulation. J. Refug. Stud. 2015, 28, 145–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, A.I.; Dornfeld, L.L. Developments of certain EU fair trial measures as part of the Stockholm Programme. Zbornik Radova 2017, 51, 865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billet, C. EC readmission agreements: A prime instrument of the external dimension of the EU’s fight against irregular immigration. An assessment after ten years of practice. Eur. J. Migr. Law 2010, 12, 45–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnár, T. EU migration law shaping international migration law in the field of expulsion of aliens–the case of the ILC draft articles. Hung. J. Legal Stud. 2017, 58, 237–260. [Google Scholar]

- Schoukens, P.; Buttiens, S. Social protection of non-removable rejected asylum-seekers in the EU: A legal assessment. Eur. J. Soc. Secur. 2017, 19, 313–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmerón-Manzano, E.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Worldwide scientific production indexed by Scopus on Labour Relations. Publications 2017, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrido-Cardenas, J.A.; Mesa-Valle, C.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Trends in plant research using molecular markers. Planta 2018, 247, 543–557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, E.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. DNA Damage Repair System in Plants: A Worldwide Research Update. Genes 2017, 8, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmeron-Manzano, E.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. The Electric Bicycle: Worldwide Research Trends. Energies 2018, 11, 1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aznar-Sánchez, J.A.; Belmonte-Ureña, L.J.; Velasco-Muñoz, J.F.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Economic analysis of sustainable water use: A review of worldwide research. J. Clean. Product. 2018, 198, 1120–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Eck, N.J.; Waltman, L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 2010, 84, 523–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla, F.M.; Gallardo, M.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Global trends in nitrate leaching research in the 1960–2017 period. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 643, 400–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EU. European Asylum Support Office. 2013. Available online: http://www.scepnetwork.org/images/21/262.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2018).

- Chavez, L.; Menjívar, C. Children without borders: A mapping of the literature on unaccompanied migrant children to the United States. Migr. Int. 2017, 5, 71–111. [Google Scholar]

- Doering-White, J. The shifting boundaries of “best interest”: Sheltering unaccompanied Central American minors in transit through Mexico. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 92, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carling, J. Migration control and migrant fatalities at the Spanish-African borders. Int. Migr. Rev. 2007, 41, 316–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, T.; McAdam, J., III. Australian Asylum Policy all at Sea: An analysis of Plaintiff M70/2011 v Minister for Immigration and Citizenship and the Australia–Malaysia Arrangement. Int. Comp. Law Quart. 2012, 61, 274–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evenhuis, M. Child-proofing asylum: Separated children and refugee decision making in Australia. Int. J. Refug. Law 2013, 25, 535–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmeling, A.; Reisinger, W.; Geserick, G.; Olze, A. Age estimation of unaccompanied minors: Part I. General considerations. Forensic Sci. Int. 2006, 159, 616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crea, T.M.; Lopez, A.; Hasson, R.G.; Evans, K.; Palleschi, C.; Underwood, D. Unaccompanied immigrant children in long term foster care: Identifying needs and best practices from a child welfare perspective. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 92, 56–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thommessen, S.A.O.T.; Corcoran, P.; Todd, B.K. Voices rarely heard: Personal construct assessments of Sub-Saharan unaccompanied asylum-seeking and refugee youth in England. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2017, 81, 293–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, J.M. La necesidad de un protocolo común en Europa sobre la detención de menores extranjeros no acompañados. Revista de Derecho Comunitario Europeo 2013, 17, 1061–1090. [Google Scholar]

- Derluyn, I.; Broekaert, E. Different perspectives on emotional and behavioural problems in unaccompanied refugee children and adolescents. Ethn. Health 2007, 12, 141–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ní Raghallaigh, M. The causes of mistrust amongst asylum seekers and refugees: Insights from research with unaccompanied asylum-seeking minors living in the Republic of Ireland. J. Refug. Stud. 2013, 27, 82–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodman, J.H. Coping with trauma and hardship among unaccompanied refugee youths from Sudan. Qual. Health Res. 2004, 14, 1177–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vervliet, M.; De Mol, J.; Broekaert, E.; Derluyn, I. ‘That I Live, that’s Because of Her’: Intersectionality as Framework for Unaccompanied Refugee Mothers. Br. J. Soc. Work 2013, 44, 2023–2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Graeve, K.; Bex, C. Caringscapes and belonging: An intersectional analysis of care relationships of unaccompanied minors in Belgium. Child. Geogr. 2017, 15, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boothby, N. Reuniting Unaccompanied Children and Families in Mozambique: An Effort to Link Networks of Community Volunteers to a National Programme. J. Soc. Dev. Africa 1993, 8, 11–22. [Google Scholar]

- Bemak, F.; Timm, J. Case study of an adolescent Cambodian refugee: A clinical, developmental and cultural perspective. Int. J. Adv. Counsell. 1994, 17, 47–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolff, P.H.; Tesfai, B.; Egasso, H.; Aradomt, T. The orphans of Eritrea: A comparison study. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 1995, 36, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukakayumba, E. Rwanda: Violence committed against women in the context of generalized armed conflict. Rech. Fem. 1995, 8, 145–154. [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, M.; Stein, A. The mental health of refugee children. Arch. Dis. Child. 2002, 87, 366–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lustig, S.L.; Kia-Keating, M.; Knight, W.G.; Geltman, P.; Ellis, H.; Kinzie, J.D.; Saxe, G.N. Review of child and adolescent refugee mental health. J. Am. Acad. Child Adol. Psychiatry 2004, 43, 24–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhabha, J.; Young, W. Not adults in miniature: Unaccompanied child asylum seekers and the new US guidelines. Int. J. Refug. Law 1999, 11, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olze, A.; Reisinger, W.; Geserick, G.; Schmeling, A. Age estimation of unaccompanied minors: Part II. Dental aspects. Forensic Sci. Int. 2006, 159, S65–S67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuzzolese, E.; Di Vella, G. Forensic dental investigations and age assessment of asylum seekers. Int. Dent. J. 2008, 58, 122–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- United Nations. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Adopted and Opened for Signature, Ratification and Accession by General Assembly Resolution 44/25 of 20 November 1989, Entry into Force 2 September 1990, in Accordance with Article 49. Available online: http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CRC.aspx (accessed on 15 September 2018).

- Kenny, M.A.; Loughry, M. Addressing the limitations of age determination for unaccompanied minors: A way forward. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 92, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thevissen, P.; Kvaal, S.I.; Dierickx, K.; Willems, G. Ethics in age estimation of unaccompanied minors. J. Forensic Odonto-Stomatol. 2012, 30, 85–102. [Google Scholar]

- Rania, N.; Migliorini, L.; Sclavo, E.; Cardinali, P.; Lotti, A. Unaccompanied migrant adolescents in the Italian context: Tailored educational interventions and acculturation stress. Child Youth Serv. 2014, 35, 292–315. [Google Scholar]

- Bravo, A.; Santos-González, I. Asylum-seeking children in Spain: Needs and intervention models. Psychosoc. Int. 2017, 26, 55–62. [Google Scholar]

| Source Title | N | Ntot | CiteScore (2017) | SJR (2017) | SNIP (2017) | Citations (2017) | % Not Cited (2017) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Work and Society | 17 | 24 | 0.22 | 0.132 | 0.18 | 50 | 45.83 |

| Children and Youth Services Review | 16 | 398 | 1.8 | 0.813 | 1.114 | 7297 | 34.17 |

| International Journal of Refugee Law | 10 | 26 | 0.63 | 0.389 | 0.748 | 453 | 61.54 |

| Child and Family Social Work | 9 | 180 | 1.66 | 0.941 | 1.38 | 1701 | 29.44 |

| Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies | 8 | 193 | 2.11 | 1.486 | 1.761 | 4267 | 26.94 |

| Journal of Refugee Studies | 8 | 29 | 1.62 | 1.197 | 1.867 | 1533 | 44.83 |

| International Journal of Legal Medicine | 7 | 237 | 2.21 | 1.21 | 1.25 | 4606 | 29.54 |

| Childhood | 6 | 40 | 1.53 | 0.894 | 1.611 | 1475 | 42.5 |

| International Migration | 6 | 93 | 1.28 | 0.887 | 1.118 | 1932 | 55.91 |

| Country | Main Keywords Used | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |

| USA | Refugees | Ethnology | Major Clinical Study |

| UK | Refugees | Asylum | Mental Health |

| Germany | Refugees | Minor (person) | Age Determination |

| Sweden | Refugees | Asylum Seeker | Immigration |

| Norway | Refugee | Depression | Mental Health |

| Italy | Age Determination | Age Determination by Teeth | Age Estimation |

| Belgium | Age Determination by Teeth | Asylum | Care |

| Spain | Detention | Inhuman or Degrading Treatment | Migration/Administrative Reform |

| Australia | Refugee | Asylum Seeker | Child Welfare |

| Canada | Child Welfare | Refugee | Asylum Seeker/Immigration Policy |

| Netherlands | Refugee | Adult | Controlled Study |

| Interest | Geographical Area | Origin/Destination |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | United States | Destination |

| 2 | Central America | Origin |

| 3 | Germany | Destination |

| 4 | Europe | Destination |

| 5 | Africa | Origin |

| 6 | Italy | Destination |

| 7 | United Kingdom | Destination |

| 8 | Afghanistan | Origin |

| 9 | Australia | Destination |

| 10 | Canada | Destination |

| 11 | Mexico | Origin |

| 12 | Norway | Destination |

| 13 | Somalia | Origin |

| Institution | Main Keywords Used | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | |

| Stockholms Universitet | Human | Sweden | Asylum Seeker/Refugee |

| Universiteit Gent | Belgium | Care | Humanitarianism/Intersectionality |

| University College Dublin | Foster Care | Asylum Seeker | Ireland/Resilience |

| New York University | Female/Male | Central America | Cultural Factor/Ethnology |

| Centers for Disease Control and Prevention | Adolescent | Human | Ethnology |

| Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin | Human | Adolescent | Refugee |

| Boston College | Child | Foster Care | Immigration/ Refugee |

| Harvard Medical School | Female/Male | Human | Refugee |

| Universitetet i Oslo | Human/Male | Refugee | Posttraumatic Stress Disorder |

| King’s College London | Adolescent/Human | Child | Refugees |

| Cluster | Colour | Keywords | Countries (Keyword) | Name | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Red | Refugee, asylum seeker, foster care, human rights, immigration | Australia, Canada, Central America, Europe, Mexico, Netherland, Sweden, the UK | Refugee–asylum seeker | 23.3 |

| 2 | Green | Refugees, psychology, psychological aspect, mental health, ethnology, depression, male, female, post-traumatic stress disorder, sex factor | Norway | Refugees–Psychology | 22.7 |

| 3 | Blue | United States, migration, education, child abuse, international migration, war, health service, vulnerability, emigration and immigration | The United States, Sudan, Africa | Emigration and immigration | 18.8 |

| 4 | Yellow | Age assessment, age determination, age estimation, grow development and aging, minors, molar tooth, third molar, legal aspect, radiography | Italy | Age determination | 18.2 |

| 5 | Purple | Asylum-seeker, heath status, paediatrics, trauma, tuberculosis, vaccination, vulnerable population | Germany | Heath care | 17 |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Salmerón-Manzano, E.; Manzano-Agugliaro, F. Unaccompanied Minors: Worldwide Research Perspectives. Publications 2019, 7, 2. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/publications7010002

Salmerón-Manzano E, Manzano-Agugliaro F. Unaccompanied Minors: Worldwide Research Perspectives. Publications. 2019; 7(1):2. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/publications7010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleSalmerón-Manzano, Esther, and Francisco Manzano-Agugliaro. 2019. "Unaccompanied Minors: Worldwide Research Perspectives" Publications 7, no. 1: 2. https://0-doi-org.brum.beds.ac.uk/10.3390/publications7010002